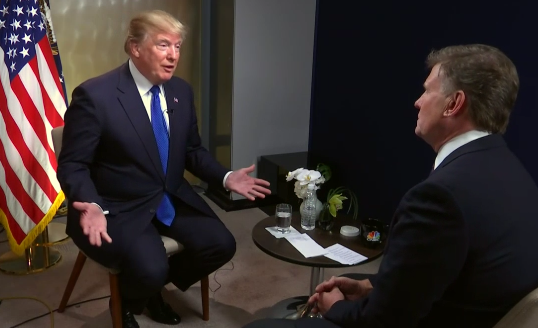

“I want reciprocal. If they’re going to charge us 100 percent for a motorcycle, it should be 100 percent the other way, too.”

That was President Donald Trump in an interview with CNBC’s Joe Kernen on Jan. 26 while he was on the ground in Davos, Switzerland renewing his call for “fair and reciprocal” trade.

Here, the President was referring to India’s 100 percent tariff on motorcycles manufactured in the U.S., including Harley-Davidson, and telling the subcontinent that if it’s going to put that kind of tax on U.S. goods, then it should go in the other direction, too.

Trump is right. Sometimes the only incentive for another country to lower their tariff wall is for them to feel tariffs, too. That is how tariffs have been lowered the past century following Smoot-Hawley — reciprocally. When each side is mutually agreeing to lower their tariffs in an enforceable, the world gets closer to free trade.

In the case of India, a good place to start is the $4.7 billion of trade preferences the U.S. gives under the General System of Preferences.

At $19 billion a year, the General System of Preferences, which expired Dec. 31, “provide opportunities for many of the world’s poorest countries to use trade to grow their economies…” according to the U.S. Trade Representative website.

Right on its face, the program is not designed to serve U.S. interests at all but to redistribute wealth globally. It goes to “undeveloped” nations, even to large economies in the world. India, which also charges 13.4 percent most favored nation tariffs on U.S. goods, is the sixth largest economy in the world and is actually the top recipient of this program. Trump should pull India out of it and instead pursue a bilateral trade relationship.

Elsewhere, Trump promoted his “fair and reciprocal” trade agenda at the World Economic Forum at Davos. In his speech, he said, “the United States is prepared to negotiate mutually beneficial, bilateral trade agreements with all countries. This will include the countries in [the Trans-Pacific Partnership], which are very important. We have agreements with several of them already. We would consider negotiating with the rest, either individually, or perhaps as a group, if it is in the interests of all.”

This is exactly right. Particularly, pursuing bilateral agreements is a far better approach than the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which would have included 12 countries including the U.S. One size fits all hasn’t worked at the World Trade Organization, and it was not going to work in the TPP.

Since taking office, significant progress has already been made by President Trump in putting America first on international trade and other globalization issues. The U.S. left the Trans-Pacific Partnership, is renegotiating NAFTA, left the Paris Climate Accord and has ramped up vigorous trade enforcement, starting with actions against sugar dumping by Mexico and then washing machine dumping by South Korean companies Samsung and LG.

Looking forward, the U.S. still offers significant trade preferences to countries without getting much in return. The General System of Preferences is just one example of all the steps that need to be taken to get to “fair and reciprocal” trade.

China, the second largest economy in the world, is still given “special and differential treatment” as a “developing” nation at the WTO, and in the meantime, world trade rules do not address currency manipulation including China’s fixed exchange rate and the hording of U.S. treasuries.

Above all campaign promises, President Trump’s call to renegotiate NAFTA is the reason he won in Nov. 2016. It’s a bad deal that puts Mexico on equal footing with the U.S. and set the stage for the WTO and even worse trade deals. The President must get a better deal on NAFTA or leave it.

The consequences of these unbalanced trade agreement are clear. U.S. market share of manufacturing exports worldwide peaked in 2000 at 13.98 percent, and has been declining ever since, according to the World Bank. In 2016, it was down to 7.91 percent.

At the same time, labor participation among 16-64-year-olds has been dropping, resulting in some 9 million Americans being displaced from the labor force had participation remained the same.

As a direct result of fewer Americans entering the labor force, U.S. economic growth has slowed, not growing above 4 percent since 2000, and not above 3 percent since 2005.

To get back to robust growth and to create new job opportunities for displaced workers, the U.S. needs to boost exports with better trade deals. But to get there, other countries may need to feel what reciprocity is like first before they will come to the table. It is time for President Trump to take off the gloves on trade.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.