“When one considers how much corruption there was in those kings, if two or three successive reigns had continued the same way, and that corruption which was in them had spread to members of the body politic, it would no longer have been possible to reform [Rome].”

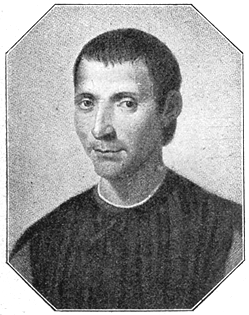

That was Niccolo Machiavelli, commenting in his Discourses on Livy published in 1517, almost 500 years ago, on what might have happened if the ancient Roman monarchy had not been overthrown by Brutus and a republic established. Although better known for his masterpiece of political violence, The Prince, here in Discourses Machiavelli’s clear preference for republican government and liberty can be found.

But, writes Machiavelli, freedom has a prerequisite, and that is virtue — a love of liberty. Lacking this virtue, then, a people become ambivalent to politics and those who wield power. Politics becomes the province of the powerful that participate, and lacking power, is something to otherwise be avoided out of fear. There are those who have access, and then there is everyone else.

If such a form of government persists for long, the freedom of the republic as a whole is ultimately lost, and the people themselves are corrupted. Not in the sense that they are accepting bribes — although public forms of subsistence duly enacted can be common in these cases to sweeten the deal of wearing a yoke — but in that inherent inability and unwillingness of the people and their representatives to affect the outcome of public decisions.

The true corruption occurs when politics only serves private or narrow interests far beyond reach, and power is concentrated into the hands of a few, and so the people only concern themselves with their private lives. This is when the people and their representatives no longer have any means of wielding true power, and thus become disconnected from the process.

Is Congress on the outside, looking in?

Today, the dust continues to settle from the Obama administration’s most recent executive action to grant unconstitutional, executive amnesty to millions of illegal immigrants without Congressional assent — and Congress’ subsequent decision to provide the public funds necessary for the executive branch to carry on its action.

Many, including this author, question openly what purpose Congress still serves, if not to make law or amend existing law. For it must be noted that this usurpation by Obama has not been limited to simply to this most recent outrage. It extends through his two terms, and through that of his predecessors.

It can also be seen in the recent move by the Federal Communications Commission to reclassify broadband Internet access as a telecommunications service under Title II of the Communications Act, after the agency had previously determined broadband to be exempt in 2002.

Congress’ response? So far, it has done nothing. Later this year, it will most likely continue to fund the agency. But the abdication really came when the agency’s broad powers to make such determinations were created by Congress in the first place in 1934.

Or it can be found in the administration decision to allow federal exchanges under the health care law to distribute insurance subsidies, when the law explicitly forbade it — an issue now before the Supreme Court. Or to postpone implementing the law’s employer mandate when no such exception was even considered under the law.

Here, in the latter example, the House of Representatives did file a federal lawsuit in 2014, but it has also abdicated along with the Senate by continuing to fund the law’s administration.

Or one could look at the prior Bush administration’s decision to apply $17 billion of Troubled Asset Relief Fund monies to troubled automakers GM and Chrysler when the law only ever allowed funds for financial institutions caught in the mortgage meltdown, and Congress had already explicitly rejected an auto bailout. Announcing his decision in 2008, then President George W. Bush said, “Congress was unable to get a bill on my desk before adjourning for the year. This means the only way to avoid a collapse of the U.S. auto industry is for the executive branch to step in.”

At the time, Congress did nothing to rein in the bailouts. It allowed them to continue.

Or consider the rapid expansion of so-called “affordable housing goals” by Government Sponsored Enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac through the 1990s and 2000s that helped fuel the subprime housing bubble that brought the global economy to its knees.

The companies had been given express authorization to act as they did by Congress when it passed the GSE Act of 1992. Here, the abdication had been at the outset.

Or there is also the Environmental Protection Agency’s 2009 carbon endangerment finding that regulated carbon dioxide as a harmful pollutant under the terms of the Clean Air Act even though the original law never contemplated such a regulation.

Congress’ response has been, again, to provide the funds necessary for the agency to continue making up rules. Yet, the original problem was really created when Congress gave the agency such vast powers to regulate when it created it in 1970.

Or then there is the outsourcing of the nation’s monetary policy to the unelected Federal Reserve, as happened 102 years ago in 1913 when the Federal Reserve Act was adopted.

In 2010, under Dodd-Frank, Congress did order an audit of the central bank’s many bailouts during the financial crisis. It even turned up some $442.7 billion of money being created and simply given to foreign banks — quite a smoking gun of crony corruption. But then Congress did nothing with the findings.

Or one might also ponder that more than 86 percent of the federal budget gets spent whether Congress votes to appropriate any monies at all, as occurred in the most recent partial government shutdown of 2013.

Here, again, is an abdication of Congress’ lawmaking and appropriating powers to an automatic, permanent funding of governmental institutions that would go on functioning if Congress was dissolved.

I could go on, but in each instance, Congress has abdicated its constitutional lawmaking powers, either outright or through tacit acceptance of each executive usurpation.

This lack of participation by the people’s representatives — who constitutionally are supposed to be the nation’s lawmaking body — and yet who appear to have little role in actually governing, is as destructive to the liberty of the polity as a whole as anything else.

Congress, like the people, are on the outside, looking in. For, what can one do but merely observe our presidential system, to look upon an executive branch that over generations has progressively been delegated the power to act independently of the other branches. If Congress is ambivalent about exercising its own constitutional power, it will surely continue to lose it.

This dilution of the separation of powers is the very loss of liberty Machiavelli warns against. Consider his description of the later republic that fell to Caesar: “Such contrasting results in the same city arose from nothing other than the fact that the Roman people were still uncorrupt at the time of the [kings], while they were most corrupt in these later times; in the early days, in order to keep the people firm and disposed to rejecting a king it was enough merely to have them swear that they would never consent to another king…”

Later, the people had been so corrupted, Caesar “was able to blind the multitude so that they did not recognize the yoke which they themselves were placing on their necks,” Machiavelli writes. Then, even Caesar’s assassination was not enough to stop what had begun. The latter Brutus who stabbed him ultimately just traded one prince for another. The reign of the emperors was solidified after years of civil war.

So, what to do?

As has been seen in history, the concentration of power seen today in the executive branch is extraordinarily dangerous in republican systems of government. So, what must be done?

The separation of powers, particularly Congress’ power to make law — all of the laws — must be restored. And it must be happen soon. No more broad grants of discretionary authority. No more lawmaking agencies. No more panels of experts. No more automatic budgets. The administrative state must be broken up.

The sort of insulated decision-making taking place was only originally ever envisioned to extend to the President’s Commander-in-Chief war powers upon a Congressional declaration of war. Now it has become an expansive executive, regulatory state with no real role for elected representatives. Sure, sometimes Congress gets a few crumbs, but for the most part, the legislative branch has become a rubber stamp in our presidential, administrative system.

All along this process, the American people have been told sit back, wait for the next presidential cycle. To be patient. There is some truth to this. It probably will take a new presidential administration to fix this. But there are a few caveats.

First, time matters, Machiavelli warns. The situation must not persist for too long, or the whole body politic will be corrupted. Meaning, whichever party wins elections, the Leviathan will continue of its own accord.

Second, not even a single president may be able to fix it: “If a city has begun to decline because of the corruption of its material, and if it ever happens to pull itself up again, this happens because of the ability of a single man living at the time and not because of the ability of the people supporting its good institutions; and as soon as that man is [gone] it returns to its former ways… unless the reformers, before passing on… have managed to bring about her rebirth.”

Meaning, winning an election will not be enough. Whoever the next president is, regardless of political party, he or she has to be dedicated to ensuring that the people’s elected representatives are the ones who make laws and appropriate funds on an annual basis.

This is not a matter of capturing the bureaucracy and governing “smarter.” It is a matter of dissolving the rulemaking bodies.

Barring that, there are few other methods under our constitutional system to restore the separation of powers. There is the Article V convention for proposing amendments by the states, and that is even being attempted now. Many states have already called for the convention. But to succeed, the movement will require leaders at the state level who, unlike Congress, are willing to exercise their constitutionally delegated powers.

If, through their own ambivalence, however, state legislators decide to take a pass on a process for restoring constitutional legislative powers to elected representatives, they will have proven themselves no better than Washington, D.C. It will be just another surrender of liberty.

Whether via the presidential process or a states-ordered convention, whoever leads this effort must have true virtue — an unshakeable love for liberty. Not just a love of individual rights, as we think of in the Bill of Rights and others retained by the people — but the determination to restore true lawmaking power to Congress. There is no greater task facing the nation.

Otherwise, as has been the case in republican systems throughout history that fall into decline, and as Machiavelli warns, “A corrupt people which lives under a prince will never be able to regain its freedom.”

That, from the author of The Prince.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.