Despite taking action to put Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank into receivership under provisions of federal law in the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial legislation by the U.S. Treasury, Federal Reserve and FDIC on March 12—as much as $230 billion of uninsured deposits in these two banks are now being guaranteed—regional bank stocks have continued tanking amid a continued run, not on deposits per se, but on bank stocks.

For example, First Republic Bank’s stock value is down 73 percent the past month as of this writing as investors withdraw from the capital side of the equation. Overall, the SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF is down about 26 percent the past month in a similar flight of capital away from bank stocks, and especially regional ones.

Now, Wall Street is in a rush to recapitalize these banks with a reported $30 billion infusion into First Republic. Notably, this is a bid to put deposits into the bank, and not to buy the stock itself. Why?

Simple. Under the terms of putting Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank into receivership, per the U.S. Treasury, Federal Reserve and FDIC joint statement on March 12: “Shareholders and certain unsecured debtholders will not be protected.” This was a provision of Dodd-Frank, 12 U.S. Code Section 5390(a)(1)(M) which states “The Corporation shall ensure that shareholders and unsecured creditors bear losses, consistent with the priority of claims provisions under this section.”

So, why would any rational small-time investor wish to hold onto a regional bank stock under these current circumstances and perverse incentives? It’s either sell now and get to keep some of your money, or get nothing later if the company is put into receivership.

In fact, the run on deposits at Silicon Valley Bank was preceded by the bank issuing a statement that it needed to raise more capital, not the other way around. Late on March 8, the bank stated it needed to raise $2.25 billion in new capital: “We have sold substantially all of our Available for Sale (AFS) securities portfolio with the intention of reinvesting the proceeds, and commenced an underwritten public offering, seeking to raise approximately $2.25 billion between common equity and mandatory convertible preferred shares.” The raising of capital was to offset losses on treasuries and mortgage-backed-securities. At that time, the stock share price was $267.83. On a call with investors, the bank urged everyone to “remain calm.”

Then, on March 9, the opposite happened. Following the bank’s attempt to raise the additional $2.25 billion, Founders Fund, Coatue and other firms advised clients to put their funds somewhere else. As Bloomberg News reported on March 9, “Panic spread across the startup world Thursday after a warning from Silicon Valley Bank, a major lender to fledgling companies, prompted Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund and other prominent venture capitalists to advise portfolio businesses to withdraw their money.”

Read that again: “after a warning from Silicon Valley Bank,” that is when “[p]anic spread across the startup world…” which “prompted Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund and other prominent venture capitalists to advise portfolio businesses to withdraw their money.”

That’s what spooked investors and sparked the bank run when as much as $42 billion was removed from the bank. As a result of the bank’s attempt to raise capital, the stock tanked to $106.04 before trading was halted. Smart investors knew that because deposits at the bank were well in excess of the $250,000 statutory FDIC limit for insurance, with the bank stating it was undercapitalized, that it could not possibly withstand a bank run.

Here’s the dirty little secret. No private bank, no matter how well capitalized, can possibly withstand a bank run, a quick look at capital ratios of major financial institutions shows. For example, JP Morgan had a capital ratio of just under 12.2 percent as of the second quarter of 2022. Bank of America was at 10.5 percent. Wells Fargo at 10.4 percent. And so forth.

The implication is that if more than 13 percent of bank customers were to go to withdraw their funds at any of these banks, they would fail. This is a well-known structural flaw of fractional reserve banking. Almost a century after 1929, and practically nothing has changed. Sure, the laws and regulations are different. The gold standard is long gone. The FDIC now insures deposits.

But the core issue—banks lend out far more than they keep on deposit and via capital—has never, ever been resolved to anyone’s satisfaction, as evidenced by financial crisis after financial crisis, whether the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s or the financial crisis of 2007-2009.

Of course, everyone will try to assure you otherwise. U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on March 16 just went out there to proclaim to Congress that “Our banking system is sound…” Sure, it is.

And yet, according to a Federal Reserve history, which Yellen once headed under former President Barack Obama, the savings and loan crisis mirrors today’s current problems and was prompted by a bid to rein in the hyperinflation of the 1970s and 1980s with higher interest rates.

Per the Fed: “Inflation rates and interest rates both rose dramatically in the late 1970s and early 1980s. This produced two problems for S&Ls. First, the interest rates that they could pay on deposits were set by the federal government and were substantially below what could be earned elsewhere, leading savers to withdraw their funds. Second, S&Ls primarily made long-term fixed-rate mortgages. When interest rates rose, these mortgages lost a considerable amount of value, which essentially wiped out the S&L industry’s net worth.”

Why, that’s exactly the same problem as today. In fact, Silicon Valley Bank’s exposure to U.S. treasuries and mortgages—whose interest rates have risen as inflation has swept over the U.S. the past two years as the economy overheated—is not unique. Every large bank buys treasuries and mortgage securities. Currently, banks are said to be sitting on more than $620 billion of unrealized losses.

The implication is that any attempt to normalize interest rates after former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke set them near-zero percent in Dec. 2008 will be met with financial contagion—even and especially if the higher rates are the only mechanism available to rein in high inflation by soaking up excess dollars that were chasing too few goods.

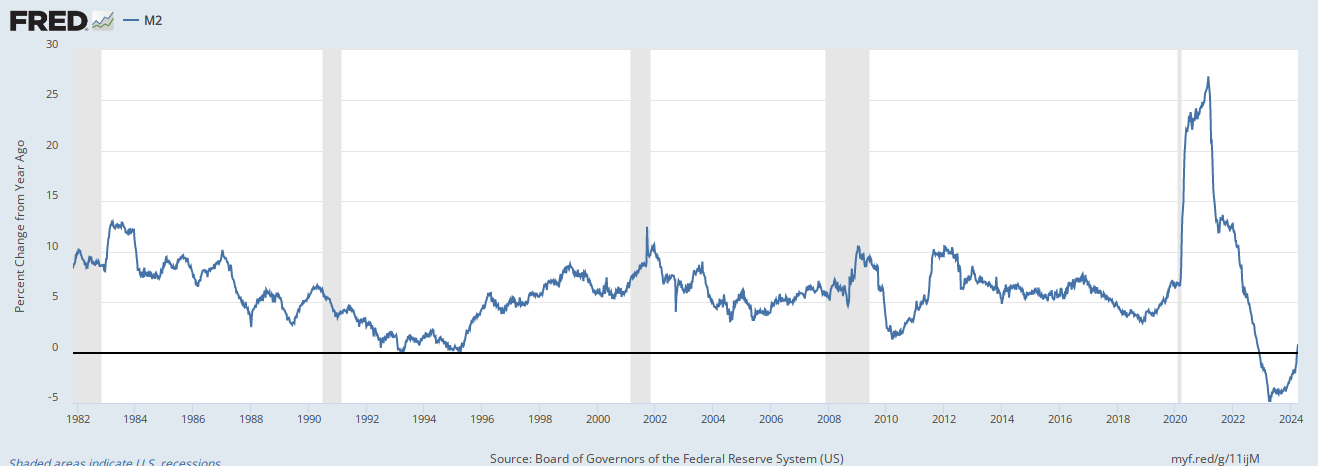

On that count, the M2 money supply, which peaked at $22 trillion after it increased dramatically from $15.3 trillion in Feb. 2020 to a peak of $22 trillion by April 2022, a massive 43.7 percent, after more than $6 trillion was printed, borrowed and spent into existence for Covid, has now decreased a bit to $21.1 trillion, and is down 1.9 percent over the past 12 months. One has to go back to the Great Depression and the banking crises of the late 1800s the last time that happened.

And yet this was always the danger of printing so much money in the first place. A lot of inflation, followed by predictable deflation when either the growth of the money supply slowed down or started contracting when interest rates would inevitably start rising, as they have.

Now, markets are actually pricing in an interest rate cut at the Federal Reserve’s next meeting after the Fed had already broadcast it was going to continue hiking rates. An about face now might be seen as a vote of no confidence in its own analysis and its rescue plan to date to protect depositors if not shareholders at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank.

The issue remains capital, where the way the spark a bank run is to publicly ask for more money—as required by law—to cover predictable losses in a rising interest rate environment. Not that Congress should cover the capital that underlays banks anymore so than it should attempt to guarantee stock market values and 401ks—which the FDIC does not insure—or Individual Retirement Accounts above $250,000. All told, retirement savings total more than $32 trillion nationwide according to data compiled by the Investment Company Institute. The Fed couldn’t cover all of that if it tried.

The other issue, of course, is leverage. Did banks really just invest and lend the newly minted $6 trillion for Covid all away because they could? Where did most of it go? The Fed sure didn’t seem to care too much at the time, but seeing as the national debt grew by about that much and home values are still way up, treasuries and mortgage-backed securities might be the first place to look.

Depositors didn’t buy the treasuries and mortgage-backed securities per se, the banks did. The depositors are just hostages against the $620 billion of unrealized losses. It’s “Don’t hike rates or the economy gets it!”

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.