By Printus LeBlanc

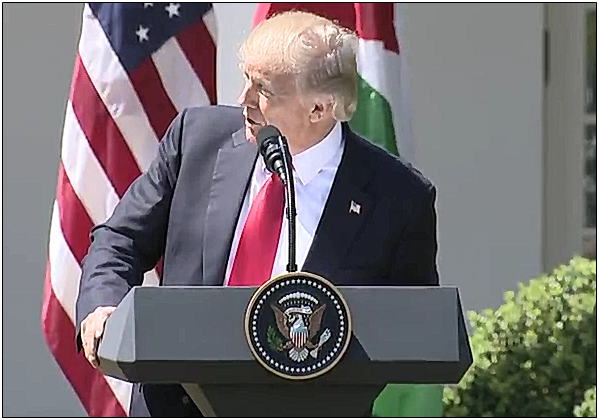

On April 5, President Donald Trump held a press conference with King Abdullah of Jordan. At it, he took the opportunity recent chemical weapons attack in Idlib that killed dozens of people, expressing his outrage, but stopped short of calling for regime change of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

The President said “I do change. I am flexible. I am proud of that flexibility. I will tell you, that attack on children yesterday had a big impact on me — big impact. That was a horrible, horrible thing. And I’ve been watching it and seeing it, and it doesn’t get any worse than that. And I have that flexibility, and it’s very, very possible — and I will tell you, it’s already happened that my attitude toward Syria and Assad has changed very much.”

The President’s statement could signal a major shift in policy. Within the past few days, White House press secretary Sean Spicer made statements affirming that the White House’s policy stance against regime change in Syria.

“With respect to Assad, there is a political reality that we have to accept,” said Spicer on March 31. “The United States has profound priorities in Syria and Iraq, and we’ve made it clear that counterterrorism, particularly the defeat of ISIS, is foremost among those priorities.”

On April 4, Sean Spicer said, “we had opportunities in the past, several years, to look at regime change. I think those are fundamentally — the landscape is fundamentally different than it is today… There is not a fundamental option of regime change as there has been in the past.”

Will the chemical attack now be a pivot point for U.S. policy towards Syria?

In 2011, the Arab Spring began. It was an uprising that grew out of displeasure with the dictatorial regimes that control the Middle East and North Africa region. The uprisings succeeded in getting some regimes to reform and others to quit. Syria on the other hand, devolved into a civil war. The civil war has been exacerbated by outside influences taking sides. The Russians, Saudis, Iranians, and the U.S. all have competing interests.

The recent chemical attack has reinvigorated the call for Assad to face war crime charges. The suspected gas attack happened after a government air strike hit Khan Sheikhoun in Idlib province. It is believed sarin gas was used. This would not be the first time the regime has used chemical weapons. The first attacks took place in 2013. The most devastating attack being rockets with sarin gas used on civilians in Ghouta, a suburb of Damascus, killed about 1,500.

That resulted in a U.S.-Russian agreement, enforced by the UN Organisation for the

Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), to disarm Syria’s chemical stockpiles. In 2015, the OPCW had declared 98 percent of Syria’s declared stockpiles had been destroyed.

But any negotiations about Syria, with Assad as president or without him, will have to include Russia. Russia has a strategic interest in the country. There is a Russian naval facility in Tartus, Syria. The base is the Russian navy’s only Mediterranean repair and replenishment spot and has been since 1971. Without the base, Russian warships would have to travel back to their Black Sea bases for support. Russia is not going to give up that base.

Rick Manning, President of Americans for Limited Government said, “Is spending our time, treasure and blood in Syria worth it? Is this in America’s interests? Does this put America first? That is the question every decision must be based on, the only premise on which we can act and no other. Taking military action as a first resort rarely turns out well. We’ve taken regime change in Iraq and again in Libya, turning both into active civil wars, and the jury’s still out in Afghanistan. May seem like a good idea, but we haven’t had much luck with it in the past decade. Regime change? To whom? Who would we be turning Syria over to? There’s little basis for civil society, religious freedom and stable parliamentary-style systems there. What comes next? For those who constantly clamor for war, the question is whether what’s left behind is better than what we had, and if regime change creates an outcome that is not in America’s interests.”

Additionally, Manning spoke about the legal implications, “There’s no authorization to use force against Syria and the Assad regime. This is an Article I question. Congress needs to debate that.”

The Assad regime does not fall under purview of either the 2001 authorization for use of military force against al Qaeda nor the 2002 one against Iraq. The first was designed to attack terrorist organizations around the globe. Presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and now Donald Trump have each used the 2001 authorization to target terrorists.

No member of Congress has introduced legislation authorizing the use of force against Syria.

As far as Syria itself, there do not appear to be any no good options.

By staying out of Syria, thousands of civilians could continue to be killed, and thousands more become refugees.

Many politicians and policy makers have brought up the idea of a safe zone. A safe zone will include a no-fly zone over the safe zone — not a risk-free proposition. U.S. Marine Gen. James Dunford, chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee on Sept. 22, 2016 that “for us to control all of the airspace in Syria would require us to go to war against Syria and Russia.”

But even if Assad could be removed from power while somehow avoiding war with Russia, then what?

The list of bad scenarios if Assad is removed is far greater than the list of good scenarios. After Mubarak stepped down in Egypt, the grandfather of al Qaeda, the Muslim brotherhood took over. After Muammar Qaddafi was killed in Libya, the country descended into civil war.

Nobody wants to repeat the Iraq invasion, and put tens of thousands of American troops into a cauldron of tribal and religious conflict in a Russian satellite state.

Nobody wants to spend hundreds of billions, if not trillions, of dollars for military actions, while the nation is drowning in nearly $20 trillion of debt.

Nobody wants to send American troops into a conflict with chemical weapons being used.

But that’s what key members of Congress are aimig for. On CNN on April 4, Sen. John McCain urged Trump to “dedicate ourselves to the removal of Bashar Assad [and]… have the Russians pay a price for their engagement…”

If members of Congress want something done about the Syrian regime and Russia, they should work with President Trump and pass legislation outlining their goals, while giving the president the authority to carry out the action. If a member of Congress is willing to call for action, they should be willing to vote on it. But they should also be mindful of the risks.

Printus LeBlanc is a contributing reporter at Americans for Limited Government.