Greece was tiny, with a Gross Domestic Product just 2.5 percent of the whole Eurozone.

Besides, €30 billion was a relatively small number. And even if Greece was having trouble raising money on bond markets, there would be little ripple effect throughout the Eurozone, let alone the global economy.

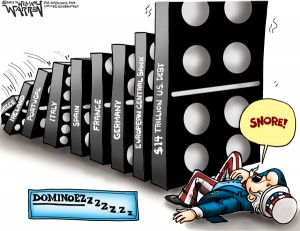

Fast-forward three years. Greece has defaulted on €100 billion ($129.1 billion), or almost one-third of its debt. Further debt crises have broken out in Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Italy. The Eurozone is once again in recession. And it is not over yet.

Now, banks in Cyprus who were exposed to Greek debt have faced serious losses and their very solvency is in question. Just an emergency liquidity lifeline from the European Central Bank keeps the economy there afloat. Banks have been ordered closed until Tuesday while policymakers scramble to figure out a solution.

So, it appears the pessimists were right about systemic risk tangled up in European sovereign debt. But why? How could a country as small as Greece’s have posed such a danger?

And why is any default by even a small government such a problem, administering contagion to the global financial system? Why does Cyprus now pose a danger, with an economy even smaller than Greece’s?

The American Enterprise Institute’s Alex Pollock has an answer. Writing on the weakening of capital requirements after the financial crisis by the Bank for International Settlements based in Basel, Switzerland, Pollock notes that “banks investing in European government debt would for such investments have zero required capital.”

Banks are normally required to hold capital against assets based on their risk. Pollock notes a zero-based capital requirement for sovereign debt “can only make sense if owning this debt has no risk whatsoever.”

But as evidenced by Greece’s default, and as highly leveraged Cypriot banks are now discovering, sovereign debt can be quite risky. And with zero capital backing that debt, the risk is all to their bottom line. Now, the potential fall of those banks may have some spillover effects of their own on the rest of the Eurozone. Why?

For starters, Cypriot banks have total assets (loans and other securities) of €126.4 billion ($163.2 billion) according to the European Central Bank. That’s 706.6 percent of its entire economy. They have as much in liabilities, including €72 billion of deposits and €32 billion of external liabilities.

But it only has €15 billion of capital and reserves. They cannot cover their liabilities should they all be called at once via a bank run.

That’s where the spillover comes into play. If depositors lose their money, they will in turn have trouble servicing their debts, creating more problems at the banks. Should the banks fail, they will be unable to service their own debts, causing losses at other financial institutions in Europe that lent them money. And so forth.

This is why it’s called systemic risk. To understand this risk, think of a row of dominoes where the fall of one leads to the subsequent fall of others.

The crisis has only been compounded by the European Union and International Monetary Fund’s boneheaded move to demand that Cyprus confiscate €5.8 billion of domestic deposits via a “one-time” tax, including those of their citizens. As if the people of Cyprus were to blame the failure of Greek bonds.

Even if Cyprus ultimately agrees to that, or another bailout, once banks are allowed to reopen, the bank run will likely ensue anyway. Trust in the financial system there has been shattered into 5.8 billion pieces amid vast public outrage.

Desperate depositors will line up in Cyprus just like George Bailey’s customers in the Christmas classic, It’s a Wonderful Life, to reclaim their life savings before either the bank shutters its doors or the government confiscates their wealth.

Once reopened, to the extent that withdrawals exceed the €15 billion of paid-in capital at the banks, they will render the banks insolvent anyway. Meaning, Cyprus will need a much larger bailout than the €10.7 billion one originally envisioned.

This is how fragile the financial system is, not just in Cyprus, but all over the entire world. It truly is a house of cards that could begin to collapse anywhere at any time. That is why losses of any kind cannot be allowed, not even in an economy as small as Cyprus’ or Greece’s.

Just look at how European heads of state and the European Central Bank have scrambled these past three years to prevent any failure of any kind in any country. If there were no need for bailouts to avert systemic risk and cascading defaults, then why does Europe time and again offer such bailouts?

That is not to say that these banks ought to be bailed out, just that it is the only way those who control the international bank cartel can keep this Ponzi system going. Without it, the entire Eurozone may be on the verge of collapse with unknown ramifications for the entire.

Still, the same smart people in the room who assured us three years ago that everything was all right are still trying to play Jedi master waving their hands saying that there is nothing to see here. That there is no crisis.

Who do you believe? After three years, the question any honest person should ask is how can the crisis in Europe have possibly been contained when a hiccup in Cyprus threatens to take the entire Eurozone?

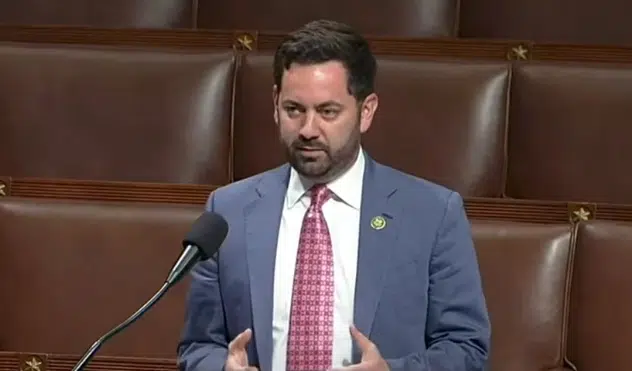

Robert Romano is the Senior Editor of Americans for Limited Government.