As I stared at my computer screen full of facts, figures, links, and letters about the moral hazards of American investments in Chinese companies, I wondered how I could get people to care that their retirement pensions could be funding a vast network of concentration camps in the Xinjiang province where as many as 3 million Chinese Muslims could be imprisoned.

Not exactly click bait.

So, like any good writer, I left my office to clear my head. What happened next was totally unexpected.

As I drove through suburban Northern Virginia, a nondescript storefront caught my eye. It was a Uighur restaurant. Uighur is another name for Chinese Muslims. I couldn’t believe my luck! Standing behind the counter was a petite young woman with short black hair pushed back with an orange bandana and wearing round black-framed glasses on a makeup-less face. Her features didn’t look Chinese. She looked more like my Hispanic and Native American ancestors from New Mexico.

The restaurant was empty of customers, so I took the opportunity to ask her a few questions. I thought she might be able to put me in touch with someone from the Uighur community for my story. Very quickly I learned she herself was a Uighur who fled China with her younger sister four years ago.

In remarkably good English, she told her story.

In her country she said she could never get a job or get an education because “I am different.” When she was 19-years old, her parents got travel visas to America for her and her 16-year old sister. Both have since been granted political asylum.

Ameera did not want me to share real her name for fear that her parents back in China would be killed if the Chinese government learned she’s talking about the abuses of Uighurs in Xinjiang.

“The Chinese government will force the Muslim girls to marry a Chinese man and if they refuse, their family is threatened,” Ameera said. “In 2009 a lot of our people were killed, including some of my family’s friends and relatives. That is when my parents decided to send me and my sister away.”

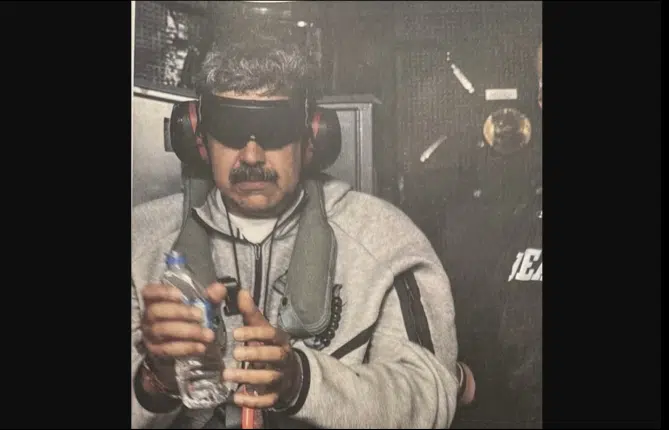

Ameera’s boss, also a Uighur, came out from the back of the restaurant and joined in the conversation. Asim (not his real name) said he had a brother who had traveled to Mecca once to fulfill his religious obligations as a Muslim. Asim said fifteen years after his travels, the Chinese government questioned him about it and threw him in prison. “Many of us are taken to prisons, and the Chinese do terrible things to us. When my brother came out of that prison, he was sick for a long time. Everyone who is in those prisons gets sick, no one knows what it is. But they die.”

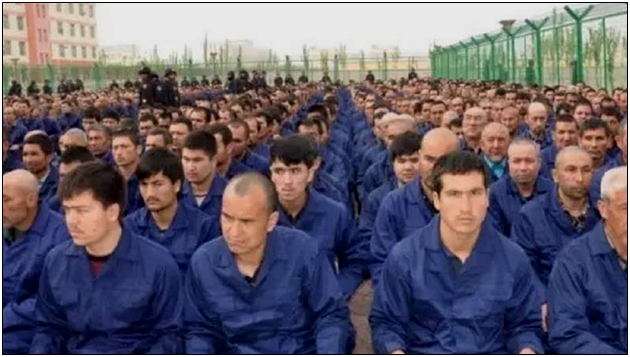

Asim’s brother was one of an estimated 3 million Muslims imprisoned in the vast network of Chinese concentration camps. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Asian and Pacific Security Affairs Randall Schriver recently told a Pentagon briefing, “The [Chinese] are using the security forces for mass imprisonment of Chinese Muslims in concentration camps,” justifying the use of the term because “given what we understand to be the magnitude of the detention, at least a million but likely closer to three million citizens out of a population of about 10 million”.

The Chinese government surveilles these concentration camps using cameras provided by a company called Hikvision, one of many Chinese companies that U.S. pension funds are invested in. In total, American pension and mutual fund holders and other investors have put more than $381 billion in Chinese and Hong Kong companies’ equities and bonds held overseas, according to U.S. Treasury data. Many of these companies engage in child and slave labor according to an annual report on child and forced labor by the Department of Labor Bureau of International Labor Affairs.

“Unwittingly, American pensioners are parties to and profiteers from the exploitation of the victims of such cruel abuse,” wrote Rick Manning, President of Americans for Limited Government, in a letter earlier this month to state treasurers, comptrollers, and governors. Manning is part of a national coalition urging federal and state authorities to rid their pension funds of Chinese investments, to delist Chinese companies from U.S. exchanges and to have the Department of Labor deem that non-transparent Chinese state-owned companies are unsuitable for 401(k) and other pension investments under ERISA.

In May, that coalition succeeded in getting the Trump administration to immediately halt all investing of federal Thrift Savings Plan (TSP) assets in Chinese companies. The TSP is a retirement savings and investment plan for federal employees and members of the uniformed services.

Steve Alberts, 50, a real estate broker in Williamsburg, Virginia recently took a closer look at his state pension fund to determine if he was invested in Chinese companies. “After the whole Covid virus from China, I said, ‘I’m through. I’m done with buying anything from them.’”

Alberts said as he searched through the various investment indexes in his fund, he had a hard time figuring out what he was looking at. “It’s not easy trying to figure out what all the three-letter codes are. I want to know where my money is invested because it could come crashing down,” Alberts said. “If it is in volatile foreign investments, I don’t want it.”

Alberts went on to explain, “This is not a right-wing conspiracy. I don’t want to support the slave labor market for tennis shoes and iPhones. I don’t want to hear this is xenophobic. I simply don’t like my money being invested in companies that don’t follow the same code of ethics that I do.”

Back at the Uighur restaurant, I tried explaining to Ameera and Asim about the story I was writing. They both immediately understood the implications of U.S. investments in China and were pleased Americans are taking steps to divest. “We like that Trump is getting tough with China.”

As I left, I wanted to make sure I had understood Ameer correctly when she told me she’d never see her parents again. “Ever, ever?” I asked. Her eyes began to well with tears. “I will never see them again.” Ignoring Covid cautions, I hugged her. What else was I to do?

Catherine Mortensen is the Vice President of Communications at Americans for Limited Government.