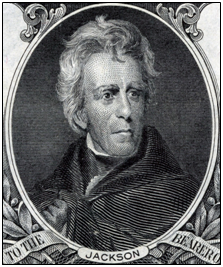

Right on it, the bill says, “Federal Reserve Note,” an institution he would have despised.

As President, when the renewal of the Second Bank of the United States’ charter passed Congress, Jackson vetoed it. Jackson spent his political career making certain there would not be a central bank in this country. He even paid off the national debt.

The Jacksonians went on to become the modern Democrat Party. Those in favor of the national bank became the Whigs.

Why was Jackson so adamantly opposed to a central bank? Besides being unconstitutional in his eyes, Jackson was deeply suspicious of foreign ownership of the bank. That it would influence and subvert U.S. policy.

In 1822, foreigners held $3.1 million or 9.1 percent of the bank’s $35 million capital, according to a report of its board of directors. In 1830, according to a House report on the bank’s history prepared by Rep. George McDuffie that figure had risen to $7 million, or 20 percent of the stock. By 1832, it increased to $8.4 million, or 24 percent of the stock, “mostly of Great Britain,” Jackson noted in his veto of the bank’s recharter.

Even though foreigners were prohibited from serving on the bank’s board of directors, Jackson nonetheless keyed in on it as a threat to American sovereignty and independence.

“Should the stock of the bank principally pass into the hands of the subjects of a foreign country, and we should unfortunately become involved in a war with that country, what would be our condition?” Jackson asked, referring to the financial ruin that followed the War of 1812.

With the nation nearly bankrupted, that conflict had revealed very well what might happen when a nation finds itself at war with its creditors.

As far as foreign influence is concerned, consider, both Thomas Jefferson and James Madison were opponents of the national debt earlier in their careers.

Yet, their administrations accumulated vast sums of debt to foreign countries. These experiences had changed their views and thus public policy on the national debt and central banking.

President James Madison had never supported the First Bank of the United States’ charter in 1791 as a member of the House of Representatives, along with Thomas Jefferson, who both had opposed the bank on constitutional grounds. In 1811, Madison had his vice president, George Clinton, cast the deciding vote against that bank’s renewal.

Within a year, the U.S. was again at war with Great Britain, a conflict that put the nation deeply into debt. Madison, who had famously opposed the creation of the national debt, when in power saw it rise from $45 million in 1812 to $127 million by 1816 to pay for his war.

Per the McDuffie House report, within three years “the circulating medium became so disordered, the public finances so deranged, and the public credit so impaired, that the enlightened patriot, [Alexander] Dallas, who then presided over the Treasury Department, with the sanction of Mr. Madison, and, as it is believed, every member of the cabinet, recommended to Congress the establishment of a National Bank.”

So, when Madison could not lock up loans for his war — even after its conclusion — he yielded and created another central bank in 1816.

Jackson was right, foreign “investment” in our debt and our central bank is actually influence, and can turn into subversion. Madison had been transformed, and so had the implied Constitution of the federal government. The Second Bank was ordered.

16 years later, Jackson would undo it. And it would not be for another 81 years that the Federal Reserve would be created. That was Jackson’s lasting legacy.

So, whatever. Put Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill. Who cares?

If anything, the $20 bill dishonors Jackson’s true heritage as a staunch opponent of central banking and fiat currency.

So, let’s give Old Hickory his due, and get him off the $20 bill.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.