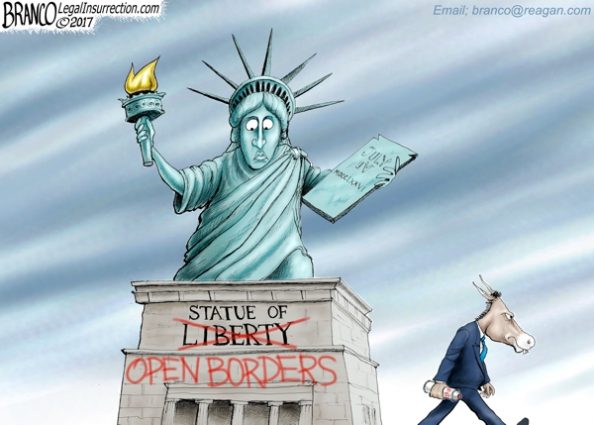

Cartoon c/o Legal Insurrection.

There is no constitutional right to immigrate to the U.S. or to be a refugee, but courts may be about to legislate one from the bench.

It is hard not to worry that such an outcome is imminent as the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals considers briefs from the Trump administration and the states of Washington and Minnesota, who are suing to overturn the temporary travel restrictions issued by President Donald Trump against seven countries that are terrorist hot spots.

For now, the court is considering whether to uphold a temporary restraining order issued by District Judge James Robart against the Trump executive order, which was only supposed to last 90 to 120 days, enjoining the administration from implementing parts of the order pending trial.

Never mind that Congress delegated to the president broad powers to suspend the normal scheme of immigration and refugee inflows into the country under statute, and that otherwise the president also has broad power under Article II in the conduct of foreign relations.

If this case was being decided on its merits, the states of Washington and Minnesota would never have been granted standing to sue on behalf of people living in foreign countries like Iraq, Syria and Iran who do not even have visas.

Yet, here we are, because this case is apparently not being decided on its merits — and it was as plain as day the moment Judge Robart issued his ruling without any legal analysis of the standing question, the most obvious weakness of the case.

And it could get worse. What if the 9th Circuit decides, with the Supreme Court composed 4-4, to quickly make a broad ruling that extends constitutional and legal protections to non-visa holders overseas for the first time in U.S. history?

Given that, and the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals’ liberal bent plus its general tendency to issue atrocious rulings, if the American people are not comfortable with that court determining for itself that everyone is allowed to immigrate to the U.S., say, as a matter 5th Amendment due process, then we might all be better off if President Donald Trump rescinded those parts of his executive order.

Although not desirable in the normal course of governing, particularly when you know you’re right, partially rescinding the order would render current cases against it moot before they ever get to proceed to their merits.

If the executive order’s controversial provisions have been rescinded, then there can be no case against it.

The travel ban was supposed to be temporary anyway. So, while Trump may have been well within his constitutional powers to issue such a ban, it is not worth losing the ability to issue such a ban for all time when conditions truly warrant it to fight an uphill legal battle.

Fighting in court for a 90-day temporary travel restriction against visa holders and a 120-day suspension of refugees for a period longer than those times makes no sense. And there is no guarantee that Judge Neil Gorsuch will have been confirmed by the Senate yet when the 9th Circuit is done. If the Supreme Court were to split 4-4, the nation would be left with whatever standard the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals decided on.

The 9th Circuit knows this, and if the case is decided quickly enough before Gorsuch can be seated, could inevitably confer some sort a constitutional and legal right to immigrate to the United States where none currently exists — a major legal policy goal of the hard left. That would be the worst possible outcome.

That in turn could make implementing changes to the current scheme of immigration impossible not only for future presidents in exigent circumstances, as with the temporary travel restrictions, but also by Congress, which depending on how the 9th Circuit rules, may be barred from facilitating changes to immigration law that attempt to restrict immigration even from terrorist hotspots, particularly if the court makes a broad ruling on the basis of due process.

In other words, the precedent that may come out of pursuing appeals in the 9th Circuit could be broad and terrible from both a constitutional and sovereign perspective, and there may not be time for a fully constituted Supreme Court to undo the long-term damage inflicted.

If President Trump believes that the 9th Circuit is capable of legislating such an outcome, then the only responsible thing to do is to partially rescind the executive order. It may not be what the president wants to hear right now, but the writing on the wall is becoming clear.

Americans for Limited Government President Rick Manning blasted the development in a statement, “Our nation either has borders or it does not. The President of the U.S. is clearly authorized under the law to take actions to secure those borders against those persons who he believes may cause a threat to national security. The seven-nation pause on travel ordered by Trump to allow additional vetting of refugees and other immigrants is a basic assertion of our sovereign rights as a nation.”

Manning continued, “If the courts determine that this basic national security protection does not exist, then we might as well defund the INS and ICE, eliminate all visas and just let whoever wants to come show up at our doors. The absurdity of this case is that it turns prudent immigration policy on its head, destroying our nation’s most basic right to defend its borders.”

Again, Washington and Minnesota should have no case to bring because of a lack of standing, but here we are.

The stated purpose of the executive order was in lieu of a more permanent vetting regime being implemented. A federal case against prospective rules for vetting that have not been issued yet would be impossible to sustain, even at the 9th Circuit. That is why Robart did not enjoin implementation of the promulgation of the vetting system that the order calls for.

The easiest way past this is to drop the temporary travel restrictions. Trump doesn’t need them to get to his vetting process, and the courts may not allow them to be utilized in the 90 to 120 day windows the president established.

Theoretically, it is possible the court might ultimately separate the two issues of the suspension of new visas from immigrants who have already been issued visas, or even rule in Trump’s favor. However it is notable that Judge Robart did not do so at the outset, essentially compelling the U.S. to continue issuing new visas against the administration’s wishes. Nor has the 9th Circuit granted a stay of Robart’s decision.

Therefore, fighting this particular executive order out in court is not at all worth the risk. If the administration eventually prevails, it will get to implement a temporary travel restriction one day, probably not even this time since the practice is currently enjoined under the order. If the plaintiffs win, the 9th Circuit might issue a ruling creating precedent that obligates the U.S. to take in all-comers for all-time.

Almost nothing will be gained, and it is very possible the administration will lose the ability to later issue its new vetting policies before it ever gets to issue them. Why? The courts may create precedent that makes additional vetting yet another supposed due process violation.

On the merits, Trump was well within his rights to issue the restrictions both legally and constitutionally, and it is not his fault for acting to protect the nation, but this case is not being determined on its merits. Judge Robart issued his ruling without any legal analysis whatsoever, tipping his hand that the plaintiffs are likely to prevail in the end.

Nobody should want to find out what sort of decision is going to be made by the time the 9th Circuit gets its hands on this, potentially conferring constitutional rights on non-citizens to immigrate to the U.S. Partially rescinding the executive order and regrouping on implementing the vetting policy, either legislatively or as stipulated by the order, may be a wiser approach.

In the meantime, Congress could also examine the issue by affirming the president’s power to issue such restrictions in a wider scheme addressing immigration and refugees from the Muslim world, but in a more focused manner. That said, Congress had already registered its sense in 1952 when it delegated the power to issue such restrictions to the president.

Trump could also turn this issue into a political one rather than a legal one by asking members to vote on admitting immigrants and refugees from terrorist hot spots using the bully pulpit. Who wants to vote against sensible vetting policies? In the process, Trump could create a political consensus for his policy, which in principle should stand a better chance in court.

Trump is under no obligation to accept the battlefield he has found himself on in the 9th Circuit. The process federal courts are currently undertaking against Trump’s travel restrictions may be rigged, and Trump does not have wait around to see what happens next.

Trump can change the current stalemate by simply rendering these cases moot and partially rescinding the executive order, taking away the judicial attempt to legislate from the bench. By now, the president must anticipate that he may not prevail on the issue of temporary travel restrictions. By pursuing the appeal at this stage, then, the administration could also be risking its longer-term intended policy on vetting, particularly if the 9th Circuit produces a broader ruling contrary to U.S. security interests that sets up an impossible precedent to overcome.

In the long run, the nation’s security is going to need that additional vetting, which is more important than any temporary travel restrictions. Sadly, it might be better for the president to live to fight another day on this issue by partially rescinding the executive order at least until such time the Supreme Court is ready to hear such a case.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.