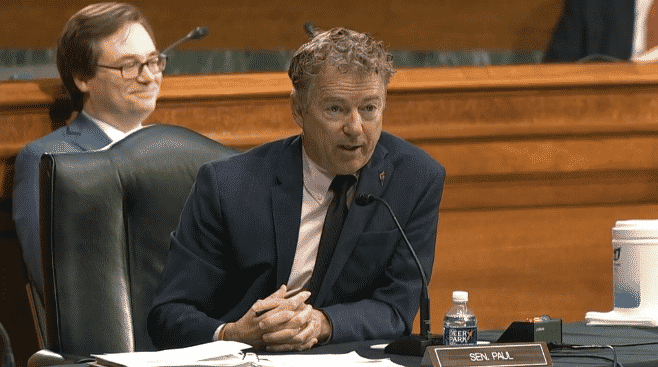

Legislation offered by Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), the “Federal Reserve Transparency Act of 2024,” would conduct an audit of the U.S. Federal Reserve by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) for the first time since the Dodd-Frank legislation of 2010 required an audit of the central bank’s purchases of mortgage-backed securities.

This time around, the GAO would look at the Fed’s entire balance sheet, including the recently enacted Bank Term Funding Program — now $141 billion according to the central bank’s latest H.4.1. release — that has been lending banks money in exchange for U.S. Treasuries after the spike in interest rates caused there to be a reported $620 billion of unreported losses including regional banks that experienced failures in the interest rate crunch.

According to Sen. Paul’s press description of the legislation the GAO will be a full audit and include “Transactions for or with a foreign central bank, government of a foreign country, or nonprivate international financing organization; Deliberations, decisions, or actions on monetary policy matters, including discount window operations, reserves of member banks, securities credit, interest on deposits, and open market operations; Transactions made under the direction of the Federal Open Market Committee; Discussions or communications among or between members of the Federal Reserve Board and officers and employees of the Federal Reserve System related to the actions listed above.”

In the context of the Bank Term Funding Program, the audit will reveal which banks have been dependent on the Fed to avoid losses due to overexposure to U.S. Treasuries — $26.9 trillion out of the $34 trillion national debt is publicly traded.

By 2033, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) estimates that the total national debt will rise to more than $50 trillion.

In reality, it could be even worse than that. Since 1980, once recessions and wars have been factored in, the debt has been growing by about 8 percent a year. At that rate, it could hit $100 trillion by 2037 or so.

All of which raises the troubling questions: Who’s going to buy all of that debt over the next couple of decades? And at what interest rates?

The last time an audit was conducted, it was revealed of the $1.25 trillion of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) bought by the Fed during the financial crisis, foreign entities sold some $442.7 billion of their mortgage securities to the Fed. Now, the Fed holds some $2.4 trillion of MBS. Who did they buy those from? An audit will say.

Particularly examining the impacts of the Bank Term Funding Program is important from Congress’ perspective, as it plans Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid spending, which is ballooning. In just the next decade, OMB reports that Social Security will rise from $1.3 trillion to $2.4 trillion, Medicare from $821 billion to $1.8 trillion and Medicaid from $608 billion to $926 billion.

As a result, the annual deficit from $1.7 trillion annually to $2.5 trillion by 2033, and the amount that will need to be funded by Treasuries markets will rise from $1.65 trillion to $2.03 trillion by that time.

Therefore seeing how overexposure to treasuries is already impacting banks — and to what degree — is particularly important. Of the current $26.9 trillion publicly traded debt, $4.7 trillion is held by the Federal Reserve and $7.4 trillion is held by foreign central banks and financial institutions, leaving $14.8 trillion for U.S. financial institutions, pension funds, institutional investors and the like.

In the recent interest rate crunch, although the current net account for the Bank Term Funding Program is $141 billion, how many treasuries have flowed through it on a gross basis?

What if a decade from now we once again experience high inflation, necessitating higher interest rates, leading to another interest rate crunch? Shouldn’t we examine how that is occurring, and to what impact, before the debt reaches, say, $50 trillion or $100 trillion?

Only an audit of the Federal Reserve can answer these questions, and thankfully, Sen. Rand Paul is still willing to ask them.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.