You’re a slacker!

That is Heritage Foundation economist Stephen Moore’s apparent take on young people failing to enter the workforce — reminiscent of the depiction of Principal Strickland in Back to the Future — writing an op-ed in The Washington Times, “Young Americans opting out of workforce.”

In it, Moore points to declining labor participation by young people at the same time job openings are plentiful. The question is why?

“The labor-force participation rate is falling fastest among workers under 30,” Moore writes, noting “negative attitudes toward blue-collar work,” and young people graduating college without “basic” and “useful” skills.

There are plenty of jobs for “skilled and reliable mechanics, welders, engineers, electricians, plumbers, computer technicians and nurses,” says Moore, but young people are not taking those jobs. Apparently, because they don’t want to.

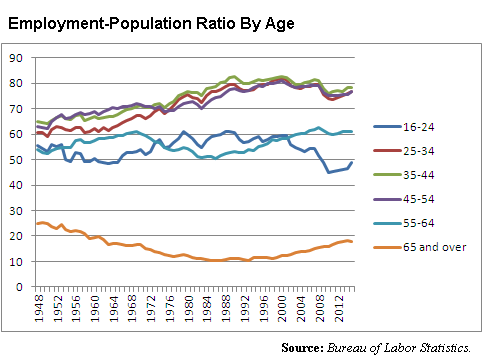

What Moore does not tell you is that the employment-population ratio for those aged 25 to 34 is as high as it was in 1986, at 76.8 percent. It peaked in 2000 at close to 82 percent and again in 2007 near 80 percent before it slumped in the Great Recession. After bottoming at 73.7 percent in December 2009 — slackers! — it has rebounded to its current level.

So, did 25 to 34 year olds become less ambitious right at the same time the worst recession since the Great Depression occurred?

No, because this followed the same trend as 35 to 44 year olds and 45 to 54 year olds. More slackers, apparently. On the margins, 25 to 34 year olds were no less likely to participate in the workforce as their older counterparts. Meaning, whatever the problem is, it is not unique to younger Americans.

Most of the drop off in young people with jobs actually occurred in the 16 to 24 year old demographic, from about a 54 percent employment-population ratio in 2007 to less than 45 percent by 2010. And not because they weren’t signing up to be mechanics or electricians.

What Moore does not mention is that this is not at all unusual for young people in the periods that follow big recessions.

The employment-population ratios of 16 to 24 year olds took by far the biggest hits in the recessions of the early 1980’s, 1991, 2001, and 2007 through 2009. The number of jobs in this age group tended to drop by about 6 percent on average for each recession, compared to about 3.5 percent for 25 to 34 year olds, and less than 2 percent for everyone else.

Why, it’s almost as if during recessions, those youngest and with the least experience are the first people to be laid off.

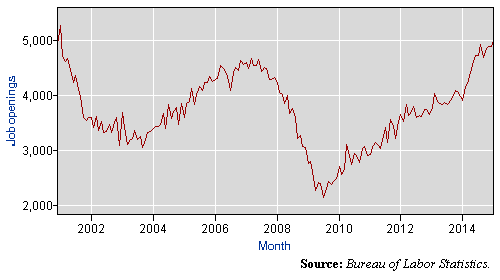

Finally, Moore cites a high demand for blue-collar labor today, but fails to mention that demand for labor is up pretty much across the board, according to data compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, which shows nearly 5 million job openings nationwide.

Moore also fails to note that the trend of job openings is cyclical. Previous peaks occurred in March 2007 at 4.66 million, and in January 2001 at 5.3 million.

All of which has nothing to do with a lack of ambition to work in blue collar jobs. If anything, the number of job openings today could be a flashing light warning of an overheating economy.

So, it might be fashionable to chide younger people for being lackadaisical — when is that not fashionable? — and yet it ignores some of the important indicators of what labor markets are really telling us right now.

Namely, that young people and everyone else have barely begun to recover from the last recession, and it looks like the whole thing is about to pop again.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.