“Our expectation has been we would begin to see inflation come down, largely because of supply side healing. We haven’t. We have seen some supply side healing but inflation has not really come down.”

That was Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell on Sept. 21, speaking to reporters following the central bank’s meeting where the Federal Funds Rate was once again increased 0.75 percent to its current range of 3 percent to 3.25 percent in a bid to combat sticky 8.3 percent consumer inflation the past year.

To be sure, inflation has been above 5 percent for 15 straight months now dating back to June 2021, and the Fed was late to react, not hiking rates the first time until inflation was already above 8 percent in March 2022.

Even now, the rate the Fed is charging banks to borrow is nowhere near to inflation rate, which is unusual for most of the Fed’s history. Throughout the postwar period — with the notable exception of the mid-1970s — the central bank would keep interest rates well above that of the inflation rate, something that was true until the dotcom bubble popped in the late 1990s.

Then, starting in the 2000s, it stopped doing that. It let the inflation rate run above bank borrowing rates and asset bubbles formed everywhere, particularly in housing, which eventually crashed, leading to an even more pronounced spread between inflation and borrowing costs under Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke who moved towards the zero-bound interest rates structure that persisted throughout the Obama years, and even as rates increased during the Trump years, it was still less than the rate of inflation.

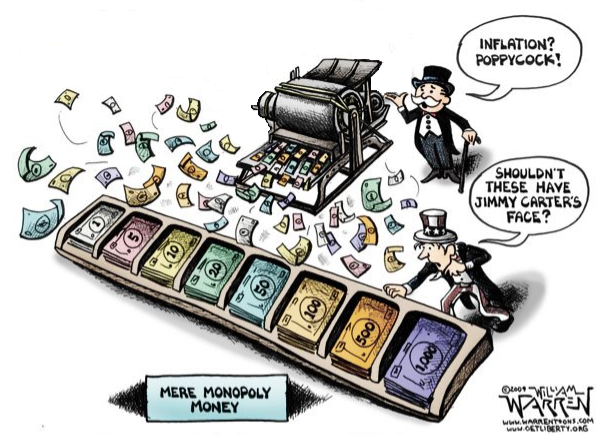

That is relatively cheap credit—a way to boost consumer spending and to prevent households from getting underwater—but because it comes at times of vast expansions of federal government spending, on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, Medicare expansion, the financial crisis, the stimulus, Obamacare, defense expansion, Covid, checks, forgivable small business loans, etc. the unfortunate side effect is more money is being created than destroyed, and at a rate faster than the economy can grow.

From 2001 to 2020, before Covid, the national debt increased from $5.7 trillion to $23.2 trillion, a 307 percent increase. Meanwhile, the M2 money supply increased from $5 trillion to $15.4 trillion, a 208 percent increase, while the nominal Gross Domestic Product increased from $10.5 trillion to $21.6 trillion, just a 106 percent increase. Whatever we couldn’t borrow from the domestic and global economy’s financial system, we printed.

Our spending, borrowing and printing has far outpaced economic growth. In the past inflation was averted by running massive trade deficits but also tends to come down in really big recessions, when the reverse problem, deflation, comes into play. We’re still running massive trade deficits, but now it’s no longer enough to offset the sheer amount of borrowing and printing. Since Covid, the M2 money supply has increased another $6 trillion, to its current level $21.6 trillion.

Since inflation is defined as too much money chasing too few goods — and both factors are notably at play — to the extent that the real economy cannot keep up with demand via production, the implication is that whatever cannot be done to boost production therefore must be taken out of the money supply in order to combat the inflation, hence the interest rate hikes. But are they enough?

So far, since the Fed’s rate hikes, there is not too much money destruction. M2 peaked in April at $22 trillion and now about $400 billion have been destroyed, a 1.8 percent cut, coming off a 44 percent increase. Is that enough?

That’s a lot of excess money supply to sop up. While producers continue catching up to global demand following the Covid lockdowns, central banks have a supply problem as well to contend with, but must be careful not to spark outright deflation. 30-year mortgage rates are 6.3 percent now and 10-year treasuries are about 3.73 percent. Those are pretty high compared to recent history, but are they high enough to destroy even some of the money we created during Covid?

The proof will be in the pudding. There are still uncertainties related to continued supply disruptions to Europe’s natural gas supply amid the worsening war in Ukraine atop artificial constraints on energy production as President Joe Biden attempts to transition America to a green economy and oil production is still below pre-Covid levels, and just how bad the current recession will be as it relates to labor markets disruption. Unemployment is still historically low at 3.7 percent and tends to be a lagging indicator in recessions.

For now, it appears that the Fed is betting that with inflation still high, until labor markets offer their own recession signal, it still has room to hike interest rates some more until either the inflation rate comes down or unemployment goes up — or both. Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.