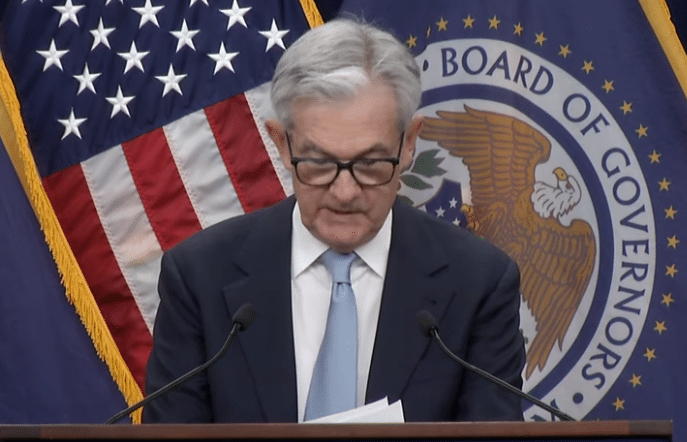

The Federal Reserve Board of Governors after its March 22 meeting once again hike the Federal Funds Rate, this time to a range of 4.75 percent to 5 percent, in a bid to calm consumer inflation that remains elevated at 6 percent, with at least one more interest rate hike expected at the next meeting from May 2 to May 3.

That is, assuming the wheels don’t fall off the U.S. economy in the meantime with the current seeming banking crisis after $230 billion of uninsured deposits were guaranteed in Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, which were placed in FDIC receivership on March 12, where some mid-sized regional banks were caught overexposed with too many treasuries and mortgage securities purchased when interest rates were much lower.

All told banks are said to be sitting on some $620 billion of unrealized losses related to rising interest rates, but so far, the Federal Reserve does not appear to be concerned too much, even if markets were. Prior to the Fed meeting, just a week earlier, CME Group data showed as high as a 65 percent probability of there being no rate hike when traders were asked on March 15.

Powell hinted at the further rate hike when he said “the median participant projects that the appropriate level of the federal funds rate will be 5.1 percent at the end of this year…” Since the current Federal Funds Rate only comes up to 5 percent, that means most of the Board of Governors are expecting the rate to be above 5 percent by the end of the year, after which time it might stay there until inflation returns to much lower levels.

On the other hand, unless there is another inflation spike, there was a 1.2 percent monthly increase in inflation in March 2022, a 0.3 percent increase in April 2022, a 1.0 percent increase in May 2022 and a 1.3 percent increase in June 2022—and all those are about to fall off the 12-month inflation indicator. Any numbers significantly lower than that, say, it was half that, then by June 2023, inflation might be as low as 4.1 percent.

Meaning, the consumer inflation rate, barring another runup, could be about to fall below that of the Federal Funds Rate sooner rather than later. It might have already been there, but the Fed did not appear to wish to raise rates too quickly in the hopes of some sort of theoretical “soft” landing for the economy.

Now, to keep downward pressure on prices, the central bank appears committed to keeping rates high for as long as it takes. It might also fear that by not staying the course, prices could heat up again very quickly as credit loosens. Something to watch out for.

In the meantime, what it shows is that the central bank still has a lot of confidence in the banking system—or does it? While in his press conference following the Fed’s statement Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell claimed that “all depositors’ savings and the banking system are safe,” on the other hand Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told the Senate Appropriations Committee, “I have not considered or discussed anything having to do with blanket insurance or guarantees of all deposits.” Instead, Yellen reiterated that under federal law, banks will only be placed into receivership if the Treasury, Federal Reserve and FDIC say that the bank is systemically risky under Dodd-Frank.

There is also the psychological aspect, which is that the Fed certainly wants you to think that it has confidence and do not wish to spook more runs on banks by suddenly doing an about face on interest rates by cutting the rate right after they said they were still hiking rates.

After the last meeting, on Feb. 1, the Fed had said, “The Committee anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time.”

Now that phraseology was adjusted in the March 22 statement, which read, “The Committee will closely monitor incoming information and assess the implications for monetary policy. The Committee anticipates that some additional policy firming may be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time.”

Meaning with inflation still at 6 percent, there’s still some ways to go to get back to 2 percent over the long haul. Much depends on how quickly the disinflation or perhaps deflation occurs, with a looming recession intervening, since that’s usually the thing that ultimately brings the inflation down anyway. By 2024, the Fed expects unemployment will be up to 4.6 percent. That implies about 2 million job losses from the current level.

But the Fed seems okay with that. In his press conference following the statement, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell explained that more firming would mean: “our decision was to move ahead with a 25-basis-point hike and to change our guidance, as I mentioned, from ongoing hikes to some additional hikes may be—some policy firming may be appropriate.”

When asked “Does firming imply a rate increase per se, or could policy firm without you increasing rates?” Powell clarified he is referring to the Federal Funds Rate, “No, I think it’s meant to refer to our policy rate.”

The financial journalists in the room were clearly concerned that the Fed’s hiking of interest rates was responsible for the banking system issues, with another question directly posed, “Do you have concerns that the recent—that the hike you did today could further exacerbate the problem in the banks?”

To which, Powell replied, “No, I mean, we’re—with our monetary policy, we’re really focused on macroeconomic outcomes.” By that he means, the inflation rate and the unemployment rate. In his opening statement, Powell restated the central bank’s statutory mandate is maintain stable rates of inflation and maximum employment for as long as possible, “The Fed’s monetary policy actions are guided by our mandate to promote maximum employment and stable prices for the American people. My colleagues and I are acutely aware that high inflation imposes significant hardship as it erodes purchasing power, especially for those least able to meet the higher costs of essentials like food, housing, and transportation. We are highly attentive to the risks that high inflation poses to both sides of our mandate, and we are strongly committed to returning inflation to our 2 percent objective.”

Now, this part may be a slight exaggeration. The Fed did not seem at all concerned with inflation all throughout 2021, even after it popped above 5 percent in June 2021 after more than $6 trillion was spent, borrowed and printed in response to the economic lockdowns, production halts and the temporary spike in unemployment as 25 million Americans temporarily lost their jobs.

The M2 money supply increased dramatically from $15.3 trillion in Feb. 2020 to a peak of $22 trillion by April 2022, a massive 43.7 percent, leading to the inflation spike.

In fact, by the time Russia invaded Ukraine in Feb. 2022—further worsening global supply issues—and critically, before the Fed had even begun hiking interest rates, consumer inflation was already north of 7.5 percent. Consumer inflation ultimately reached 9.1 percent in June 2022, where it appears to have peaked for this business cycle.

In other words, the Fed was caught off guard by how quickly consumer demand recovered, and yet, after more than $6 trillion was printed to boost demand during Covid, plus the fact that production was halted via economic lockdowns and people were paid not to work, it was literally too much money chasing too few goods. Shouldn’t they have anticipated the inflation?

And now, the central bank might be behind the curve on how in danger banks truly are with higher interest rates, with the New York Times’ Jeanna Smialek questioning the Fed’s credibility, asking, “how can the American people have confidence that there aren’t other weaknesses out there in the banking system given that this one got missed, as you noted?”

Good question, but Powell held firm in his belief that banks that had hedged against the Fed’s widely broadcast interest rate hikes should be fine, even with the higher rates. The ultimate answer might come when we find out whether depositors and critically stockholders of banks agree.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.