Since the beginning of 2020, marketable U.S. treasuries have increased by $7.5 trillion as the total national debt ballooned to $31.4 trillion, and mortgage debt has increased by $2.4 trillion to $11.92 trillion, according to the latest data compiled by the U.S. Department of Treasury and the New York Federal Reserve.

Of the $7.5 trillion, $3 trillion was bought by the Federal Reserve, which took its holdings up to $5.3 trillion since the beginning of 2020 and about $600 billion was bought by foreign financial institutions including foreign central banks since then. The foreign exposure on treasuries had been up to $900 billion as of Dec. 2021, but they appear to have divested by about $300 billion since then.

Which means the other $3.9 trillion was bought by U.S. financial institutions, at a time when interest rates were much lower than they are today. Banks are said to be sitting on more than $620 billion of unrealized losses.

But one curious feature of the federal takeovers of the Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank has been that treasuries that had been held at that bank are being purchased by the Fed for 100 pennies on the dollar. The new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), according to its terms states “the collateral valuation will be par value. Margin will be 100% of par value.”

As explained by Bloomberg columnist Matt Levine, “if you bought Treasury bonds a year ago at 100 cents on the dollar, and they’re worth 80 cents on the dollar today, and you’re a bank, you can put them into the BTFP and borrow 100 cents against them. This means that BTFP is not a perpetual program to let banks ignore mark-to-market accounting forever: It is a way for banks to roll off their existing portfolios of Treasuries that have lost value in the current rate-hiking cycle, to transition to a steady state where (you hope!) banks are less at risk from interest-rate increases.”

So rather than purchasing treasuries on the open market as the Fed normally does, in the case of these banks, while shareholders and bondholders of the banks themselves are getting nothing, the treasuries bondholders are being made whole for about the next year or so. Until that’s not enough.

The same thing happened with the Fed’s program to purchase mortgage-backed securities after the financial crisis. We started with the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) which was supposed to make loans to banks until they could get on the right side of their balance sheets. But thanks to the Fed audit ordered in Dodd-Frank, it was revealed that in its $1.25 trillion of full-on bailouts of financial institutions, mortgage-backed securities were also bought for 100 cents on the dollar and a whopping $442.7 billion went to foreign banks to bail them out, too.

Undoubtedly, another audit of the Fed’s rescue programs will need to be done after this recession as well to see the full extent of the quantitative easing was used to obtain a 100 percent bailout to prevent banks from experiencing losses. In the meantime, the losses the American people will experience in this recession, including higher unemployment—as many as 2 million jobs could be lost—foreclosures and other fallout will be real enough.

The current growth in treasuries was predicated upon a massive government spending program from 2020 through 2022 on the Covid pandemic in a bid to boost demand at a time when there were economic lockdowns, production halts as people were paid to stay home and a huge spike in unemployment at 25 million jobs were temporarily lost.

As a result of all the spending, borrowing and printing, inflation skyrocketed, leading to the inflation spike, where consumer inflation reached 9.1 percent in June 2022. By the time Russia invaded Ukraine in Feb. 2022—further worsening global supply issues—consumer inflation was already north of 7.5 percent. Now it’s down to 6 percent as consumer begin to max out on credit.

And so is the the M2 money supply, which peaked at $22 trillion after it increased dramatically from $15.3 trillion in Feb. 2020 to a peak of $22 trillion by April 2022, a massive 43.7 percent, after more than $6 trillion was printed, borrowed and spent into existence for Covid, has now decreased a bit to $21.1 trillion, and is down 1.9 percent over the past 12 months. One has to go back to the Great Depression and the banking crises of the late 1800s the last time that happened.

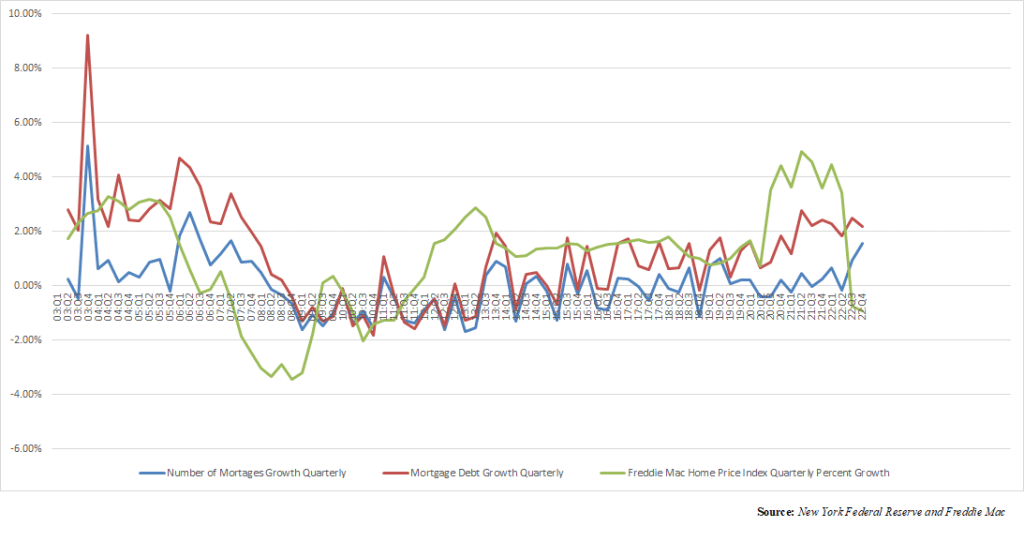

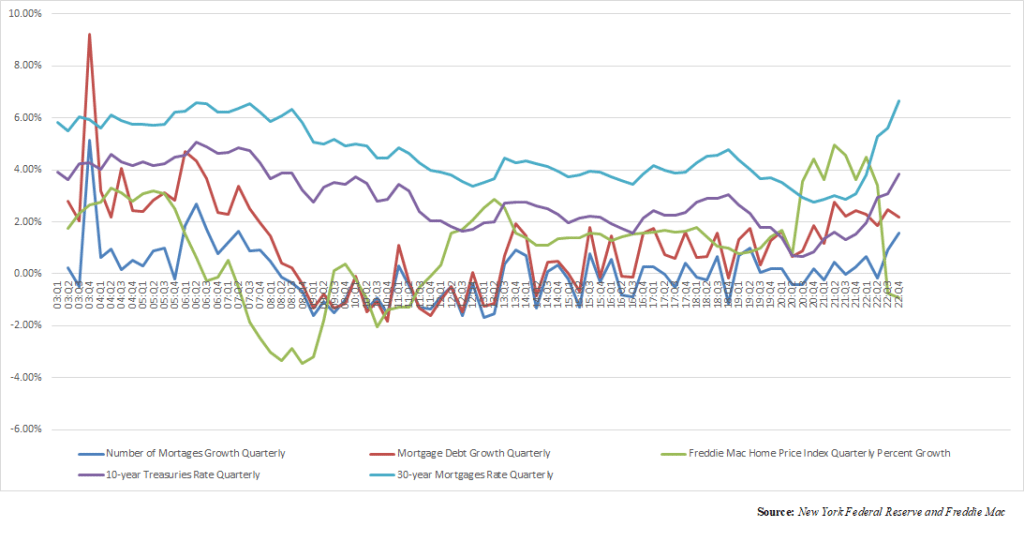

But that’s not the only thing collapsing. Don’t look now, but home values are just starting to collapse, according to latest readings of the Freddie Mac Home Price Index, after skyrocketing at rates even greater than they did during the 2000s housing bubble. Quarterly growth of home values peaked at 3.29 percent in the fourth quarter of 2002, whereas the quarterly growth in the most recent cycle peaked at 4.96 percent in the second quarter of 2021. That is absolutely massive.

I compiled these charts with the New York Federal Reserve and Freddie Mac data, plus interest rates, into a spreadsheet into a spreadsheet so you can see for yourself.

The declines have come just as interest rates have been increasing, which they inevitably were going to in order to tame the inflation that was caused by printing more than $6 trillion in the first place. 30-year mortgages peaked at more than 7 percent in Nov. 2022 and 10-year treasuries peaked at 4.25 percent in Oct. 2022.

It was because of all the funny money. Checks to households, continued unemployment claims for millions of households, continued Medicaid enrollment for an additional 20 million Americans that nobody in Washington, D.C. likes to talk about (well, Democrats do to their constituents, that was their socialized medicine scheme), more deficit spending subsidies for green energy and so forth.

The news comes as existing home sales have collapsed from an annualized rate of 6.3 million in Jan. 2022 to 4 million in Jan. 2023, according to data compiled by the National Association of Realtors, a dramatic collapse of 36 percent in just a year as prices peaked and got too expensive, plus interest rates hike upwards.

What a difference too much spending and then subsequent inflation and higher interest rates can make. In the 2000s, the bubble was predicated by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and other mortgage lenders—a massive injection of credit as mortgage debt nearly doubled from $4.9 trillion in 2003 to $9.29 trillion by the end of 2008, according to the New York Federal Reserve data. The number of mortgage holders had skyrocketed from 80 million in 2003 to 98 million in 2008.

Today, the size of residential mortgage lending has not grown by nearly that much, although it is still substantial, growing 48 percent in the past decade from $8 trillion to its current level $11.92 trillion.

The real growth has come in the way of commercial and multifamily real estate lending, which has grown from about $2.5 trillion a decade ago to $4.45 trillion, a 78 percent increase, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. And whereas residential lending has not one but two explicit government backstops—Fannie and Freddie have been in conservatorship since 2008 and the Federal Reserve has never stopped buying mortgage backed securities, of which it owns now $2.6 trillion—commercial real estate has more of an implicit backing.

That is thanks to rules that allow for 35 percent of Delegated Underwriting and Servicing (DUS) multifamily apartments to be occupied by commercial tenants or they can derive 20 percent of income from commercial sources. Implicit backing of residential mortgages and mortgage-backed securities in the 2000s preceded explicit government backing when prices went south and there was a negative equity crisis in the 2000s.

Today, we’re potentially headed into negative equity and the commercial real estate bubble is another source of potential problems.

Once you get beyond the multifamily lending, there is no government backstop for the commercial real estate lending industry per se. Should we have another full blown mortgage and then financial crisis, the pressure will become for the Federal Reserve to not only buy residential mortgage backed securities, but the commercial real estate ones as well.

Right now, we’re already seeing the stress that regional banks like Silicon Valley Bank and big ones like Credit Suisse are put under when interest rates have risen because of the inverse relationship between bond values and rates. When rates go up, the value of the bonds you bought yesterday go down. It’s impacting big and small banks alike.

What a stupid system. And a misallocation of resources. We could be investing in boosting production in America, fixing our crumbling infrastructure, improving our schools and so forth, but our financial system for more than a century is built on making supposedly private banks profitable by chasing the dollar and interest rates around boom to bust economic cycles.

If the system were well capitalized and could withstand a hit, then treasuries holders would not need 100 pennies on the dollar for the bonds they bought when interest rates were low. That should be as alarming as it was more than a decade ago when the same thing happened for mortgage-backed securities. Again, this is a well-known flaw of the fractional banking system, that banks lend out far more than they keep either on deposit or via capitalization.

And when that system fails, as it has continually done, the result is only ever more consolidation of the financial system, socializing the risk of too big to fail, but ultimately leading to a public-based financial system as the quasi-public-private one we have becomes too big to save.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.