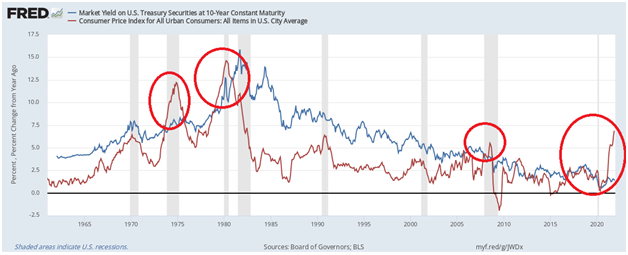

In modern U.S. history, when inflation has outpaced interest rates like it is now, they were associated with recessions in the 1970s and 1980s.

“Supply and demand imbalances related to the pandemic and the reopening of the economy have continued to contribute to elevated levels of inflation… Progress on vaccinations and an easing of supply constraints are expected to support continued gains in economic activity and employment as well as a reduction in inflation.”

That was the Federal Reserve on Dec. 15, outlining its view that the hot inflation coursing through the U.S. economy — currently 6.8 percent for consumer inflation and 9.6 percent for producer inflation — is being caused by the current global supply chain crisis that began during the Covid pandemic in 2020.

While there is also a slight reference to “demand imbalances,” that is putting the matter mildly. Since the pandemic began, Congress has engaged in an onslaught of unprecedented new spending: the $2.2 trillion CARES Act and the $900 billion phase four legislation under former President Donald Trump, and the $1.9 trillion stimulus and the $1.2 trillion infrastructure with $550 billion of new spending under President Joe Biden.

That’s $5.5 trillion of new spending in just two years, coming atop the regular budget, and has helped add $5.7 trillion to the national debt, which now totals $28.9 trillion.

In addition, the Fed expanded its balance sheet by $4.4 trillion all the way to $8.6 trillion, more than doubling its holdings of treasuries and increasing its mortgage-backed securities by more than $1 trillion.

It is the most accommodative central bank policy since Ben Bernanke in 2009 and 2010 during the financial crisis in a bid to keep interest rates low.In addition, the Fed has held short-term interest rates to near-zero percent throughout the pandemic.

Here, again, the Fed makes a vague reference to these policies, stating, “Overall financial conditions remain accommodative, in part reflecting policy measures to support the economy and the flow of credit to U.S. households and businesses.”

But it understates the significance of those policies. Here they are: In sum, as a result of Congress and the Fed’s accommodation, the M2 money supply has increased by more than $5.7 trillion since Jan. 2020, a gargantuan 37.5 percent increase.

What more is needed to explain the current bout of inflation?

Between the treasuries purchases, which will continue at $40 billion a month and the mortgage securities, which will continue at $20 billion a month, and the artificially low short-term interest rates, longer term paper like 10-year treasuries have low interest rates, too.

In modern U.S. history, when inflation has outpaced interest rates like it is now, they were associated with recessions in the 1970s and 1980s, removing what would otherwise be a cooling mechanism on the high inflation.

Now, to be fair, the policies to date both under Trump and Biden were geared towards eliminating the record high unemployment during the pandemic, when as many as 25.3 million jobs were lost by April 2020.

Since then, labor markets have come roaring back, recovering 21.8 million jobs and counting (16.6 million under Trump and 5.1 million under Biden).

Similarly, the unemployment rate itself has collapsed from 14.8 percent in April 2020 to just 4.2 percent in Nov. 2021. So, mission accomplished, right?

Democrats in Congress don’t seem to think so. Fearful of losing control of the House and the Senate in the 2022 Congressional midterms, Congress is still trying to tee up another $2 trillion of environmental and social spending.

It would only add to the inflation. But, the legislation might be in trouble as Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) still has not reached an agreement with his own party on the final details of the bill,which is now postponed until next year, threatening the Biden legislative agenda perhaps for the next several years.

On the other hand, if Manchin goes along with that bill, and the inflation remains persistent into 2022 and beyond,the Biden economy really could be a repeat of the 1970s that ultimately caused Jimmy Carter to be a one-term president. The price of failure is high.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.