Nike made major headlines and drew sharp criticism when it decided to nix a “Betsy Ross” flag design on a sneaker — 13 alternating red and white stripes with a field of blue in the upper left with 13 five-pointed white stars appearing in a circle — because it was thought of as a symbol of white supremacy by former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick.

So the popular myth goes, in 1776, Betsy Ross single-handedly designed the first American flag with George Washington, who personally approved of it and took it into battle with him.

Since slavery was still allowed at the time, the social justice warriors (hereafter “SJWs”) at Nike reasoned, it symbolizes a time of oppression.

There’s only one problem. The “Betsy Ross” flag was not really popularized as being the original flag until 1876 for the 100-year celebration of independence — after slavery had been abolished in 1865 after the bloody Civil War. This is perhaps owed to Ross’ grandson in 1870, William J. Canby, presented a paper to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania that forms the basis of the claim based on a family oral tradition that he only learned of in 1857, which lent itself to the popular legend. When Harper’s New Monthly Magazine picked up the account in 1873, it reached a large audience for the first time. Come 1876, it was common to see the “Betsy Ross” flag.

But that is likely a coincidence. The Canby account does not mention the circular star pattern (or any pattern for the stars) at all. According to antique flag collector Jeff Bridgman, “Circular star patterns were a favorite in the period between the Civil War (1861-65) and the 100-year anniversary of our nation’s independence in 1876.”

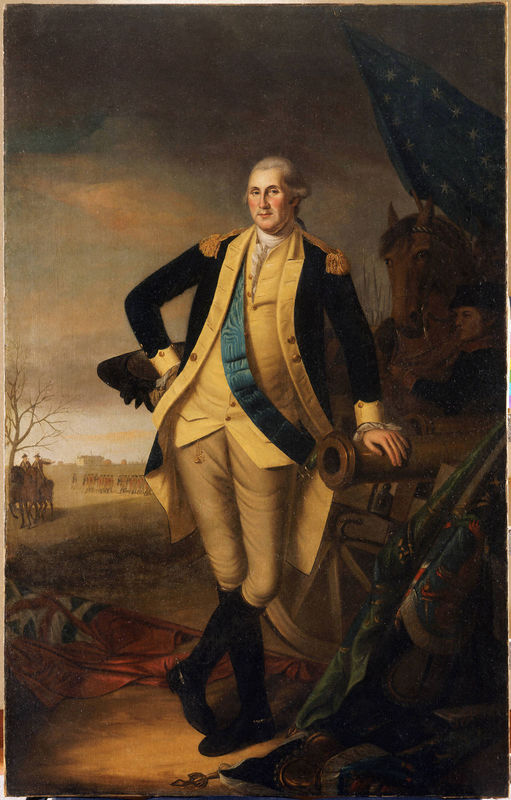

In fact, the Flag Act of 1777 did not specify a layout for the official Stars and Stripes, and throughout the war various customized flags were in use depending on the militia or regiment. Although versions of such a circular display of stars design were in use during the Revolution, such as Washington’s Commander-in-Chief flag depicted in a 1779 portrait by Charles Willson Peale, those included six-pointed stars on a field of blue and no stripes.

The earliest reference may have been a 1792 painting after the war by John Trumbull, although the number of points on the star is not clear (Ross’ innovation was said to be switching to the five-pointed star) and looking closely there only appear to be 11 stars (probably owing to the relatively tiny space on the canvas dedicated to the flag), but may have simply been an innovation of the flag shown in Peale’s portrait.

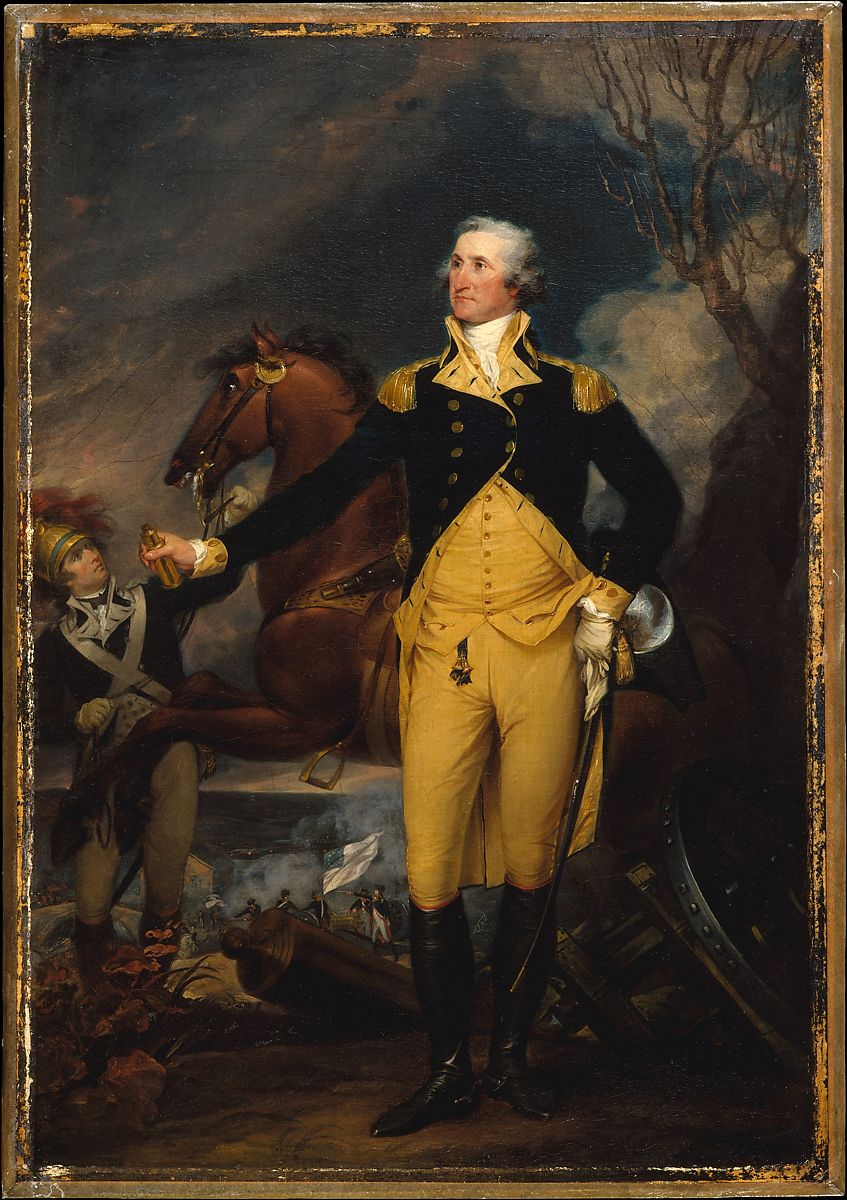

Later paintings, such as “Washington Crossing the Delaware” by Emmanuel Leutze in 1851, clearly shows the classic “Betsy Ross” design with the five-pointed stars, indicating some usage prior to Canby’s paper but still long after the Revolution. However, the popularity of the painting may have helped lend itself to the popularity of the design itself during the post-Civil War era.

As for when the circular star design itself became attributed to Betsy Ross, that might not have been until even later, in 1892, according Bridgman’s “New Constellation” exhibit at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia. Bridgman writes, “The first time that a star configuration gets attached to the Canby story apperas to have occurred during the last decade of the 19th century. In 1892, Charles Weisgerber painted a nine-by-twelve-foot rendition of the fabled meeting between Betsy and George Washington, in which there is a flag with a circular wreath. In 1898, Weisgerber and a ‘group of concerned citizens’ sought to preserve Betsy’s former Philadelphia residence at 239 Arch Street, where she lived at the time the flag would theoretically have been sewed. Weisgeber moved his family into the house and immediately opened to the public the room in which Betsy was said to have worked her magic. Ten-cent memberships were sold to fund renovations and donors received a small calendar, to which a cotton 13-star Betsy Ross pattern parade flag was affixed.”

Adding to the legend, per Bridgman, “In that same year, Rachel Abright, Betsy’s granddaughter, began making little hand-sewn flags in the east wing of Independence Hall and selling them to tourists, while at the same time disseminating family folklore. Sometime around 1902, Abright’s daughter, Saraha M. Wilson, joined her mother in this venture, producing her own flags. She may have, in fact, been assisting all along, inscribing signatures and dates on the hoist buildings of the flags for her mother, who could certainly sew with expert precision, yet may have been unable to write legibly. Albright and Wilson proudly proclaimed that a circular wreath pattern was the design of the very first flag, in 1777, but no hard evidence exists to substantiate it.”

The “Betsy Ross” design was never officially adopted by the U.S. government. The first flag adopted was designed likely by Francis Hopkinson, a member of the Continental Congress who also signed the Declaration of Independence. Hopkinson is credited with helping to design the Great Seal and U.S. currency. In 1780, Hopkinson had requested payment from the Board of Admiralty for his design of the “flag of the United States of America” in exchange for some wine. However, Congress refused him, on the grounds that others had helped contribute to the design. From 1777 to 1795, the flag appears to have had stars that were staggered, not in a circle, although many designs were used. The fact is, no official configuration of the flag existed until 1912, when President William Howard Taft issued Executive Order 1556.

As for the historical Betsy Ross, some of the historical documentation does confirm she was a flag-maker. For example, she made flags for the Pennsylvania State Navy Board for ship’s colors based on receipts from that time. Whether she designed the circle stars design personally with the aid of George Washington, however, though relies solely on her grandson’s account almost a century later.

Meaning, the SJWs at Nike canceled a product based on a legendary recounting of history that may not even be accurate and is most certainly misplaced. When the “Betsy Ross” flag reached the height of its popularity was in a post-Reconstruction America where slavery had already been abolished.

This revisionism is disgraceful.

The official Stars and Stripes, regardless of one’s views about slavery, was most certainly the flag that was flown by the Union in the Civil War. It was the same flag that William Carney, the first black recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor, rescued on July 18, 1863, at Fort Wagner in South Carolina. Carney had noticed the man carrying the flag was wounded, and he carried it in his stead and upon returning it to his regiment, reportedly stated, “Boys, the old flag never touched the ground.” Carney fought with the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the state’s first all-black regiment.

Nobody should be ashamed to fly the Stars and Stripes this July 4, whether it’s the “Betsy Ross” design or otherwise. That is the flag men and women have fought and died for the cause of liberty since the founding of the republic.

In any event, the flag for the purposes of July 4 is about the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776 that adopted the eternal proclamation that “all men are created equal” that would form the basis of Abraham Lincoln’s denunciation of slavery in the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858. Meaning without the Declaration, without the American Revolution, and Lincoln is never inspired to take up the cause of abolition, he never rises to fame nationally, and is not elected President in 1860.

Here is what Lincoln said about the American flag on Feb. 16, 1861 on the eve of the Civil War at Dunkirk, New York: “I stand by the flag of the Union, and all I ask of you is that you stand by me as long as I stand by it.”

Abraham Lincoln never gave up in the Civil War nor on the question of abolition and certainly not on the Union and the flag that it represented. Why have Nike and Colin Kaepernick?

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.