The Federal Reserve hiked its core interest rate for banks up once again another 0.75 percent to 3.75 percent to 4 percent on Nov. 2 as high consumer inflation persists in the U.S. economy, and prepared markets for more rate hikes to come until the inflation gets under control.

According to the Fed’s statement, “The Committee anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time.”

That is lower than it was in 2007 at a time when inflation itself was much lower, but the Fed might still be feeling a bit shell-shocked from the last time they needed to hike interest rates.

Back then, the peak effective Federal Funds Rate was about 5.25 percent in the summer of 2006 after inflation hit 4.7 percent in Sept. 2005.

That was at a time when housing prices particularly were soaring, and had the near term impact of cooling consumer inflation and the growth of the M2 money supply, but the Fed began easing as home values and sales began plummeting in the summer of 2007.

But as the Fed took its foot off the brake to address the housing recession, inflation and the M2 money supply kept accelerating with inflation hitting 5.5 percent July 2008 as oil prices went to the moon.

By then, the credit crunch was already well underway as the U.S. economy was being consumed by a massive recession. Banks had collateralized their mortgage-backed securities holdings, never taking into account how deeply prices would fall.

At the time, there was no backstop for housing. But since the financial crisis, the Fed has recycled mortgage credit by taking on trillions of dollars over time of mortgage-backed securities into its own portfolio, essentially eating the bad debt and making explicit the implicit guarantee that always carried with Government Sponsored Enterprises’ (GSE) paper via Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which remain under conservatorship by Congress.

Surely, the Fed wants to address inflation — housing prices are up 10.3 percent year over year as of the third quarter of 2022 according to the U.S. Census and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and were up 21.8 percent as of Q3 2021 — but it also does not want to spark deflation, either.

Usually, when the Fed is lowering interest rates, the money supply accelerates with inflation, and when it hikes interest rates, the money supply growth slows down and so do price increases, an analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics and Federal Reserve data shows.

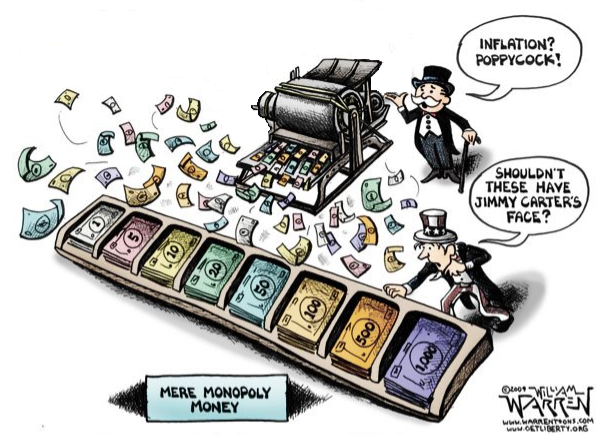

2020 might be the best example of this, as the federal government spent, borrowed and printed about $6 trillion to combat Covid, at the same time the Fed took interest rates down to near-zero percent, a massive torrent of money creation at the same time global production had ground to a halt. Then with all the extra money floating around, demand immediately picked up again, but production had not.

Where do you think all the inflation came from? But how to unwind it is a better question. The extra money has to be destroyed.

But if the money supply contracts too quickly, so will prices, again eating up home equity as in the 2000s. On the other hand, home sales are already contracting and prices slowing down in the near term. Existing home sales have also collapsed 27.4 percent since Jan. 2022 to 4.7 million annualized, according to National Association of Realtors (NAR) data. That mirrors 2007 and 2008 collapses annually of existing home sales of 22 percent and 18 percent, respectively, as home sales fell from their 2005 high of more than 7 million to just 4.1 million by 2008, but without the price decreases.

So, we’re not nearly in the same situation. By backstopping mortgage securities since 2008, the Fed should be more able to address core inflation concerns without worrying it could upset the apple cart, whereas in the 2000s perhaps the infrastructure was not there to deal with the massive feedback this might cause if the credit system were not functioning as it should and defaults were driven by homeowners’ decisions to walk away from their mortgages.

The question does not appear to be whether interest rates need to be hiked at the Federal Funds Rate level — what other mechanism is there to destroy all the extra money we printed? — but by how much, and how quickly. With inflation over 5 percent since June 2021, the Fed has already waited to hike rates past that of the consumer inflation rate.

In the meantime, U.S. consumers are already paying higher interest rates, with 30-year mortgages going for more than 7 percent. It’s the banks’ interest rate that is being kept artificially lower. This will cause U.S. consumers to spend more of their own money to service debt, which eventually the Fed will eat when the banks have to pay their own credit costs via higher interest rates.

What normally happens is a recession intervenes, unemployment goes up, demand drops and prices then cool off, which is what the Fed appears to be waiting for.

But the danger of not conceding the recession now by, say, hiking rates past the inflation rate, as in every other economic cycle since World War II, inflation could again worsen, potentially prolonging the cycle and leading to an even larger recession later, especially as global supply and labor shortages remain ongoing problems, which will keep upward pressure on prices. Either way, with interest rates rising for the foreseeable future, that means we will all be paying off the Covid debt for some time to come.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.