“People may not realize that the creation and marketing of automobiles requires a financial system.”

That was Manhattan Institute’s Diana Furchtgott-Roth writing for RealClearMarkets.com, responding to a piece from the New York Times’ Paul Krugman, “Paranoia of the Plutocrats.”

In his piece, Krugman criticizes the current credit-driven financial system: “We’re not talking captains of industry here, men who make stuff. We are, instead, talking about wheeler-dealers, men who push money around and get rich by skimming some off the top as it sloshes by. They may boast that they are job creators, the people who make the economy work, but are they really adding value? Many of us doubt it.”

But why do so many doubt the financial system adds value to our economy?

Here, Krugman is questioning something similar that we at Americans for Limited Government had when we correlated credit growth to GDP. Except in Krugman’s case he is obsessed with those who profit off of the system, whereas our focus has been one of long-term sustainability of credit-driven growth.

The trouble is not that private companies or government entities like Fannie Mae or Sallie Mae issue credit or earn profits on interest per se.

It is that when credit issuance becomes excessive, with debt growing at rates far greater than economic growth and incomes — creating artificial demand for an asset — affordability becomes an issue and bubbles will form, as was seen recently in housing.

The subsequent financial crisis and recession, then, with millions of jobs lost and flat income growth, created an environment ripe for the likes of Krugman and President Barack Obama to rip institutions that do indeed profit from credit allocation. In short, to demonize the wealthy.

Government, not profit, was the problem

But the problem never was the profit motive. Even if the financial system were completely owned and operated by the government as a public utility at no profit — a demand of the recent Occupy Wall Street movement — there is little reason to believe it would have produced a different result.

Particularly since much of the credit allocation in the last cycle was government-directed anyway via Fannie and Freddie to those with lower incomes, orders of magnitude far greater than what was created by the private sector.

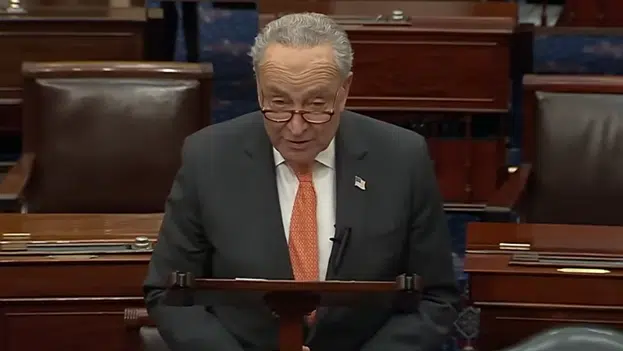

Much of the trouble could be traced to when Graham-Leach-Bliley financial reform repealing Glass-Steagall was passed in 1999. It almost did not pass due to concerns by the Clinton White House and congressional Democrats such as Senators Chuck Schumer and Chris Dodd over the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), as chronicled by the New York Times’ Stephen Labaton in 1999.

The White House “wanted the legislation to prevent any bank with an unsatisfactory record of making loans to the disadvantaged from expanding into new areas, like insurance or securities.”

When all was said and done, the final agreement provided that “no institution would be allowed to move into any new lines of business without a satisfactory lending record.”

In other words, Democrats were okay with rolling back Glass-Steagall — the banks, investment houses, and insurance companies could merge — so long as low-income lending programs would be expanded.

And with the prospect of new bank mergers on the horizon, community groups like the National Housing Institute were busy outlining plans for using the impending mergers to leverage CRA commitments from the new megabanks.

In 2000, CRA loans totaled $135 billion, according a Department of Treasury report required by Gramm-Leach-Bliley. By 2007, CRA commitments from banks totaled $4.5 trillion, according to research by American Enterprise Institute’s Edward Pinto. This facilitated the production of 26.7 million risky, non-traditional mortgages — like subprime and Alt-A.

Wall Street investment houses had their hands in this market, but it paled in comparison to Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and other federal agencies, which owned or guaranteed 70 percent of these risky loans, according to Pinto’s research.

Pinto traced the housing bubble to federal government policies to foster home ownership to low-income Americans who, it turns out, could not afford the loans they were taking out. Specifically, it was HUD that imposed so-called “affordable housing goals” on Fannie and Freddie, which rose from 30 percent in 1993 to 56 percent by 2008. Also, the FHA helped to weaken lending standards, expanding government-held loans with down payments of 3 percent or less from $7 billion 1991 to over $174 billion in 2007, $160 billion of which were held by the GSEs.

By 2008, Fannie and Freddie held $1.835 trillion in higher-risk mortgages and mortgage-backed securities: $1.646 trillion, were GSE-issued mortgage-backed securities, and $189 billion of subprime and Alt-A private mortgage-backed securities, Also, because of the implicit backing of taxpayers, Pinto notes that the GSE-issued securities were automatically granted AAA bond ratings, and the GSEs were even able to misrepresent the quality of mortgages that underlined those securities.

Such leverage was made possible by congressional passage of the GSE Act of 1992, which established Fannie and Freddie’s capital requirements. Writes Pinto, “The GSEs only needed $900 in capital behind a $200,000 mortgage they guaranteed — many of which by 2004-2007 had no borrower downpayment. In order for the private sector to compete with Fannie and Freddie, it needed to find ways to increase leverage.”

Thus excessive credit was issued by all involved parties into housing, and the rest is history.

Can the economy grow without credit?

Nonetheless, the horrendous outcome leaves a dilemma for those who defend the system against the current assault from the left.

No small part of that dilemma is that many see no other way for the economy to function and grow than through the allocation of credit. Yet, after the credit bubble we just experienced, the aftermath appears to be an economy that no longer grows, no longer creates enough work, and leaving many to question whether the system still serves the interests of the people. That disconnect may be why a candidate like Mitt Romney, a successful investor, fared so poorly in the past cycle.

In the Wealth of Nations, classical economist Adam Smith wrote on the benefits of credit allocation, which in 1776 were called “cash accounts”: “By means of those cash accounts every merchant can, without imprudence, carry on a greater trade than he otherwise could do… and give employment to a greater number of people.”

The use of bank credit, therefore, was and is a means of facilitating commerce. So far, so good.

It may be an exaggeration to suggest that cars could not be built but for credit — to follow that to its logical conclusion, but for borrowing money no innovation or progress at all would be possible — but it likely suffices to say that with credit we see more growth than otherwise would be possible.

But, Smith warned, it should not be excessive. On the issuance of credit, Smith warned banks against “issuing more paper money than what the circulation of the country could easily absorb and employ.”

This is where the issue gets thorny, for, what is excessive?

Clearly, in 2008, the financial sector via government and private companies issued far more in debt than could be easily absorbed. As a result the amount of debt being issued has slowed down drastically in the past five years. It used to grow at 8.3 percent a year in the postwar period through 2008. Since then, it’s only averaged 1.5 percent a year.

Today, there $58 trillion of credit outstanding nationwide — that is, all debts public and private — and just $11 trillion of currency, according to data compiled by the Federal Reserve. Meaning every dollar in your pocket has been already been lent about five times. That may still be more than the economy can absorb and employ, and if so, we should expect credit creation to remain subdued for the foreseeable future.

On the issue at hand, then, it is fine to defend the financial system as a practical necessity in the modern world, but for everyone’s sake it must be limited to what our economy can handle. Otherwise all of the prosperity such a system affords will continue to be the prey of class warriors like Krugman and Obama — or worse.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government