“You just can’t. No one’s ever tied them together before.”

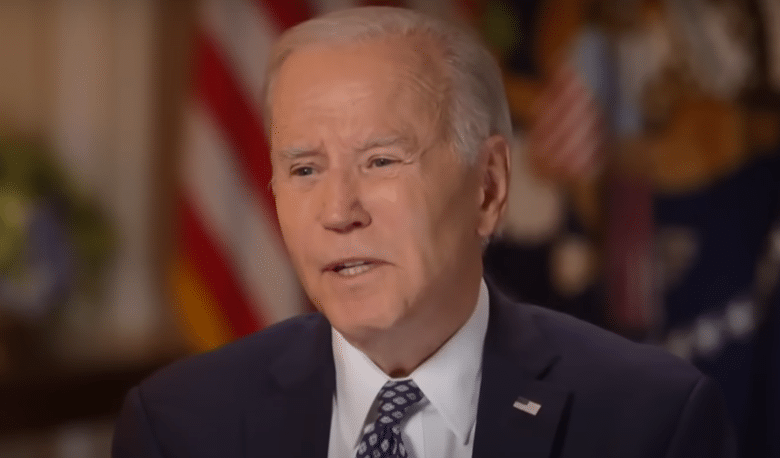

That was President Joe Biden on MSNBC on May 6, claiming that Congress has never increased the debt ceiling in exchange for budget, spending and regulatory changes.

There’s only one problem. It’s completely false.

Just in recent history, both the Budget Control Act of 2011 and the Contract With America Advancement Act of 1996 resolved disagreements between Congress and the president over raising the national debt ceiling. Both bills made changes to law to restrain the growth of spending or to pass other regulatory reforms.

Particularly, the Budget Control Act of 2011, or S.365 — the result of a compromise between then-House Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) and President Barack Obama — set discretionary budget limits into law, increased the debt limit and even provided for the consideration of a balanced budget amendment.

Title I was the “Ten-Year Discretionary Caps With Sequester.” Title II was the “Vote On The Balanced Budget Amendment.” Title III was the “Debt Ceiling Disapproval Process.” Title IV was the establishment of the “Joint Select Committee On Deficit Reduction.” And Title V was the “Pell Grant And Student Loan Program Changes.”

The legislation at the time was projected by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to reduce the deficit by $917 billion from 2012-2022: $741 billion from the discretionary spending caps or sequestration, $20 billion from reductions to mandatory spending and $156 billion as a result of less interest payments owed thanks to cutting spending.

In describing the bill which he signed, which increased the debt ceiling, then-President Obama stated in Jan. 2012, “we have to renew our economic strength here at home, which is the foundation of our strength around the world. And that includes putting our fiscal house in order. To that end, the Budget Control Act passed by Congress last year — with the support of Republicans and Democrats alike — mandates reductions in federal spending…”

Biden should know. He was the White House’s lead negotiator on the Budget Control Act of 2011. Politico’s Glenn Thrush, Manu Raju, John Bresnahan and Carrie Budoff Brown even wrote a glowing piece about it in Aug. 2011, “Biden, McConnell and the making of a deal,” which described Biden’s role: “[The] account of the final days of high-stakes negotiations is based on interviews with lawmakers, congressional staff, administration aides and Democratic officials familiar with the talks. They described an agreement sealed by Obama and Boehner but said it was Biden’s close working relationship with McConnell that broke the months-long logjam.”

As for the 1996 Contract With America Advancement Act, that also increased the debt ceiling and included the Congressional Review Act, the Line Item Veto Act, the Senior Citizens’ Right to Work Act and the Small Business Growth and Fairness Act of 1996.

Both times, these situations arose from a Republican takeover of the House and/or Senate following a Democratic president’s first Congressional midterm election.

So, just in recent memory, this is not the first time nor the second time, but the third time this process has come up with Congress sitting down negotiate with the White House on the terms and conditions for increasing the national debt ceiling, currently at $31.4 trillion.

In both cases, the appearance of fiscal discipline helped out both former President Bill Clinton and former President Barack Obama, who both went on to get reelected in 1996 and 2012, relatively easily.

H.R. 2811, the Limit, Save, Grow Act of 2023 — which has already passed the House — would increase the national debt ceiling and cut $4.8 trillion in deficits through 2033: $3.2 trillion from the discretionary spending caps, $460 billion from ending President Biden’s student loan forgiveness program, $569.5 billion from repealing the green energy subsidies from the Inflation Reduction Act and other legislation, $120.1 billion from implementing work requirements for food stamps and other welfare programs, $29.5 billion from budget rescissions from Covid and other spending, $3.4 billion from energy leasing and permitting provisions and $547 billion as a result of less interest payments owed thanks to cutting spending.

Now, Biden might prefer that these items be dealt with separately under regular order of the budget process, but that is not the hand he is being dealt. The House has already passed H.R. 2811 and 43 Senate Republicans have vowed to oppose increasing the debt ceiling without spending cuts.

Meaning, Biden doesn’t have the votes in the Senate to overcome a filibuster in order to increase the debt ceiling. Even if he could, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) has stated on April 26 then the legislation would go to a conference committee, as provided under House and Senate rules, in order to reconcile differences.

Either way, the Limit, Save, Grow Act is the only game in town, that is, besides other unconstitutional suggestions like President Biden somehow increasing the debt ceiling under the 14th Amendment’s “The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law… shall not be questioned.”

For Biden’s part, he stated “I’ve not gotten there yet…” in the MSNBC interview.

This was followed up by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on ABC’s This Week on May 7 stating, “We should not get to the point where we need to consider whether the president can go on issuing debt. This would be a constitutional crisis.”

Yellen is right. It would be a constitutional crisis, because it’s unconstitutional. The only public debt “authorized by law” is that presently subjected to the $31.4 trillion debt ceiling under current law. But if Biden is feeling lucky, perhaps he could try this newly minted theory of constitutional law out on the 6 to 3 Republican-appointed majority on the Supreme Court, all the while bearing the consequences economically for refusing to negotiate with Congress when that is the situation with ever piece of legislation that comes up.

Biden again might prefer an alternative to this process but so far he hasn’t really articulated one. Either way, this is the process that has been used historically in cases of mixed government, where neither party completely controls the House, Senate and White House, including 2011 and 1996, and has in fact resulted in bipartisan compromises that both increase the debt ceiling, reduce deficits and make other changes to law.

They’ve always been “tied together,” Mr. President.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.