One of former President Donald Trump’s biggest complaints during his term of office was that the dollar was too strong for him to pursue his trade agenda to boost U.S. exports and bring manufacturing back to America.

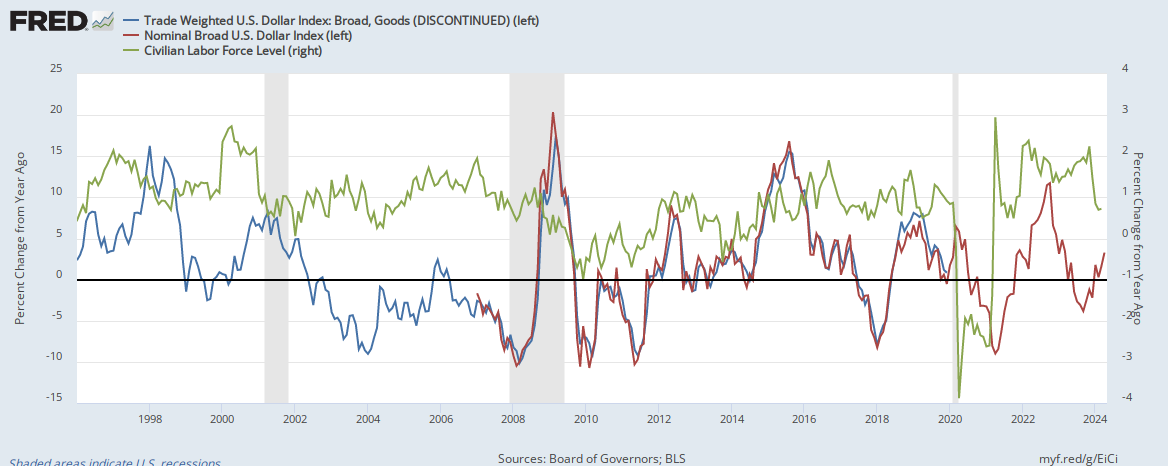

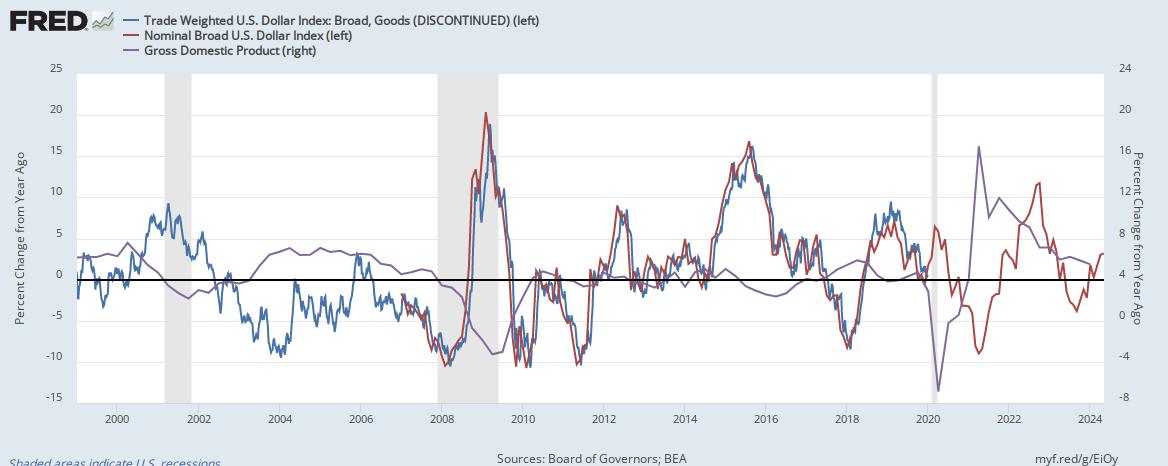

He had a point. That is because there appears to be an inverse relationship between the value of the dollar versus trade partner currencies, the so-called trade-weighted dollar index, and critical indicators including inflation, interest rates, the growth of the civilian labor force, jobs gains, exports, economic growth and so forth.

Generally, when the value of the dollar is strengthening on foreign exchange markets, central banks and financial institutions all over the world are buying up dollar-denominated assets including treasuries, U.S. corporate debt, mortgage-backed securities and so forth. And, the more demand there is for dollar assets including treasuries, particularly, when the growth rate of dollar’s value is accelerating, the weaker consumer prices, interest rates, civilian labor participation, employment, exports and economic growth become.

Conversely, when the growth rate of the dollar’s value is decreasing and weakening, you see more inflation, rising interest rates, more labor participation, greater jobs gains, exports and economic growth.

If the dollar gets too strong, you can get outright deflation. That is exactly what happened briefly last spring. As Covid struck the global economy, a flight to safety in dollar assets including treasuries ensued, bringing the dollar up to record highs versus trade partners. Deflation in some cases ensued as consumer prices dropped and the price of oil even went zero dollars briefly. 25 million jobs were lost as labor markets bottomed in April. Exports plummeted along with the Gross Domestic Product. It was an all-around catastrophe.

This occurred as overall interest rates collapsed and the Federal Reserve renewed quantitative easing, where of the more than $4.95 trillion of new debt since Jan. 2020, $2.7 trillion of it was purchased by the Fed and counting as it keeps buying $80 billion of treasuries a month, plus $40 billion of mortgage-backed securities. This has helped to push interest rates down and in the first quarter of 2020, it helped fuel the dollar to record highs.

So, here’s a question: Given the historic relationship between a strong dollar and high unemployment, was Covid responsible for 100 percent of the jobs losses, or was the economic downturn exacerbated by the strong dollar?

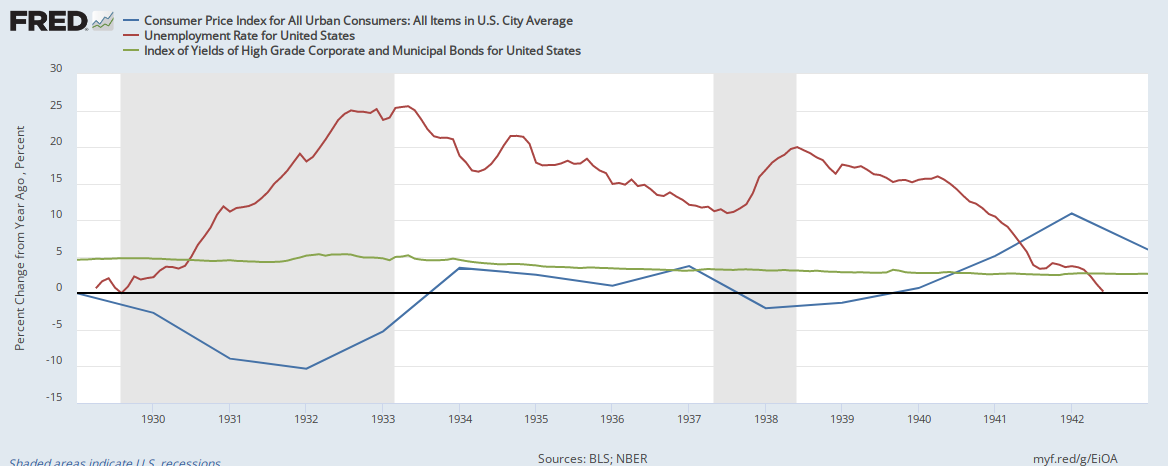

This is not such an easy question to unwind. Throughout history, currencies that were too strong have produced bouts of deflation and extremely high unemployment, for example, in the 1930s.

Deflation in the U.S. began after the great inflation of World War I and the ensuing credit expansion, had a brief respite in the 1920s before beginning again in 1927. It then slowed in 1929, and then went crazy starting in 1930 as banks began failing en masse. Inflation was marked at -2.7 percent in 1930, -8.9 percent in 1931, -10.3 percent in 1932 and -5.2 percent in 1933.

As that occurred, unemployment skyrocketed, reaching 11.2 percent by the end of 1930, up to 19.2 percent by the end of 1931, up to 25 percent in 1932 and peaked in March 1933 at 25.4 percent.

It was not until Franklin Roosevelt ended the interwar gold standard in 1933 that some relief was felt as unemployment began collapsing. Then, Roosevelt repegged the dollar to gold in April 1934, albeit at a higher price, and within a few years, deflation and dollar strength led the way to the double dip recession of 1937-1938 as deflation ensued again.

In fact, countries that abandoned the gold standard and engaged in currency devaluation and depreciation to combat the deflation saw the quickest recoveries. The countries that were the last to devalue were the worst off, a 1985 paper, “Exchange Rates and Economic Recovery in the 1930s,” by economists Barry Eichengreen and Jeffrey Sachs finds.

The United Kingdom had a similar experience of deflation following World War I, with unemployment rising dramatically in 1921 to 11 percent before falling. Then, it would rise again in 1930 to 11 percent. The UK quickly came off the gold standard in 1931, after which unemployment peaked in 1932 at 15 percent, before slowly coming back down to 7.7 percent by 1937.

Eichengreen and Sachs observe that the unilateral currency devaluations led the way in ending the depression, “In all cases of unilateral devaluation, currency depreciation increases output and employment in the devaluing country. By raising the price of imports relative to domestic goods, depreciation switches expenditure toward domestic goods. The increased pressure of demand will tend to drive up domestic commodity prices, moderating the stimulus to aggregate demand and (by reducing real wages) stimulating aggregate supply, until the domestic commodity market clears. The same effect switches demand, of course, away from foreign goods, exerting deflationary pressure on the foreign economy.”

So, because the UK was one of the first major economies to leave the gold standard in 1931, it was ahead of the game. It boosted exports and restored inflation and then unemployment began dropping.

Interestingly, as the UK went off the gold standard in 1931, inflation in the U.S. went from -2.7 percent to -8.9 percent and unemployment went from 11.2 percent to 19.2 percent. Did Great Britain’s devaluation in 1931 and other countries leaving the gold standard put the U.S., which did not devalue and depreciate until beginning in 1933, at a competitive disadvantage?

It appears so, and therefore the uneven devaluations throughout the world may have exacerbated the Great Depression in other countries that waited to devalue, leaving Roosevelt in 1933 with little choice but to engage in competitive devaluation. Per Eichengreen and Sachs, the U.S. “restricted foreign exchange dealings and gold and currency movements, and the following month he issued an executive order requiring individuals to deliver their gold coin, bullion, and certificates to Federal Reserve Banks. From this point the dollar began to float. By setting a series of progressively higher dollar prices of gold the Administration engineered a substantial devaluation. When the dollar was finally stabilized in January 1934 at $35 an ounce it retained but 59 percent of its former gold content.”

By then, the unemployment rate had begun dropping. There would be more rounds of currency battles as remaining gold bloc countries fell off the gold standard. It was not until World War II that the cycle was fully interrupted, but suffice to say, sticking the stronger dollar gold standard most certainly exacerbated the Great Depression.

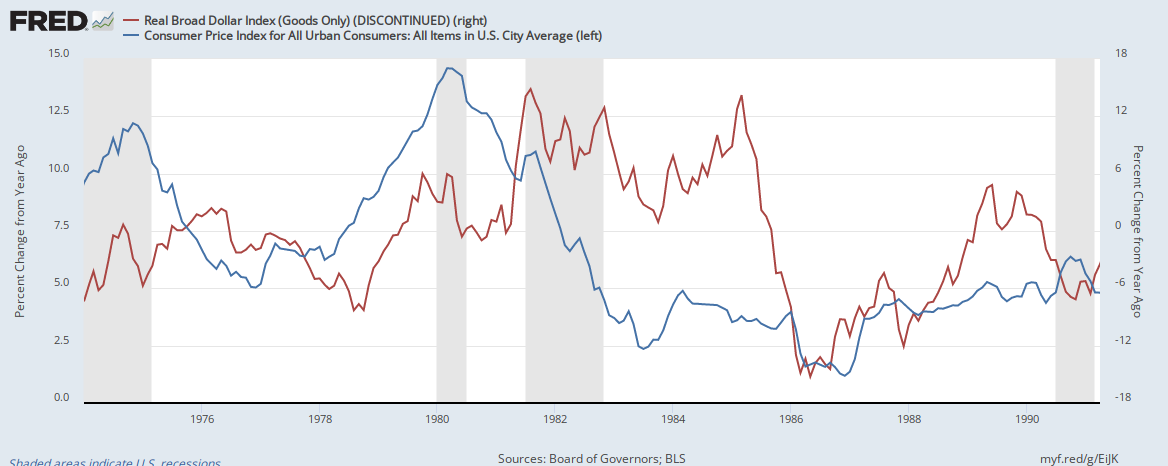

A similar relationship was established with the Great Inflation of the 1970s and the subsequent Great Moderation that followed in the 1980s and beyond. As the dollar was brought off of the gold exchange standard in 1971 by Richard Nixon, the dollar weakened at a time when 2.2 million Americans were entering the civilian labor force on average through 1980, compared with 1.1 million a year from 2010 to 2020.

The result was boom to bust cycles of jobs, wages and prices all rising dramatically, only to drop during ensuing the big recessions that followed until the 1980s when high interest rates were used to end the inflation. The difference in the 1970s is that once inflation reached sufficient levels, it would harm output and unemployment began rising too. Plus the rapidly growing number of Americans entering the civilian labor force at the time from the Baby Boom was like rocket fuel for the inflation. There would have been inflation even without leaving the gold standard again, but doing so at that moment most probably exacerbated the inflation and the ensuing unemployment.

That said, the strong relationship between deflation and unemployment has held up throughout the postwar period. When even the growth rate of prices was simply slowing down, that too has correlated with jumps in unemployment.

The Great Recession could be an episode that allowed the dollar to get too weak in the 2000s, with cheap credit fueling an asset bubble in housing, which, when it popped brough upon deflation and a massive spike in unemployment as more than 8 million jobs were lost.

In all these instances, critically, it appears the value of the dollar versus foreign currencies is a critical factor to determining how bad a recession will get.

Yes, we were going to lose jobs no matter what in 2020 to Covid thanks to the lockdowns, but that flight to safety into U.S. treasuries, driving the dollar to record highs and sucking resources from the private sector almost certainly exacerbated the job losses, which peaked at 25 million. How could it not when it has every other time? And then as soon as the dollar began weakening, more than 17 million jobs were immediately recovered.

Because the Fed didn’t listen to Trump in 2018 and 2019 when he noting that the dollar was too strong, the outcome itself might have been unavoidable without restrictions on who could purchase treasuries, but when you have the economy cratering, the last thing you want to tell banks is that they’re not allowed to purchase treasuries when they want them the most. And so the dollar just kept right on getting stronger until the Fed engaged in aggressive quantitative easing, to soak up as much whatever of the new debt U.S. financial institutions and foreign banks could not. Then, when trillions of dollars in new debt was being injected into the economy, the value of the dollar finally began collapsing off their too-strong levels and jobs came back in a hurry.

It appears clear that throughout history that the relative value of the dollar absolutely has a relationship to how many jobs the economy can produce or lose. If it fluctuates too wildly in either direction, it can be really bad for the economy. The lessons from the 1930s, the 1970s, the Great Recession and the Covid Recession is that neither too much inflation or deflation are good for the economy, and that price stability is much preferred.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.