In 2012, 4.4 million seniors were enrolled in the Medicaid program, primarily for long-term nursing home or home and community care, according to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission.

Almost twice that number were on some form of long-term care — 8.3 million according to the Center for Disease Control — about comprising almost 20 percent of the 41.9 million aged 65 and over that year.

Meaning there is a 1 in 5 rate of seniors on long-term care at any given moment, and about a 1 in 10 chance of using Medicaid to receive it.

That year, it cost the Medicaid program $85.5 billion for long-term nursing home and home care targeted at elderly and the physically disabled, 20 percent of all Medicaid spending.

Taking care of those seniors was 3.8 million senior care workers — including home health care, nursing home facilities, community care facilities for the elderly and other residential care facility workers, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics establishment dataset.

That’s a little more than 2 seniors on long-term care for every 1 senior care worker.

Let’s assume the current ratio of senior health care professionals to patients are enough to provide adequate, quality care, and that the same rate of seniors will require these services into the future. Also, let’s assume the same number of workers will be necessary in the future to continue providing quality care.

Also, let’s assume costs will rise along with the growth of that population.

After all, the Urban Institute’s Melissa Favreault noted at the Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Long-Term Care Financing Colloquium in July 2015, “We project that formal long-term services and supports use and costs will roughly track the growth in the aged population.”

By 2027, there will be about 67.5 million seniors, according to U.S. Census Bureau projections. If they keep using long-term care at the same rate as 2012, then the number of patients will increase to 13.4 million, with about 7 million using Medicaid. By 2037, there will be 80 million seniors, with 16 million on long-term care, and about 8 million using Medicaid.

So, in 10 years, the nation will need about 6.1 million senior long-term care workers. To keep up with demand, then, our nation’s universities will need to churn out an additional 2.3 million from what we have today. And in 20 years, 7.3 million senior care workers will be needed, 3.5 million more than we have today.

The problem is well known. As noted by Irene Fleshner, Senior Vice President for Strategic Nursing Initiatives for Genesis HealthCare, in August 2015, “No matter what else we do; the country will need more caregivers. There’s no way around it — the current supply of long-term care workers will not meet the need of future populations. And we don’t need a study to tell us that. Heck, the current supply of workers doesn’t even meet the needs of the current population! We as a country must invest in developing more nurses, certified nursing assistants, social workers, therapists and home health caregivers.”

As the U.S. population rapidly ages then, the shortage of highly trained medical personnel looms large as one of our most pressing health care needs.

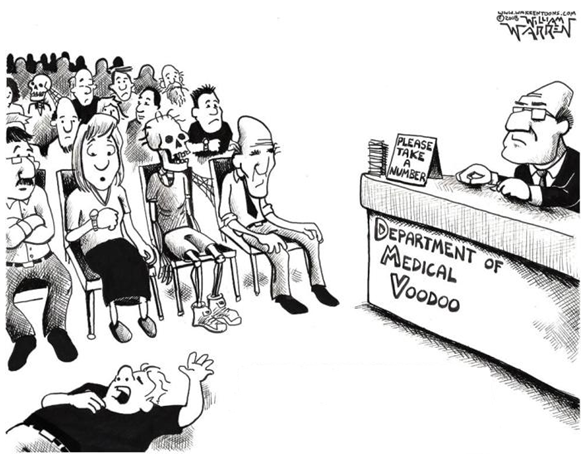

The American Medical Association (AMA) monopoly on medical schools and licensing cannot be helping. In 2009, Forbes columnist and Reason Foundation senior analyst Shikha Dalmia estimated that by shutting down “deficient” medical schools and capping the number of funded residency programs, the AMA has stunted the supply of doctors by 30 percent over the last 30 years.

That would apply not just to doctors, but to nurses and other medical professionals. Artificially constraining the supply of medical education and training creates barriers to entering the medical profession. Congress should be creating more avenues to become involved in these professions by removing red tape. Training more doctors only makes sense.

Other solutions might include refocusing the Department of Education’s financial aid program, if we’re going to be stuck with it anyway, to prioritize aid for education programs that fill in specific labor shortage needs, including in health care, on a national basis instead of just providing unlimited aid for every single major. That could be applied to other professions, too, for which there will be shortages as Baby Boomer exit the labor force.

Another major problem for long-term care is of course how to pay for these services, whether through Medicaid or otherwise. A little more than half of senior long-term care patients appear to be using Medicaid.

To the extent that Medicaid was expanded in the 2010 health care law to lower-middle income Americans who work, then, may be placing unnecessary pressure on the program that seniors are increasingly relying and will rely on in the future for long-term care. Senior long-term care spending comprises 20 percent of the entire Medicaid budget, but only about 7 percent of beneficiaries. Undoubtedly that number will rise as more seniors participate in the program.

Meaning, while Democrats were focused on their utopian vision of universal health coverage in 2010 that resulted in Obamacare, they were not focused on what would be the most pressing needs in the health care arena — hiring enough long-term care workers to take care of the aging population.

Unfortunately, the Republican plan to replace Obamacare does not address these problems, either, by ending the AMA monopoly on medical schools or ending Medicaid expansion sooner so states can marshal together resources for long-term senior care. If we’re going to be focusing patient needs in Congress’ health care proposal, without question how we take care of seniors who require long-term care will be the one of the most pressing.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.