After 7 years of historically low near-zero percent interest rates, the Federal Reserve finally hiked its benchmark interest rate to the new range of 0.25 percent to 0.50 percent on Dec. 16.

Long have economists and other market observers warned that this move by the Fed would lead to higher interest rates for borrowers, homeowners, and others.

And so, naturally, there has been almost no discernible impact on interest rates whatsoever.

10-year treasuries were at almost 2.27 percent on Dec. 15, the day before the Fed’s announcement. On Dec. 28, they were at about 2.24 percent, pretty much the same.

30-year conventional mortgages according to Bankrate.com were at 3.87 percent on Dec. 15, and at 3.91 percent by Dec. 25, virtually unchanged.

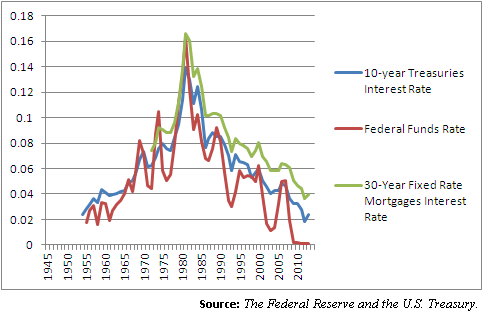

Overall, interest rates have been collapsing long-term for 30 years, after the Great Inflation ended in the 1980s.

Yes, there were times when rates would come off their lows, but the overall downward trajectory has been clear.

One explanation for the lack of movement in the near term is that by moving a mere quarter a percentage point, the Fed has not done anything all that dramatic, and so no notable impact on rates should really be expected.

The other is that by setting the low rate, the Fed actually has no real impact on market interest rates, which are determined by other factors, such as demand for credit.

That was certainly the view of former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, very much downplaying the extent to which the nation’s central bank “controls” interest rates in his inaugural blog post for the Brookings Institution.

“Except in the short run, real interest rates are determined by a wide range of economic factors, including prospects for economic growth — not by the Fed,” Bernanke wrote.

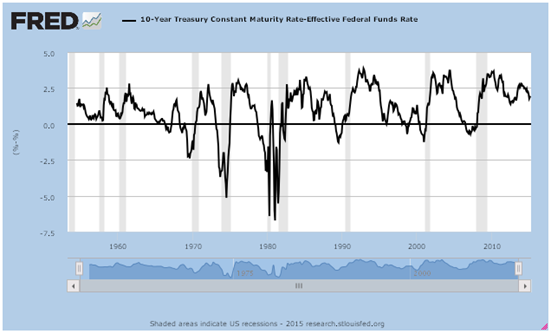

Still, the concern remains that by raising interest rates, the Fed risks an inverted yield curve — where short rates are higher than long rates — which has been historically linked to recessions as credit contracts.

On the other hand, with this particular concern, there is no claim really being made that the Fed’s short rate pushes other longer rates higher. And one thing we know for certain is that rates have inverted several times over the past many decades. That alone might dispel the idea that the Fed plays a highly active role in setting long-term interest rates. Otherwise, the yield curve might not invert at all.

But another thing to keep in mind is that the Fed’s short rate is an artifice, that is, an approximation by policy makers of what the rate should be given current conditions. Whereas other interest rates are determined by market forces, such as financial institutions buying and selling paper at particular price points, and the actions of borrowers to seek credit in the first place.

When the rates have inverted, it may have been after Fed rate hikes, but more recently has occurred as longer rates continued to sink along their 30-year downward trajectory. After all, U.S. treasuries have long been a safe haven asset for pensions but also to grab during downturns.

Which may be the biggest reason of all to believe that rates will continue sink over the longer term.

How low could they go?

Just look to other developed nations, like Japan, where its 10-year government bond yield is down to 0.267 percent. Or Germany, with its 10-year yield down to 0.564 percent.

In the short term, the only thing the higher federal funds rate might mean is smaller profits for financial institutions that rely on borrowing from the Fed as the difference between yields narrows.

And since the Fed does appear to hike rates prior to recessions — although sometimes the downturn takes years to occur — it could be a bearish indicator as the central bank may simply wish to give itself wiggle room with enough lead time for when the next downturn really does come.

Which perhaps after the last cataclysmic downturn, may be the thing everyone should really be worried about, not higher interest rates.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.