Sept. 30 has come and gone as fiscal year 2023 has ended, but without an agreement from Congress on appropriations for the $1.7 trillion so-called “discretionary” budget, resulting in a 45-day continuing resolution that will continue to fund the government at 2023 levels, give or take, until Congress later hammers out a more permanent agreement.

What else is new?

This is what usually happens every year, regardless of which party is in power, with some variation: the fiscal year will be coming to an end and, with or without a government shutdown, eventually Congress will pass a continuing resolution for a month or two, as the appropriations committees in the House and Senate hammer out a year-end omnibus spending bill or continuing resolution.

In fact, since 1977, Congress has completed all of its appropriations bills — now 12 — only four times prior to Oct. 1: in 1977, 1989, 1995 and 1997. The last time no continuing resolution was used by Congress was in 1997. Otherwise, Congress typically does not get the appropriations process done, about 91.3 percent of the time, instead resorting to stopgap spending bills in lieu of a massive omnibus or year-long continuing resolution.

The gridlock is by design, with the Constitution providing for a bicameral legislature that often is composed of opposing parties who must find agreement with the President, who also might be of a different party, for any bill including appropriations to become law. Situations of there being mixed party rule occurred most of the time since 1977, 66 percent of the time, whereas only 33 percent of the time was there one-party control of the House, Senate and White House, 1977 through 1980, 1993 through 1994, 2003 through 2006, 2009 through 2010, 2017 through 2018 and 2021 through 2022.

Ironically, three out of four times that Congress got all of its appropriations bills done prior to Oct. 1 came with mixed party situations, where one party controlled the White House and the other controlled the House and Senate. In 1989, Republican George H.W. Bush came to agreement on funding bills with a Democratic controlled Congress, and in 1995 and 1997 Democrat Bill Clinton came to an agreement on spending bills with a Republican controlled Congress. In 1977, it was done with Democratic one-party rule, but that appears to be the exception.

Otherwise, the government has been funded for at least part of the year via continuing resolutions in 42 out of 46 years since 1977. These usually result in omnibus spending bills — with 29 omnibus spending bills adopted since 1986, and 15 full-year continuing resolutions since 1977 — highlighting Congress’ usual practice of combining all of the spending into one or two bills and passing them that way, rather than the supposed “traditional” 12 appropriations bills that almost always never get all done.

The other certainty is that Congress will eventually end any temporary disagreement over keeping the government funded through government shutdowns — there have been 22 shutdowns since 1976 — with the longest shutdown occurring for 35 days in 2018 and early 2019. The second longest shutdown was in 1995 and 1996 of 21 days.

Therefore, the gridlock and disagreement surrounding funding bills — and the occasional government shutdown — is not the exception, but rather the rule to expect in Washington, D.C., regardless of which parties are in power. And again, that is by design. With Congressional elections every two years, plus the bicameral constitution of Congress, and therefore the high likelihood of mixed government, the odds are almost always greater that there will be no agreement on spending. It’s supposed to be hard.

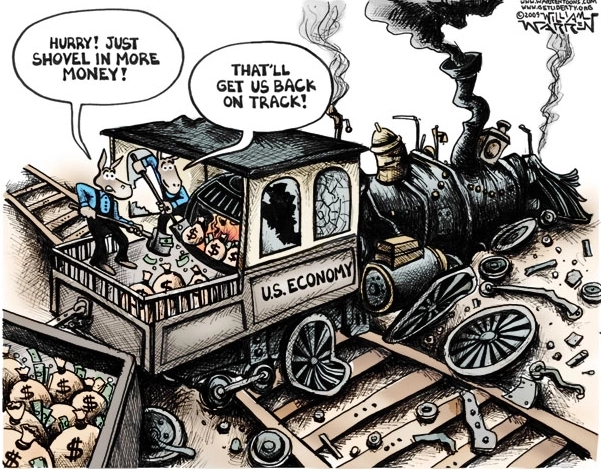

And the outcomes, with only minimal changes to baseline spending occurring, for example in 2011 and 2023 spending deals that created budget sequestration, should not be that surprising. With very little agreement about how to deal with the spending Congress has the most control over, there is even less agreement about what to do about the auto-pilot so-called “mandatory” spending — Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, interest on the debt and so forth — that occurs whether Congress does anything or not.

Without any significant changes to baseline spending, particularly with Social Security and Medicare growing by leaps and bounds this decade amid the Baby Boomer retirement wave, as a result, the Office of Management and Budget projects that by 2033, the national debt will be over $50 trillion, and that might be a low ball.

In truth it could be much larger than that, since the debt has been growing at more than 8 percent a year on average since 1980. In fact, if it continues at its current clip, it will rise to more than $100 trillion by 2037, a potential reckoning and yet, one that appears no more likely to foster agreement among the parties in Congress over what to do about it, no matter how bad it gets. Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.