If a president cannot be prosecuted by the Justice Department while in office for potential crimes committed in the process of executing official acts of the Presidency, because doing so would unconstitutionally interfere with the separation of powers and the execution of the office, can he be prosecuted after he leaves office?

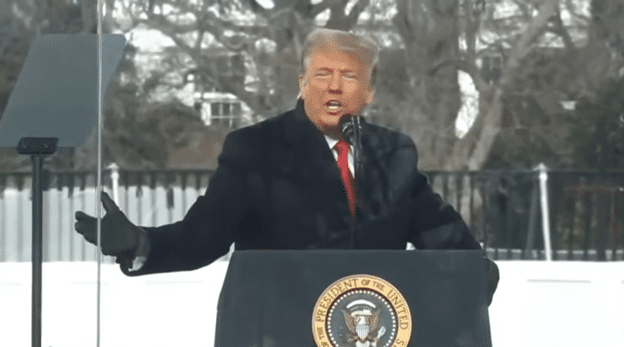

That is what the Supreme Court will be deciding as it heard oral arguments on April 25 in the Trump v. United States case on presidential immunity as it relates to potentially official acts by former President Donald Trump when he challenged the results of the 2020 election while still in office, including urging Congress to reject the electors of Arizona, Pennsylvania and Georgia.

On Dec. 1, 2023, U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan dismissed Trump’s claims of presidential immunity as a former president, saying that former presidents could be prosecuted even for official acts while in office: “Whatever immunities a sitting President may enjoy, the United States has only one Chief Executive at a time, and that position does not confer a lifelong ‘get-out-of-jail-free’ pass. Former Presidents enjoy no special conditions on their federal criminal liability. Defendant may be subject to federal investigation, indictment, prosecution, conviction, and punishment for any criminal acts undertaken while in office.”

Chutkan did so without any analysis about whether the acts in question were official or were private or whether the official acts in question were core powers that Congress would have no power to criminalize, it was simply a blanket denial that any analysis at all was necessary at the district court level to get the case to trial.

It raises all sorts of questions, like which official acts can a former president be prosecuted for later, if any?

Did the Framers intend for former presidents to be prosecuted after leaving office for official acts?

Did they intend to limit the question to Congress via the impeachment clause while a president was in office?

Finally, would the future threat of prosecution upon leaving office chill the functions of the presidency just as much as threats of prosecution while in office?

As it turns out, based on the more than two hours of oral arguments, those appear to be the key questions on how the case will ultimately turn. And not a bit of it was ever considered at the district court level.

In Trump’s initial brief asking for the stay on the district court’s ruling, his lawyers outlined the conduct for which he was charged that they say fell within the President’s duties, arguing he had the power to investigate claims of election fraud in 2020 and then to communicate to the executive branch, the legislative branch and the states his position on those questions.

First, addressing the federal indictment, Trump says he communicated using official channels “matters of paramount federal concern” with his election fraud allegation: “using official channels of communication, made a series of tweets and other public statements on matters of paramount federal concern, contending that the 2020 federal election was tainted by fraud and irregularities that should be addressed by government officials.”

Second, Trump also communicated these concerns to the Justice Department: “President Trump communicated with the Acting Attorney General and officials at the U.S. Department of Justice—which he oversaw as an integral part of his official duties as chief executive—about investigating suspected election crimes and irregularities, and possibly appointing a new Acting Attorney General.”

Third, Trump similarly communicated these concerns to states: “President Trump communicated with state officials about the administration of the federal election and urged them to exercise their official responsibilities in accordance with the conclusion that the 2020 presidential election was tainted by fraud and irregularities.”

Fourth, Trump communicated the same concerns to the Vice President and to Congress: “President Trump communicated with the Vice President in his capacity as President of the Senate, the Vice President’s official staff, and other members of Congress to urge them to exercise their official duties in the election certification process in accordance with President Trump’s contention that the election was tainted by fraud and irregularities.”

And fifth, then alternate slates of electors were convened for the Vice President and Congress to consider on Jan. 6, 2021: “other individuals organized slates of alternate electors from seven States to ensure that the Vice President would be authorized to exercise his official duties in the manner urged by President Trump… According to the indictment, these alternate slates of electors were designed to validate the Vice President’s authority to conduct his official duties as President Trump urged.”

Here, Trump has argued that those were all things he had the power to do as president, even if they were not all core elements of the executive’s powers, they could indeed be incident of executing them, not just in the case, but in future cases where Congress has not explicitly prohibited a president from acting in a certain way.

In this case, Trump is being charged under a broad statute not to defraud the government of the United States. Does that even apply to a president in the general execution of his official powers? And the district court never considered any of those elements.

As a result, perhaps the case might be wholly dismissed, but if not, the justices might be tempted to simply send it back to the district court to determine which of the acts alleged were official acts and which were not, before any analysis can occur about whether the indictment might proceed if it cannot include any official acts.

As Chief Justice John Roberts noted in the arguments, that could end up being a “one-legged stool,” wherein the prosecution cannot move forward if divorced from the President’s official acts. Good.

If so, presidents, present and future, and the country as a whole, might all be better off.

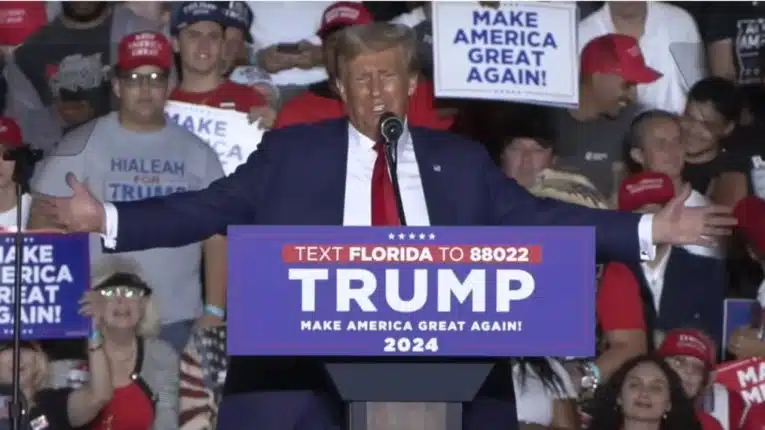

Put these questions to Congress via impeachment where they belong, which is supposed to be constitutionally difficult — no president has ever been convicted and removed from office — and take away the possibility of politically motivated prosecutors from criminalizing every aspect of the presidency going forward. Because it won’t end with Trump. This Pandora’s Box being opened will just be beginning.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.