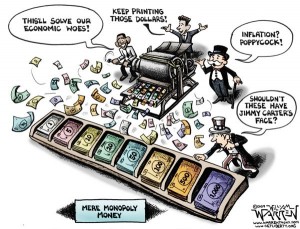

The practice of printing money or inflating a currency to “pay” for a national debt has been around for at least as long as the practice of governments borrowing funds to pay for their unsustainable obligations.

Economist Adam Smith noted this sort of trickery by governmental authorities in 1776 in his tome, The Wealth of Nations: “The raising of the denomination of the coin has been the most usual expedient by which a real public bankruptcy has been disguised under the appearance of a pretended payment.”

Which is exactly what countries are doing today. In the U.S., the Federal Reserve holds $1.66 trillion, or 10.6 percent of the $15.6 trillion national debt. That is an increase from about 7.5 percent of the debt in 1996.

Throughout the rest of the world, things are not much better. The Bank of Japan (BOJ) holds about ¥66.1 trillion ($797 billion) of its country’s ¥958.6 trillion ($11.6 trillion) debt, or about 6.8 percent of the total.

That’s slightly misleading, however, because Japan’s debt is already more than twice the size of its ¥468.4 trillion ($5.65 trillion) economy. BOJ’s holdings of Japanese debt as a 14.2 percent share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is actually larger than the Fed’s of U.S. debt at 10.8 percent.

BOJ is continuing to expand its pot of government debt with even more programs, including a new purchase this year of ¥10 trillion ($120 billion). This comes in addition to its regular purchases of about ¥21.6 trillion ($260.7 billion) every year. “It looks like they have crossed the Rubicon,” said Eiji Hirano a form BOJ executive director of international affairs from 2002 to 2006. That’s putting it mildly.

In Europe, continental authorities there too have increasingly resorted to unadulterated, outright monetization of its debts. Previously thought to be prohibited by the Lisbon Treaty, the European Central Bank (ECB) too has crossed its own Rubicon to deal with the budding sovereign debt crisis in Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain (PIIGS).

Total eurozone debt is about €10.2 trillion ($13.6 trillion), of which the ECB already holds €218 billion ($290.8 billion), or only about 2.1 percent. But they’re just getting warmed up. That does not include more than €1 trillion of kick-the-can low interest refinance loans to banks so they have the money to continue to lend to bankrupt governments.

We do the same thing here, where the Fed lends to financial institutions at near-zero interest rates, allowing them to participate in treasuries auctions, currently earning 2 percent on 10-years. The difference with Europe is it has just gotten in on the act after swearing it never would when the eurozone was founded.

It may not be enough. Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti is warning that systemic risk on the continent may be spreading to Spain, saying, “It doesn’t take much to recreate risk of contagion… [Spain] hasn’t paid enough attention to its public accounts.” He’s not kidding.

The slightest surprise — in this case Spain announcing at the end of last year its deficit would be larger than expected — increases the continent’s funding needs by hundreds of billions of euros. Since that gap is not being filled by private funding, it must be filled by the ECB.

Again, none of this is certainly new, but on a large scale this is the future of governmental fiscal policy. It will increasingly be financed through credit expansion by central banks.

But this poses a serious challenge to fiscal reformers in any nation that partakes in such a scheme. Namely, what need is there to cut spending or balance budgets if central banks can just print new money to refinance existing obligations?

It’s more of a vexing problem than at first glance. One can argue that the larger government debt becomes, the slower the economy grows, as economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff have recently. Or, anyone can plainly see the chaos in Europe and know what might happen here if there is ever a funding crisis on a large scale.

But the financial elites have a trump card. If the central banks ever were to stop printing money to refinance governmental (and other) debts, the entire global financial system would collapse like the house of cards that it is, inflicting massive pain on all parties. It’s mutually assured destruction.

All of which leaves reformers — and taxpayers responsible for making interest payments on ever-larger sums of debt — in a proverbial no-man’s land. Governments dare not cut spending.

When one asks why the House Republican fiscal plan, which would not balance the budget until 2040 according to the Congressional Budget Office, is so tepid, this is why.

It’s the “new” normal.

Bill Wilson is the President of Americans for Limited Government. You can follow Bill on Twitter at @BillWilsonALG.