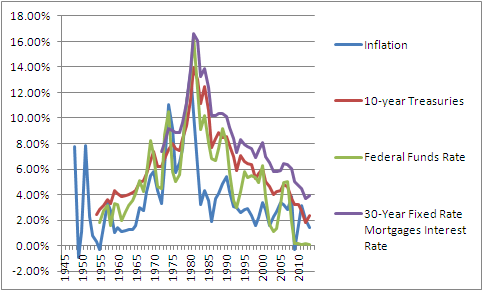

Since the great inflation of the 1970s, interest rates have been on an historic 30-year down trend — a collapse that many wonder if it will continue indefinitely.

Particularly, 30-year fixed rate mortgages peaked annually in 1981 at about 16.6 percent, hitting a bottom in 2012 of 3.66 percent, according to data compiled by the Federal Reserve.

Comparatively, 10-year treasuries hit a bottom in 2012, too, at 1.8 percent. Since then, the Fed has tapered its quantitative easing programs, from $85 billion a month of purchases to the current level of $55 billion.

Rates responded. 10-year treasuries shot up, peaking at 3 percent at the beginning of this year, but the party was not over yet. They have since dropped off, to 2.6 percent now.

Is the recent dive attributable to current events? Or is it simply continuing with the long-term trend?

Maybe both.

One might look to central bank announcements last summer that there would be no “automatic increase in [the] interest rate when unemployment hits 6.5 percent,” as then Chairman Ben Bernanke stated, referring to the central bank-set Federal Funds Rate. This indicated the Fed intended to keep bank lending rates near zero for the next few years.

This is important because drops in those rates in the past 30 years have helped mortgage rates to drop almost like clockwork. If the Fed keeps its own rates low, that should help keep rates down.

With the transition to the new Fed Chair, Janet Yellen, this has been reaffirmed, who just last week told lawmakers “we anticipate that even after employment and inflation are near mandate-consistent levels, economic and financial conditions may, for some time, warrant keeping the target federal funds rate below levels that the Committee views as normal in the longer run.”

With the Fed’s asset purchases continuing, Yellen said the central bank would “continue to put significant downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, support mortgage markets, and contribute to favorable conditions in broader financial markets.”

So, two things. The Fed still intends to keep its target interest rate near zero in the near term, and it is still buying bonds.

Couple that with a cooling market for homes led by low demand — the Federal Reserve charted an increase in the supply of homes for sale in March — and lenders may have to slash rates again to incentivize new sales.

Plus, with unemployment still high, labor participation lagging, growth weak, and conditions overseas worsening in the Pacific and still really bad in Europe, there is recipe for another flight to safety — into the welcoming arms of U.S. government bonds.

When demand for bonds increases, interest rates tend to decrease.

So, if one expects the recovery, or lack thereof, to remain on fragile footing, then it is clear that interest rates only have one place to go — and that is down.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.