After Covid, the employment population ratio of 16- to 64-year-old working age adults — the percentage of people legally eligible to work who are working — has declined 1.9 percent, from a peak of 71.4 percent in 2019 to 69.4 percent in 2021, according to an Americans for Limited Government Foundation analysis of unadjusted annual average data compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That is little better than 2016, when it registered 69.35 percent, as Covid erased all the gains made by labor markets during the Trump economy from 2017 to 2020. The peak in labor markets of 2019 had been the highest 16-64-year-old employment population ratio reading since 2007, before the financial crisis.

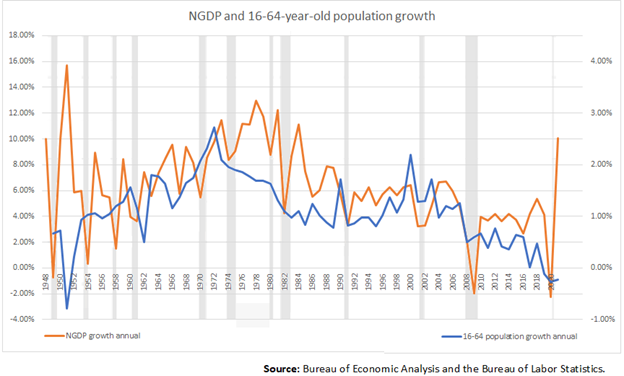

And that was with the population of 16-64-year-olds declining by 1.1 million since 2019, from 206.3 million to its 2021 average level of 205.2 million. The 16- to 64-year-old population in the U.S. recently peaked in 2018 at 206.5 million as Baby Boomers have reached retirement age en masse, more than offsetting the overall population growth of 16-64-year-olds, which has slowed almost entirely due to declining fertility in the U.S. since birth control was widely adopted in the West.

The current employment population ratio reading of 69.4 percent represents a 2.8 million jobs gap for working age adults that still remains from 2019 to 2021 as the U.S. economy continues to recover from the global economic lockdowns that cost 25 million jobs by April 2020.

The result is a labor supply crisis.

Which is too bad, because the next recession may already be on the horizon, this time triggered by an overheating economy after Congress spent and borrowed more than $6 trillion to fight Covid after Jan. 2020. Since then, the M2 money supply has skyrocketed by more than $6.4 trillion to $21.8 trillion, the highest ever, and inflation is raging at 7.9 percent.

In the five recessions that preceded the Covid pandemic recession, each time inflation got above 5 percent, on average within 14 months there was another recession in the U.S.

Meaning, there might not be enough time to get labor markets as represented by the employment population ratios back to where they were before the next recession strikes — which could set overall progress back several years, along with the careers of younger Americans.

Here’s the long-term concern: Given the historical connection between the working age population and economic growth, a declining 16-64-year-old working age population will almost certainly mean slower real economic growth going forward, with or without inflation.

In Japan, similar trends long term have led to outright deflation, negative interest rates, central bank purchase of equities and other creative maneuvers to boost asset prices even with shrinking labor markets.

In Europe, too, these demographic declines have also been painful, with the same pattern: a slowing working age population and economy.

Once the current bout of inflation has run its course and the economy overheats, the U.S. could plunge into another recession and even deflation. If labor markets do not lead a quick recover, that might lead Congress to respond with yet more spending, borrowing, and printing — creating another inflationary cycle. But all the helicopter money in the world could never accomplish what a growing labor market could.

Grow, or die. That’s the essential lesson that Japan and Europe teach us. With a healthy growth of labor markets, over time, positive economic growth without high inflation is attainable. Without it, and the growth engine of the economy — and capitalism itself — can grind to a halt.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.