The unemployment rate rose to 3.9 percent in October, reflecting 348,000 fewer people reporting they had jobs in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ household survey and an additional 146,000 saying they couldn’t find work to 6.5 million.

416,000 left the labor force altogether as the labor participation rate dipped to 62.7 percent amid continued demographic shifts of the aging population, but also individuals giving up on looking for work altogether.

Job losers increased 201,000 to 3.06 million, and part-time for economic reasons increased by 218,000 to 4.3 million. Those are worrisome indicators.

The news comes as unemployment continued claims have increased by 529,000 since Sept. 2022 to 1.8 million, according to Department of Labor data, returning to recent highs seen earlier this year.

The number of unemployed tends to rise towards the end of the business cycle as the economy overheats and inflation drops, reflecting cooler consumer demand, periodically resulting in recessions.

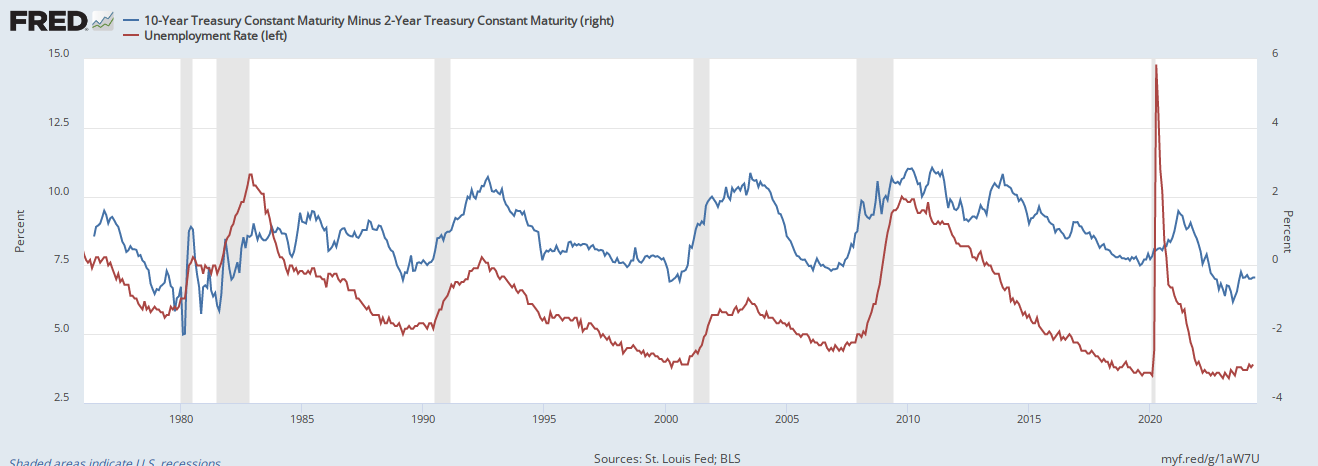

A good indicator to watch is the spread between 10-year treasuries and 2-year treasuries. When it inverts and goes negative, that usually predicts peak labor market conditions and then when it uninverts, it predicts rising unemployment rates.

Well, after a deep inversion in 2022 and 2023 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, down to a -1.08 percent low in June 2023, the spread is almost normalized at -0.31 percent. When it uninverts, perhaps into 2024, that is usually when labor markets experience the most upheaval.

All of which is terrible news for President Joe Biden, who is running for reelection in 2024, and might have to deal with twin maladies of higher unemployment and sticky inflation—usually a toxic combination for incumbent presidents. Just ask Jimmy Carter, who in 1980, with high unemployment and inflation, lost in a 44-state landslide to Ronald Reagan.

If there is any good news, it is that, so far, at any rate, the Fed is projecting unemployment to continue to rise, averaging 4.1 percent in 2024, a mild upheaval in labor markets, with a few hundred thousand more jobs lost. It’s nearly there.

And, in Biden’s case, it might have been avoidable, who, by the time he came into office, Congress had already borrowed and the Federal Reserve printed trillions of dollars for Covid, and 16 million of the 25 million jobs lost to Covid had already been recovered, opted for another $1 trillion stimulus and trillions more of borrowing and printing. Biden could’ve tapped on the brakes, but he didn’t.

All told, nearly $7 trillion was printed for Covid after the M2 money supply increased peaked at $22 trillion in April 2022, 43.5 percent above its $15.35 trillion mark in Feb. 2020 right before Covid shut down the global economy.

Now, the juice from the stimulus is gone, the money supply is decreasing, inflation has cooled from its June 2022 9.1 percent peak, and peak employment appears to be in the rear-view mirror. Is the inevitable correction dead ahead? Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.