You’ve heard it a bazillion times. The end of quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve — since August 2007 it has added $3.6 trillion to its balance sheet — will mean interest rates have to rise. Because, well, they have to.

At first, there was some truth to the claim. In 2013, after the Fed said it would begin tapering its purchases, yes, there was a correction in interest rates. 10-year U.S. treasuries rose up to about 3 percent from all-time lows.

But guess what? It didn’t last.

In 2014, rates have been declining all year long, even as the Fed has been good to its word on taper and reduced its asset purchases, now down to just $15 billion a month. In the recent market panic, there was another flight to safety, which has pushed the 10-year down closer to 2 percent.

And, that market panic, in some respects, was driven by the end of quantitative easing, if reputable accounts such as the UK Telegraph’s inexhaustible financial analyst Ambrose Evans-Pritchard are to be believed.

Writing in a column titled, “One simple reason why global stock markets are reeling,” Evans-Pritchard made the case that the recent downturn all falls on the Fed: “It is no mystery why global liquidity is evaporating. Central banks have turned off the tap. They have reduced net stimulus by roughly $125billion a month since the end of last year, or $1.5 trillion annualized.”

The end of quantitative easing provoked a flight out of equities and counterintuitively into safer government bonds, which is now driving interest rates down.

Recall the Fed’s rationale for bond purchases in the first place: “to reduce the cost and increase the availability of credit for the purchase of houses, which in turn should support housing markets and foster improved conditions in financial markets more generally.”

Later, the reason for maintain the asset purchases has been, ironically, to “maintain downward pressure on longer-term interest rates.”

Turns out, the way to push rates down was to remove government support of bonds.

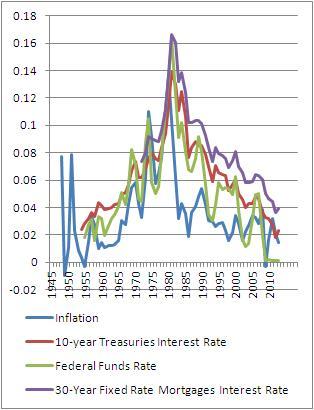

The fact is, interest rates on balance have been collapsing for 30 years, long before the days of quantitative easing.

There will undoubtedly be more corrections on the upside, but why should the overall trend stop now?

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.