Federal Reserve Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer let the cat out of the bag on March 23 when he told the Economic Club of New York that raising the federal funds interest rate from its near-zero levels “likely will be warranted before the end of the year.”

Fischer’s comments were immediately followed by St. Louis Federal Reserve Chairman James Bullard who suggested to the UK Telegraph’s Ambrose Evans-Pritchard that “Zero interest rates are no longer appropriate for the US economy. If we don’t start normalizing monetary policy we’ll be badly behind the curve two years from now.”

So the writing is on the wall, the Fed is ready to start hiking rates again.

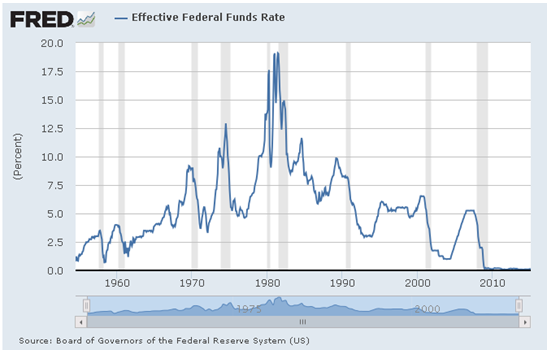

But watch out. When the central bank’s rate peaks, that usually precedes a U.S. recession, data compiled by the central bank shows.

You will notice right before recessions, the Fed tends to hike rates upward like clockwork, and then when the recession actually hits, it cuts rates. This has happened without fail in 1957-58, 1960-61, 1970-71, 1974-75, 1980, 1982-83, 1990-91, 2001-02, and 2007-09.

Are these planned recessions? In this view, the central bank’s interest rate is causative. If rates get too high, per the view, or higher than markets can withstand, credit seizes up, and this triggers a recession.

This is a common view shared by many financial observers. For example by Richard Salsman, writing for Forbes.com, “How Bernanke’s Fed triggered the Great Recession,” noting the Fed’s interest rate hikes in 2006 and 2007 that preceded the downturn.

But did the Fed really trigger the recession? Or was it the wave of foreclosures and the collapse of demand for housing following the huge-run up in home values?

Certainly, low interest rates may have contributed to the housing bubble, but overall, were buyers chasing slightly lower borrowing costs, or the expectation that housing prices would continue rising rapidly? History shows us it was the latter.

Furthermore, the Fed does not set market interest rates. Markets do.

This is a point former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke made in his inaugural blog entry for the Brookings Institution, writing, “Except in the short run, real interest rates are determined by a wide range of economic factors, including prospects for economic growth — not by the Fed.” Bernanke is right.

As an Americans for Limited Government analysis of Fed, U.S. Treasury, and Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows, markets set rates principally in response to the demand for credit.

Specifically, the rate of growth of the population of 35 to 39 year olds appears to within a certain range, predict interest rates. It is not perfect, but as a proxy it does seem to offer a guide as to the general direction interest rates tend to be headed.

Why 35 to 39 year olds? 39 years old is the median age of typical home buyers, according to the National Association of Realtors. It varies from year to year, but that age range appears to hold up over the long haul.

So, the baby boom led to a surge of home buying and other consumption in the 1970’s. This fueled not only the Great Inflation but the surge in interest rates that decade. And then in the mid-1980’s, when the population surge slowed, and then ended, credit demand subsided and inflation and interest rates came back down.

The model also shows that the temporary increase in interest rates in 2006 and 2007 coincided with the slight increase in the population of 35 to 39 year olds. And that the subsequent collapse of rates overlapped with a decrease of that population. And that as soon as that population began increasing again in 2013 and 2014, so too did rates.

And in 2015, the population of 35 to 39 year olds is set to increase yet again before it begins slowing down. One supposes interest rates will continue to follow suit, particularly if it coincides with an increase in existing home sales. So far, in January and February, existing home sales are up year over year 3.2 percent and 4.7 percent, respectively, according to the National Association of Realtors.

But in all of the historical cases, it was not the Fed that was pushing rates around. Instead, the central bank was responding to market conditions with what it views is a federal funds rate — the rate at which banks borrow — conducive to controlling inflation, or boosting economic growth, or reducing unemployment or whatever it perceives its mandate to be.

The point is, it is very common for the Fed to keep its interest rate well below that of market interest rates. And it also incredibly common that, after a while, the Fed then raises its rate to be closer to the market rates. Usually, that rate peaks right at the time a recession is about to occur.

But the Fed is not causing the recessions. Those are cyclical. The reason the central bank might be raising the rate prior to an economic contraction is so that it again has room to lower the rate afterward. Or simply to stamp out inflation.

Right now, markets are signaling higher rates in the short-term. Will the Fed follow suit?

Time will tell, but the point is, the Fed does not set market interest rates or choose when the economy enters recessions. Markets do.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.