“[T]he Committee decided to conclude its asset purchase program this month. The Committee is maintaining its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities and of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction. This policy, by keeping the Committee’s holdings of longer-term securities at sizable levels, should help maintain accommodative financial conditions.”

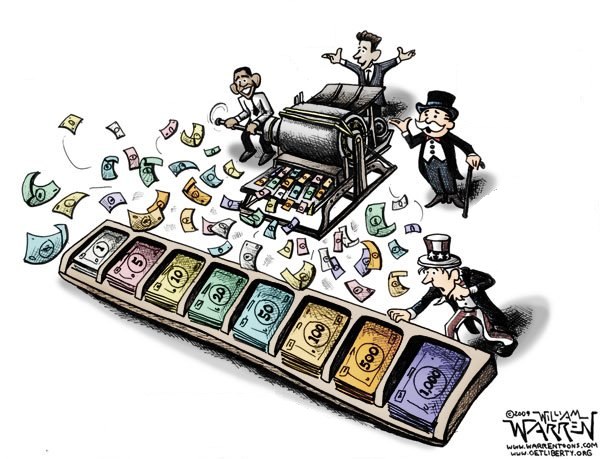

That was the Federal Reserve announcing the supposed conclusion of quantitative easing (QE), that is, its U.S. treasuries and Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSE) mortgage-backed securities purchase program that was announced in late 2008 in the middle of the financial crisis.

In the same breath, the central bank announced that there are still be tens of billions of dollars of asset repurchases every year. As mortgage principal is paid down, the Fed will continue to purchase new mortgage debt. As Treasury debt matures, it will continue to buy new Treasury debt.

Call it QE forever.

This is significant because $1 trillion of the Fed’s treasuries holdings are in 1 to 5 year maturities. So, right there, you have an average $200 billion a year, or $17 billion a month of treasuries purchased by the Fed.

As for mortgages, $1.71 trillion of its $1.715 trillion of its holdings are between 10 and 30 years’ maturity. More precise data is not offered, therefore, depending on the average maturity of the Fed’s mortgage holdings, whether the mortgages were 30-year mortgages to begin with, and even the interest rate on the loans in question, it is hard to say how much principal will be repaid annually.

For example, if one assumes they were 30 year paper, at average interest rate of 5 percent, and an average maturity of 15 years, one might expect about $50 billion of principal repayment annually from its holdings. If it’s 20 years, then that number drops to $40 billion. If it’s 25 years, down to about $30 billion.

So, since we know the Fed bought a lot more long-term mortgage paper than short-term, let’s split the difference on the long end and say principal will be repaid at about $35 billion a year. That means the Fed will be buying about $35 billion of new mortgage paper issued by the GSEs — Fannie, Freddie, and Ginnie — every year.

Guess what? That’s enough to cover about 60 percent of the $58 billion of net, new mortgages that were guaranteed by the GSEs in 2013, and more than enough to cover 100 percent of them in 2014 on account of the fact that outstanding mortgage debt guaranteed by the GSEs has actually dropped by $37 billion this year so far, according to data compiled by the Federal Reserve.

But, because the Fed’s portfolio will be maturing on an annual basis faster than it is acquiring new mortgages, by 2019, MBS purchases could be $40 billion a year. By 2024, $50 billion a year. And so forth for as long as the repurchase program continues.

So, even though the Fed holds about 35 percent of mortgages issued by the GSEs, as principal is repaid on its holdings, it still may be able to acquire a majority of net, new GSE mortgages going forward, especially if overall mortgage maturity exceeds the number of new mortgages entering the system.

Therefore, the asset purchases are not concluded. In fact, they will never be concluded. Such is the nature of open market operations.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.