As long as demand for the treasuries remain constant, we don’t have skyrocketing interest rates or a sovereign debt crisis — for now.

In 2020, as the global economy was shutting down, markets were reeling and governments were organizing a response to the Covid pandemic, the U.S. dollar skyrocketed in value as interest rates collapsed, even as government spending was increasingly exponentially.

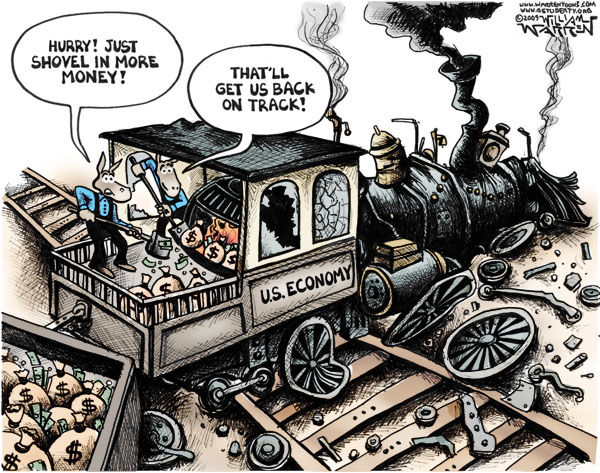

Since the start of 2020, the national debt has skyrocketed by a gargantuan $4.96 trillion amid the $2.2 trillion CARES Act and the $900 billion phase four legislation in Dec. 2020 that was signed into law by former President Donald Trump, and now the $1.9 trillion Covid response bill signed by President Joe Biden.

Some traditional views on the national debt take a supply and demand view on the topic, suggesting that as debt increases substantially, with the increased supply, interest rates will have to rise in order for the market to compensate for the increased risk and presumed inflation.

And yet, 10-year treasuries, at 1.65 percent, remain below where they were before the crisis began in mid-Jan. 2020 when the first Covid case arrived in the U.S., at 1.8 percent.

And, the trade-weighted U.S. dollar index, broad for goods and services remains about what it was in mid-Jan. 2020. Back then it was 115. Today it’s 114. But in between, it skyrocketed to a record high of 126 as demand for the dollar soared in the midst of the crisis. As a result, interest rates collapsed to less than 1 percent, but have been recovering to almost where they were previously, although not quite.

As for inflation, after experiencing deflation in 2020, we are seeing an uptick in prices in 2021, but mostly it’s a wash, with the unadjusted 12-month average being 1.7 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, pretty much in line with the Federal Reserve’s tradition 2 percent inflation target. In the coming months, that number will likely get over 2 percent, but for how long is a question.

But looking back, even though government spending was increasing dramatically, interest rates were falling, and remain below where they started before the crisis began. The contradiction comes because of the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency. During times of crisis, particularly financial crises and recessions, investors including institutional investors like banks and central banks, will buy U.S. treasuries as a hedge against the downturn. And Congress, with its voracious spending binge, has provided more than an ample supply.

Adding to the mix, the Federal Reserve has been continually intervening to purchase surplus U.S. treasuries being generated, which additionally helps to keep interest rates low. Of the $4.96 trillion of new debt that has been created, the Fed has bought $2.58 trillion, or 52 percent of the load. Financial institutions, mostly domestic U.S. institutions, have bought the rest. Foreigners barely bought any on a net basis, just a scant additional $92.3 billion.

And of the $22 trillion of the $28 trillion debt supposedly “held by the public”: $4.9 trillion is held by the Federal Reserve, $7.1 trillion is held overseas, mostly by foreign governments and central banks and just $10 trillion is held by U.S. financial institutions, businesses and organizations. The remaining $6.1 trillion is held by the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds.

So, $18 trillion out of the $28 trillion debt, or 64 percent, is held by governments: $11 trillion by the U.S. government, and around $7 trillion by foreign governments. But nobody really cares, and so institutional media and other sources continue pretending officially reported debt “held by the public” is a real statistic, even if it is incredibly misleading.

And yet, this is the major reason we don’t see skyrocketing interest rates or spiraling inflation, even with the debt spinning out of control. As if the spending binge already being undertaken were not enough, President Biden is now proposing an additional $2 trillion infrastructure spending bill, which he once again plans to pass through Congress on budget reconciliation with almost no Republican support.

But even if it were to pass, one might not expect interest rates to appreciate much more. In fact, since January, the dollar has been slightly strengthening. As much as we’re spending this year, it’s still not as much as we were spending and borrowing last year.

Yet, as more new debt enters the market from the $1.9 trillion spending bill that just passed, watch for demand for dollar-denominated assets including treasuries to increase again, which might temporarily place downward pressure on interest rates once again.

As long as demand for the treasuries remain constant, we don’t have skyrocketing interest rates or a sovereign debt crisis — for now.

Of course, the economy is still very much in dire straits despite all of the spending. There still remain 7.8 million of the 25 million jobs that were lost in the pandemic last year yet to be recovered. One should expect the economy will remain on life support for the foreseeable future, as Fed Chairman Jerome Powell remains committed to easing.

In the 2010s, however, despite keeping interest rates near-zero percent for years, it took several years for the economy to recover, from peak employment in Nov. 2007 to the bottom in Dec. 2009, saw 8.3 million jobs lost and the U.S. economy did not get them back until in Sept. 2014. Looking back at the ten recessions that have occurred since 1948, it took on average 11 months for all the job losses to be realized to get to the labor market bottom, and another 16 months to recover. The entire ordeal lasts on average 27 months.

What remains to be seen is what sort of recovery we are in. If it does take several more years to recover from the Covid recession, it certainly won’t have been for a lack of spending and borrowing more money than ever. Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.