Yet the interest rate on ten-year treasuries is just 1.7 percent as of this writing.

Across the Pacific, Japan has an even higher debt-to-GDP ratio of 208 percent. Its ten-year borrowing costs come in at 0.7 percent.

Comparatively, Spain has a debt-GDP ratio of just 72 percent. But its ten-year borrowing costs are 5.6 percent, having risen as high as 7.6 percent this year. It is said to be considering a bailout from the European Stability Mechanism.

If this seems counterintuitive, that’s because it is. With much higher debt-to-GDP ratios, one would expect the U.S. and Japan to have higher borrowing costs closer to, say, Greece.

Greece’s debt-to-GDP comes in at 135 percent, with an interest rate of 18.4 percent — more in line with what one might expect a bankrupt government to be charged.

Instead, it appears the deeper in debt one goes in the U.S. and Japan, the cheaper it becomes for governments to borrow. But why?

While one could examine economic differences between all of these countries, differing demographics, or unemployment rates, they do not offer an adequate explanation.

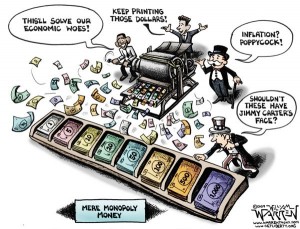

The primary reason is simply because we are cheating. Both the U.S. and Japan have accommodative, independent central banks more than willing to monetize their country’s debts regardless of the size of borrowing. This results in an expansive financial system.

In the eurozone, the European Central Bank (ECB) is prohibited from directly monetizing member debts. The Maastricht Treaty also prohibited member countries from running deficits greater than 3 percent of GDP. As countries have breached that limit, they have been more hard-pressed to secure credit.

So, in the U.S. and in Japan, there appears to be no limit to how much quantitative easing or government spending and borrowing can take place. Whereas, in Europe, the financial system was designed to limit how much could be borrowed by member states.

Another reason why the U.S. has lower borrowing costs is because the dollar is the world’s reserve currency. It is stockpiled around the world as if it was as good as gold, and used to price and settle payment of many commodities.

That makes U.S. treasuries and other dollar-denominated assets a target for investors seeking safe returns. U.S. treasuries and gold have been two of the primary beneficiaries of a flight to safety that has occurred since the financial crisis began in 2007.

So is there any limit to how much the nation can borrow?

The answer amounts to “yes, but…”

There clearly are limits to how much financial institutions and overseas creditors have to lend to the federal government, or else overt quantitative easing would not be necessary. Even with near-zero percent interest rates that allow banks to borrow practically for free from the central bank, and then use it to purchase treasuries.

But the system’s perpetuation is largely dependent on other countries’ willingness to continue to use the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. As we export our inflation abroad, triggering instability throughout the developing world, that willingness may be beginning to wane.

Without it, demand overseas for treasuries would drop and a run on dollar-denominated assets would occur. The excess supply of dollars would find its way back home, triggering hyperinflation here.

Therefore, there is a tipping point down the road where excessive debt in the U.S. will one day trigger a financial crisis — when the economic instability we export becomes too much for other nations like Saudi Arabia or China to bear. The only question is when.

The answer, of course, is to rein in our debt — before it is too late — so we never have to find out when that doomsday might be.

Robert Romano is the Senior Editor of Americans for Limited Government.