As originally published at RealClearMarkets.com.

Markets immediately started tanking, and continued, through Aug. 2 before finally recovering on Aug. 3. Traders apparently wanted another temporary sugar high from the nation’s central bank and didn’t get it.

Oh well, not that it matters all that much.

As if the Fed taking on another $500 billion or so of federal government debt would have magically turned the economy around any more so than the previous $860 billion of such purchases since Aug. 2007 has.

To print, or not to print?

Even some more conservative pundits were distraught, such as Bloomberg View columnist Caroline Baum, usually a hawk on monetary policy, who advocated for the Fed to “consider more outright purchases of treasuries… Yes, print money. There, I said it.”

Baum wrote she is “thinking differently” about monetary policy, but has not reached any conclusions yet. What promoted her new, potential outlook was a recent book by Robert Hetzel, senior economist and research adviser at the Richmond Fed, entitled, “The Great Recession: Market Failure or Policy Failure?”

In it, Hetzel takes the view that monetary policy — even with the Fed’s gross expansion of its balance sheet from $869 billion in 2007 to $2.8 trillion today, more than tripling it in just a few short years — is too tight, and has “simply accommodated the increased demand for bank excess reserves.”

To be certain, deposits held by Federal Reserve banks on behalf of financial institutions have exploded from $13.4 billion in 2007 to more than $1.5 trillion today. Therefore, it is hard to argue with Hetzel’s conclusion that most of QE1 and QE2 is just sitting in a vault.

Probably the reason for that is as a hedge against any new losses that pop up in the wake of the financial crisis, which as Europe is discovering, may just be clearing its throat. Leaving that aside, if one views current policy as being too tight, one opens the door for more credit expansion.

But how much money-printing would be necessary to restore economic growth seen in the past 60 years?

Doubling down

Previously, Americans for Limited Government President Bill Wilson has examined the relationship between credit expansion in the U.S. and the growth of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) since World War II in a piece entitled, “Can the economy grow without debt?”

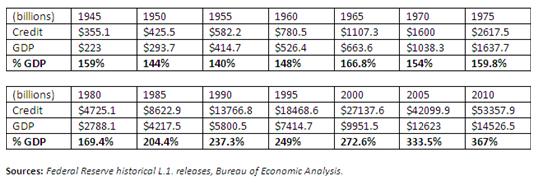

In it, Wilson observes that the relationship between debt and economic growth between 1945 and 1970 was relatively stable. Throughout that period, credit outstanding nationwide hovered between 140 to 167 percent of GDP.

But, after 1971, when Richard Nixon severed the final ties between the dollar and gold, credit exploded at a pace far faster than the economy could grow, expanding all the way to 367 percent of GDP in 2010.

That’s problematic, however, because in all previous decades, which generally saw large nominal increases in GDP, the amount of credit essentially doubled. To keep pace now, credit needs to grow by about $5.3 trillion annually.

Writes Wilson, “Whereas for 25 years we got 1 unit of growth for 1 unit of debt, today, we get 1 unit of growth for 2 units of debt. Since 2000, debt has grown at double the rate of the underlying economy. And that is where the danger and fear come in.”

Wilson continues, “If this relationship continues, we will have to have debt increases on a mind-numbing scale just to meet modest growth projections.” But, again, by how much?

Oh, about $50 trillion or so of new debt — in less than ten years. We’re nowhere near that right now. So, all of you homeowners? Go buy another home. College graduates? Go back to school for another four to eight years. In the meantime, the government can colonize the moon (and the ocean floor while it’s at it), fight a few more wars, and we might as well take on the Chinese model of building complete cities with little to no population.

Which, of course, is just silly. But how else are we going to double that much debt? In reality, it probably matters little what the money is even spent on, just that it’s spent and the credit bubble continues to grow. In essence, that is where the current model for credit expansion has taken us.

C’mon. You want the economy to grow, right? Well, we all need to do our part and instead of tightening our belts, tighten the shackles of debt around our ankles (and latch a shackle or two around the ankles of our children for good measure).

But isn’t that how we got into this mess?

At this stage, a rational observer might interject that unsustainable credit expansion in sectors like housing, education, and government is how we got into this mess in the first place.

Yet, by all appearances, perhaps the only way our economy can grow any more is for banks to produce more credit — and lots of it.

Still, there are some on Capitol Hill who appear opposed to further mindless lending.

Writing in opposition to the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial law in the Wall Street Journal, House Republican Conference Chair Rep. Jeb Hensarling of Texas called for several meaningful reforms including winding down Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and bringing an end to the bailout authority established under the statute.

Instead of more government-backed lending and bailouts, Hensarling proposes that “The way to address the risks posed by financial institutions would be more transparent balance sheets and a meaningful application of capital and liquidity standards. As long as companies have enough capital to cover their risks and absorb potential losses, we don’t need federal regulators micromanaging credit allocation.”

But what makes Hensarling think financial institutions are adequately capitalized at all?

De facto unlimited financing, an outcome produced by today’s financial system built on capital requirements — wherein, say, $100 of capital can produce $1,000 of credit by a bank — does not leave banks with much room for error, nor does it rationally allocate credit into particular asset classes like real estate or higher education.

Instead it produces housing bubbles and thousands of liberal arts degrees that do nothing to enhance employability.

Many today argue (or imply) that if lending institutions simply and merely returned to prudential lending standards, credit bubbles would not form, and all would be well. But, today, there is no real incentive to be prudent.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are purchasing or guaranteeing virtually every mortgage that moves. The higher education lending industry has already been nationalized by the federal government — perpetuating the pleasant fiction that a college education, regardless of what one studies, is an entitlement guaranteed to every American.

In short, markets are not driving credit allocation at all. Government is. Specifically, the demand for credit and government’s desire to supply it. Hence all of the calls for the Fed — and not, say, Bank of America — to fire up its printing presses to increase the supply of credit.

The sinking city

Unless there is a constraint on that supply — i.e. an inability to lend credit into existence by government and financial institutions — demand for credit will continue to drive an irrational, excessive buildup of debt. That is, to the extent anyone can even afford to leverage up further even at today’s low interest rates.

But, should we find a way to get credit expansion moving forward again, financial institutions will remain woefully undercapitalized to absorb market downturns, resulting in periodic bailouts and further expansions of central bank balance sheets along with sovereign debt.

The entire edifice is built on a sinking foundation — which is the false assumption that continued credit expansion will facilitate sustainable economic growth. But we know now it is not sustainable.

Monetary easing, credit expansion, and other forms of “stimulus” may produce temporary sugar highs. But in the long-run it produces ghost towns where hardly anyone lives in Nevada, Arizona, Florida and elsewhere, and college graduates with student debts far in excess of the market value of their gender studies degrees (i.e. the graduate’s ability to repay with the skills that were acquired in said education).

What to do?

Hard money would never produce such irrational outcomes. There would not be enough credit to accomplish such a mess. Instead, if unlimited financing for college was unavailable, parents would respond by saving more for their children’s education or students would simply work to pay their way through — and tuition rates would drop since demand would be less.

Banks would respond to less credit by requiring greater down-payments in order to purchase a home. Home prices would also fall even further, mitigating the need for so much credit to get a home in the first place.

That is because you cannot have hard money and have asset prices — along with the value of assets on banks’ balance sheets — remain as high as they are.

For now, the creation of new debt is already constrained, because credit itself, with an aging population, has already reached or is close to its maximum serviceable levels. This is hitting the middle class hard in a deflationary trap of increasing negative equity and even more defaults.

To get through this, with more than $54 trillion of credit nationwide to be serviced, the current debt overhang still needs to be worked through and stabilized as a percent of the economy — 150 percent of GDP appeared to work fine for 25 years after World War II — before it can begin to increase on a nominal basis again. The question is how.

Restoring value

As a nation, we have a choice. The only way out of this mess is to either: a) double outstanding credit once again this decade (and accept all of the irrational outcomes that are produced, and the inevitable bailouts to follow) and continue to devalue the dollar; or b) return to sound money and reduce overall debt through repayment.

We opt for the latter. We need to restore value, not just to assets or the dollar, but to productivity.

To keep our high standard of living, we need to be in a situation where income and savings are sufficient to acquire basic staples (food, housing, energy, transportation, etc.) that make living in America so great — but also for existing debtors to be able to pay off their debts. Low inflation on its own will make most forms of credit unnecessary. In other words, you’ll be able to afford it.

The way to get there will not be easy, however. Leverage in the system needs to be reduced to more sustainable levels while new credit creation is restricted — and it needs to be done in a way that does not wipe out banks or leave individuals stranded, both with debts that cannot be repaid.

This will smooth the transition and prepare the U.S. for an economy based less on credit distortion, and more on the real value of goods, services, and labor.

Such a process is fraught with peril, but if handled properly, will leave the American people with a more-manageable balance sheet, greater purchasing power, and most importantly, freedom from debt.

Robert Romano is the Senior Editor of Americans for Limited Government.