“Except in the short run, real interest rates are determined by a wide range of economic factors, including prospects for economic growth — not by the Fed.”

That was former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, very much downplaying the extent to which the nation’s central bank “controls” interest rates in his inaugural blog post for the Brookings Institution.

Here, Bernanke is referring to the federal funds rate, which is the short-term policy rate set by the Fed. He noted that it’s the central bank’s job to set the rate: “[The Fed] has no choice but to set the short-term interest rate somewhere. So where should that be?”

Good question. Leaving aside whether the central bank ought to be setting interest rates — why can’t markets do it since they set all the other rates? — two questions emerge: 1) where should the short rate be; and 2) how much should long rates be?

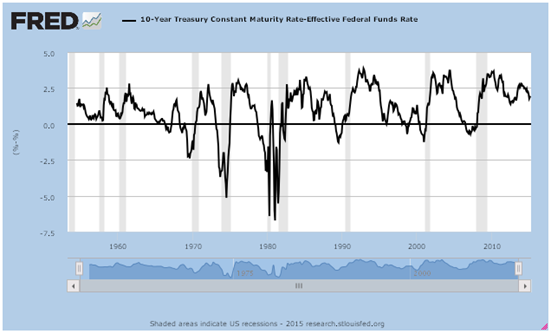

Ask anyone who knows something about the topic, and they’ll say that the short-term interest rate has to be below other longer-term interest rates. Otherwise, there might result an inverted yield curve and those are bad, since these are historically linked to recessions.

Leaving aside whether those inversions are causative in terms of recessions — aren’t recessions cyclical? — there is really no claim being made that the short rate is pushing the long rate higher. Otherwise, the yield curve might not invert at all.

So, if the Fed’s policy rate can’t push long rates higher with any effect, how can it push long rates lower? It can’t.

If anything, markets set rates principally in response to the demand for credit.

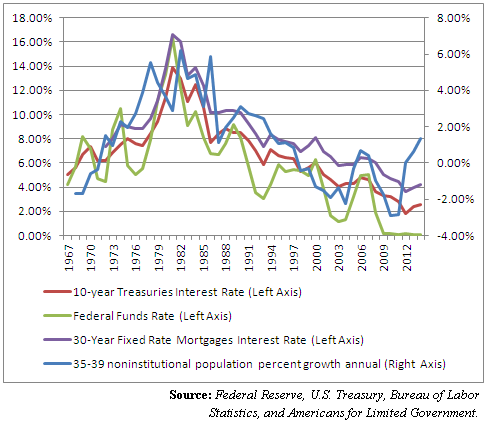

Previously, we have looked at the rate of growth of the population of 35 to 39 year olds as a proxy for the general direction interest rates tend to be headed, based on the idea that 39 years old is the median age of typical home buyers, according to the National Association of Realtors.

In this market-oriented view, as baby boomers entered the labor force and eventually started purchasing homes and engaging in more spending, it led to large demand for credit and also a lot of inflation. So interest rates responded in a market-oriented way and went up. When the population explosion slowed down, so too did rates come down.

So markets determine rates, generally speaking. Bernanke is right.

But one outlier in this analysis happens to be right now. Namely, there is a slight burst in the population of people at median home-buying age, and this might predict higher rates.

Yet, while rates were up slightly on average in 2013 and 2014, it was hardly a surge. So what else might be helping keep rates down?

Quantitative easing (QE). Since the summer of 2007 when the financial crisis began, the Fed has dramatically expanded its U.S. treasuries and mortgage-backed securities holdings by $3.4 trillion.

This, undoubtedly, created artificial demand for these instruments, which should have driven interest rates lower.

How much lower is an interesting question, but it is also unknowable.

What appears clear is that rates were likely headed lower anyway at the time of the crisis; but, right now, they might be higher but for the Fed’s actions.

Particularly since the Fed has no intention of retiring its QE holdings. As its U.S. treasuries and mortgage securities mature, the central bank plans to buy more to keep at current levels. This too will create a footprint in the marketplace that is undeniable, Bernanke’s commentary on the impact of the policy rate notwithstanding.

Besides, when the Fed announced the QE program in December 2008, it said, “This action is being taken to reduce the cost … of credit,” meaning to reduce interest rates.

So, the Fed can impact longer-term rates, but not in the way everyone thinks. Quantitative easing only began about six years ago, and how impactful it really is remains to be seen. What about the rest of the interest rate cycle over the past 60 years? What emerges is a view of the central bank that is not as powerful as we once thought. Something to consider.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.