The Federal Reserve released the minutes of its most recent minutes of its July 30 and July 31 meeting it is ready to begin cutting interest rates to deal with rising unemployment, with the central bank reporting, “The staff’s outlook for growth in the second half of 2024 had been marked down largely in response to weaker-than-expected labor market indicators.”

The opening is being created by inflation expectations easing: “The staff’s inflation forecast was slightly lower than the one prepared for the previous meeting, reflecting incoming data and the lower projected level of resource utilization. Both total and core PCE price inflation were expected to decline further as demand and supply in product and labor markets continued to move into better balance; by 2026, total and core inflation were expected to be around 2 percent.”

As a result, “Policy expectations, however measured, pointed to a first rate cut at the September FOMC meeting, at least one more cut later in the year, and further policy easing next year.”

Which is what the central bank usually does as inflation eases and unemployment rises, which it has, by 1.47 million since Dec. 2022. In the entire post-World War II era, every single Fed interest rate cut cycle coincided with a recession. Sometimes, the recession would already be happening, like in 1957, 1970, 1974, 1980 and 1981 recessions, and other times, the rate cuts began ahead of the recessions of 1960 (which carried over into 1961), 1990, 2001, 2008 (which carried over into 2009) and 2020.

But, rest assured, they all wind up in the same place. When unemployment peaks, the Fed stops cutting rates and the cycle begins anew. At this point, we’re still at the peak interest rate part of the cycle that precedes recessions. Other recession signals, besides the rising unemployment, include the inversion of the spread between 10-year and 2-year treasuries.

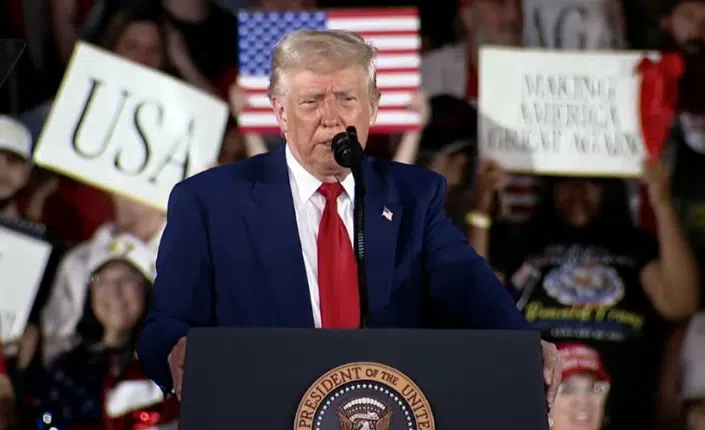

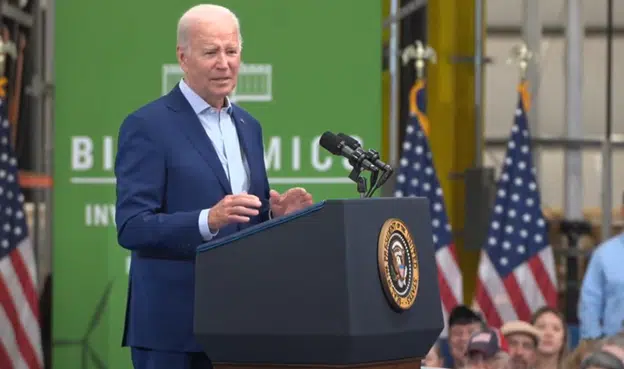

Now, all of that is usually troubling news for incumbent administrations, with recessions having occurred in terms of the incumbent parties, including Herbert Hoover losing in 1932, Vice President Richard Nixon losing in 1960, Gerald Ford losing in 1976, Jimmy Carter losing in 1980, George H.W. Bush losing in 1992 and Donald Trump losing in 2020.

Sometimes, the incumbents win another term in spite of recessions during their terms, including Lyndon Johnson in 1964, Richard Nixon in 1972, Ronald Reagan in 1984, George W. Bush in 2004 and Barack Obama in 2012.

So, overall, when there’s a recession the incumbents have lost 54 percent of the time. If one wishes to remove 1964 and 2012 from that, owing to the recessions beginning before John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson’s and Obama’s terms of office, respectively, then that’s six losses to three wins, and the incumbents lost 67 percent of the time.

But some of those losses — Hoover in 1932, Nixon in 1960, Ford in 1976 and Bush in 1992 — came after the incumbent party had already been in power for two or more terms, when statistically the probability of winning another four years for the ruling party drops markedly regardless of economic conditions.

Leaving only first term administrations with recessions that began while in office, then, the losing years include 1980 and 2020. And the winning years remain 1972, 1984 and 2004. Three wins, two losses.

So, for first-term incumbents in modern history with recessions that began after taking office, they won another term 60 percent of the time, and lost 40 percent of the time. Otherwise, incumbent parties in their first terms win re-election 66.6 percent of the time and lose 33.3 percent of the time over U.S. history.

For former President Donald Trump — who was one of those first-term presidential economic victims — that could potentially be good news in his bid against Vice President Kamala Harris, even if it only improves the odds marginally.

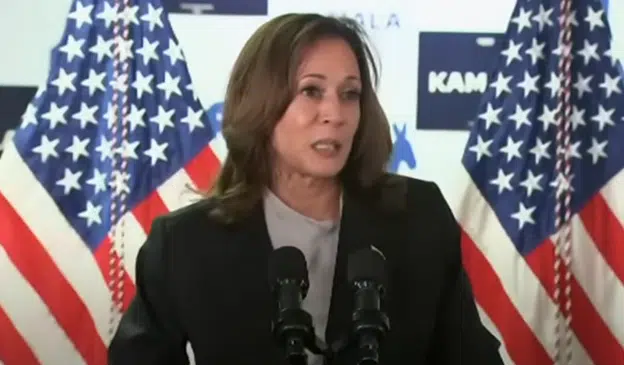

Mostly because most Americans think we’ve been in a recession for some time now. In May, Harris did a poll for the Guardian that showed 55 percent of voters think we’re already in a recession, including 67 percent of Republicans, 53 percent of independents and 49 percent of Democrats.

That was way up from May 2023 when Harris asked the same question, when 37 percent said the U.S. was in a recession and another 42 percent said we would be so in the next year. Only 21 percent though a recession would be avoided. That could make 2024 a toss-up.

Meaning, voter attitudes are already economic pessimistic. That could hurt Harris in November, who will have to choose between attempting to persuade most Americans that there is no recession and that the economy is strong, or acknowledging the current weakness, which includes inflation outpacing personal incomes since Biden and Harris took office. Or maybe even worse, saying nothing about the problem, hoping it all goes away and taking her chances at the polls in November. Stay tuned.

Correction: 1976 was incorrectly stated as a first-term incumbent party administration losing when calculating the headline number of first-term incumbent parties, but Gerald Ford, a Republican, was serving Richard Nixon’s second-term. There were five first-term incumbent party administrations wherein a recession began after taking office in modern history: Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush and Donald Trump. Nixon, Reagan and Bush won reelection, while Carter and Trump lost, bringing the reelection rate to 60 percent for those unique cases, not 50 percent.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.