There was good news on the economic front as the Bureau of Economic Analysis revised upwards reported growth of the Gross Domestic Product in the second quarter from an inflation-adjusted 2.6 percent annualized to 3 percent annualized.

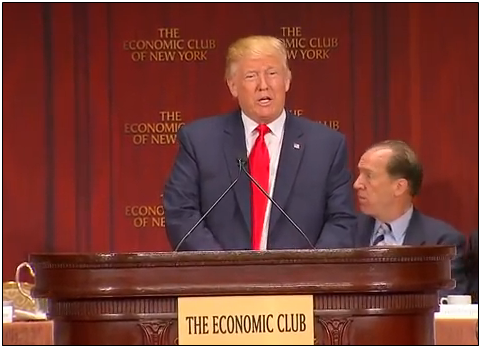

The news was heralded as great news for the American people by conservative media outlets and the Trump administration, naturally so, but a word of caution. 3 percent growth for a single quarter does not mean 3 percent growth for the entire year.

Growth in the first quarter remained at 1.2 percent, meaning, the growth rate for the year so far averages out to only about 2.1 percent.

To get to 3 percent for the year, the economy will still have to grow at about an annualized 3.9 percent for the remaining two quarters each just to get to the average of 3 percent for the year. Not saying it cannot be done but whether it will be done remains to be seen.

Although it is true that growth never rose above 3 percent annually during the Obama administration, there were many quarters where it grew above that level on an annualized basis. For example, in 2014, in the second quarter, the economy grew at an annualized 4.6 percent, and in the third quarter it grew at an annualized 5.2 percent. But because in the first quarter it shrank at an annualized 0.9 percent and only grew at an annualized 2 percent in the fourth quarter, the average growth for the year was still less than 3 percent.

Meaning, we’re not yet out of the slow growth doldrums that have plagued the U.S. economy for more than a decade — where the economy has not grown above an inflation-adjusted 3 percent annually since 2005 and not above 4 percent since 2000. From a growth perspective, the economy the past decade prior to President Donald Trump taking office was the worst on record.

The Trump administration should be mindful of the challenges the U.S. economy still faces — and manage expectations accordingly. The slowdown has been several years in the making, and it will not be turned around by sheer will or optimism alone.

Fortunately, it appears the President has surrounded himself with sober economic advisors, including Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney. The budget submitted by OMB does not project 3 percent growth annually until 2021. And in a comprehensive oped for the Wall Street Journal on July 12, “Introducing Maga-nomics,” Mulvaney outlined the several conditions for getting there, including “Tax reform… Curbing unnecessary regulation… Welfare reform… Smart energy strategy… Rebuilding America’s infrastructure… Fair trade for America… Government spending restraint… [and] the size of the workforce.”

Three of those, curbing regulations, trade relations and smart energy strategies are all in the White House’s court. Although reducing the trade deficit will be difficult. It’s actually larger on average per month in 2017 at $46.1 billion a month than it was at this point in 2016 at $41.6 billion. That, even as U.S. exports have increased. The trouble is that imports grew even faster. Also, currency mismatches overseas remain a challenge.

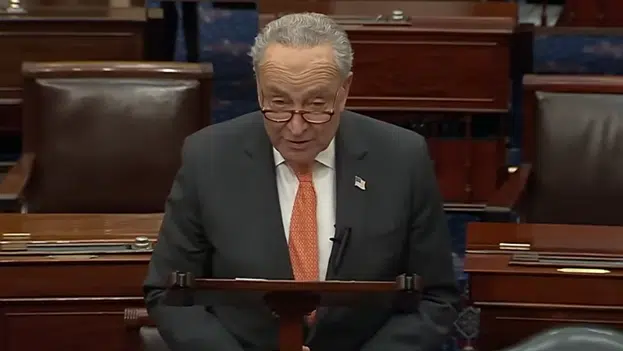

But other essential items, including tax and welfare reform and spending restraint, depend on Congress and it remains unclear whether the GOP leadership there can create the consensus to get big things done.

Another factor cited by Mulvaney, the size and growth of the workforce, is dependent on other demographic factors — such as population growth of the working age population.

It also depends on social conditions — for example young people receiving the right kind of education and job training to obtain the jobs available — that may be beyond the scope of the government’s ability to affect in the near-term or even over the course of four years.

On those latter counts, the slower growth rate of the working age civilian labor force has correlated with the economic slowdown seen since 2000. The more people who enter the labor force, the more momentum the economy tends to have and vice versa.

As far as education and job training goes, there 131 million Americans over the age of 25 with some college or with degrees competing for only 55 million jobs that require that sort of education. That leaves the other 76 million or so people overeducated and yet unqualified for the many other jobs that actually require some form of vocational training. This is a generational challenge, and will not be fixed overnight.

This might help explain the slowdown of labor force growth in part but other factors including automation and outsourcing also loom.

In short, getting the growth engine of the U.S. economy moving again is not going to be so easy — and the economic advisors in the White House need to manage the President’s as well as the public’s expectations in this regard. It is good we have a president who is optimistic. Trump’s goal of 3 or 4 percent growth is laudable.

But to get to where we need to be will require outlining the real challenges facing the economy, even if it includes unpleasant news, and seek to aggressively address them via pro-growth policies.

Happy talk alone won’t make the economy grow robustly. Just ask former Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.