“I expect the normalization of monetary policy — that is, interest rates — to begin sometime this year. I expect normalization to proceed gradually, the implication being an environment of rather low rates for quite some time.”

That was Dennis P. Lockhart, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, speaking on Monday, August 24, in Berkeley, Calif. in a speech, saying that the era of zero percent interest rates by the Fed may be coming to an end sooner than anyone thinks.

With markets in increasing turmoil amid China’s credit bubble collapsing and Europe’s continued depression, all eyes are turning to the Fed’s upcoming September meeting. Specifically, everyone wants to know if the Fed will be hiking up its interest rate, which has stood at near-zero percent since the end of 2008.

Given the turmoil, many observers had been predicting that the Fed would be delaying its rate hike, which if it comes would be amid a very slow economy. The U.S. has only been growing at an annualized rate of 1.45 percent this year.

In fact, the U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has not grown faster than 3 percent since 2005. 2006 to 2015 could wind up being the slowest period of economic growth since 1930 to 1939, which clocked in at an average annual 1.33 percent growth rate. Already 2006 to 2014 comes in at an anemic 1.29 percent. These are the worst readings since the GDP was invented as a measure in 1934.

In other words, from a growth perspective, the current economy is as bad, if not worse, than the Great Depression, and comes at the same time as collapsing interest rates, inflation, credit demand, incomes, and slowing of the size of the working-age population.

Because of the slow growth, economists like Lawrence Summers, former Director of the National Economic Council for President Barack Obama, caution against a rate hike. In an op-ed for the New York Times, Summers warns, “Until and unless these new policies are implemented, inflation sharply accelerates or euphoria in markets breaks out, there is no case for the Fed to adjust policy interest rates.”

On the other hand, the Fed has been signaling that policy normalization has been on the horizon for months.

Previously, the nation’s central bank had promised as recently as January 28 that “it can be patient in beginning to normalize the stance of monetary policy.” Meaning, a rate hike was not expected any time soon. But then in its March 18 statement, this line was dropped, yet the Fed still promised that “an increase in the target range for the federal funds rate remains unlikely at the April Federal Open Market Committee meeting.”

By July, the Fed was singing a more upbeat tune, saying, “The Committee anticipates that it will be appropriate to raise the target range for the federal funds rate when it has seen some further improvement in the labor market and is reasonably confident that inflation will move back to its 2 percent objective over the medium term.”

So, despite the ongoing correction in U.S. stock markets and those overseas, it may not be enough to move the Fed off of the trajectory they have been on for months.

In fact, assuming the economy is headed for another downturn, what would be remarkable is if the Fed were to keep interest rates at near-zero levels — leaving it no room to maneuver when unemployment really does begin rising again in earnest.

The problem with the Fed’s short-term policy rate is it will not move unless the Fed deems it so. Markets cannot push it around. And it has been at near-zero percent for nearly seven years. If markets were setting the rate, it might have risen back up years ago. A rate hike, in that context, then might be long overdue.

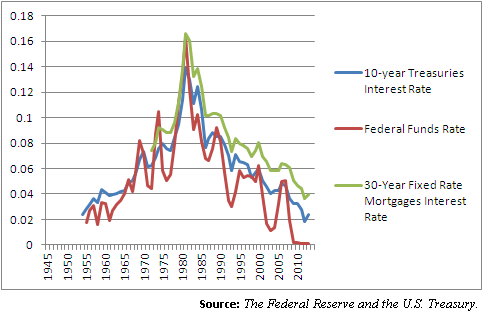

But observers should not overestimate such a hike’s impact. The Fed has hiked rates upward several times over the past 30 years, and yet, each time, interest rates continued along their overall downward trend.

Often those hikes came right before recessions. So a rate hike would probably be a bearish indicator. But it is a symptom, not the cause. Those recessions would have happened anyway.

The fact is, financial markets have been living off easy money for almost a decade since the financial crisis. Should the Fed decide against raising interest rates, then everyone will be complaining that the Fed is out of bullets when the next recession hits.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.