Financial media were quick to report a slowdown in manufacturing, that found the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) dropping below 50 and to its lowest level since Jan. 2016. Anything below 50 indicates a contraction.

Looking for the culprit in the slowdown? Some publications attributed the slowdown in manufacturing to tariffs, but they should look no further than the strong dollar.

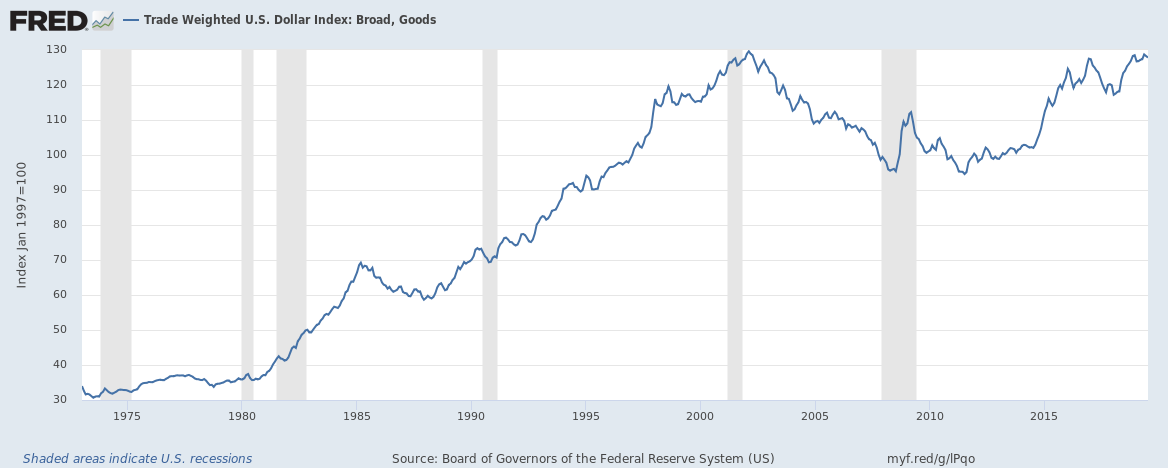

Especially, when one considers the relative strength of the U.S. dollar versus other currencies, the slowdown is unsurprising. The trade-weighted U.S. Dollar Index on broad goods is up at about its highest levels on record going back to 1973 at about 130. This makes U.S. exports to other countries more expensive, and imports to the U.S. from overseas cheaper.

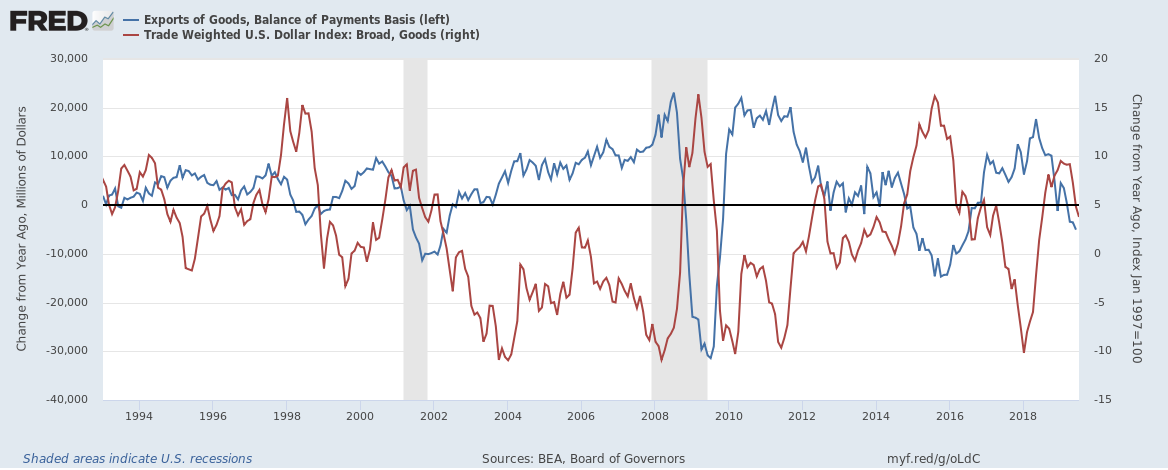

The strong dollar has historically been linked to declines in U.S. goods exports, including manufacturing, an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau and Federal Reserve data shows, predating the tenure of President Donald Trump and his tariffs. This vindicates contentions by Trump, who has been hammering the Fed for months over what he says is the dollar being too strong relative to foreign currencies including the Chinese yuan and the euro.

Turns out, Trump is right. In periods when the dollar was weakening, U.S. exports tended to accelerate, and in periods where it strengthened, exports slowed down or even contracted. Which, by the way, is precisely what the economic literature on the topic of exchange rates predicts would happen.

Trump tweeted on Aug. 22, complaining about the strong dollar, “Germany sells 30 year bonds offering negative yields. Germany competes with the USA. Our Federal Reserve does not allow us to do what we must do. They put us at a disadvantage against our competition. Strong Dollar, No Inflation! They move like quicksand. Fight or go home!”

Since at least Oct. 2018, Trump has been calling for lower interest rates by the Fed. The federal funds rate at 2 percent to 2.25 percent, as low as that seems, is still well above the 10-year treasury and the two have been inverted since May. Although the Fed seems to agree that its policy rate is too high at its July meeting, its cut of 0.25 percent was not adequate to cure the inversion.

So, there appears to be broad agreement that rates are too high and in absolute terms, the dollar is as strong as it has ever been. Trump has been making the case for months, perhaps mindful of historical data showing that when U.S. monetary policy is too strong relative to other currencies, it is often followed by slowdowns or in extreme cases, recessions.

That is important because the dollar’s impact on exports appears to be policy neutral. That is to say, the relationship between strengthening dollars and slowing U.S. exports existed prior to Trump, and prior to his current trade standoff with China, which stands at 25 percent on $250 billion of Chinese goods, and saw an escalation up to 15 percent on the remaining $300 billion of goods over the weekend.

Meaning, the strong dollar would have been a problem for manufacturing and exports overall, including agriculture, even if Hillary Clinton were the president today.

Clearly, President Trump’s frustration is justified, but will the Fed chip in and slash the federal funds rate this month when it meets and cure its own inversion with U.S. treasuries?

Trump’s argument with the central bank comes as Former New York Federal Reserve President Bill Dudley wrote an oped on Bloomberg saying that “the election itself falls within the Fed’s purview,” and that “Trump’s reelection arguably presents a threat to the U.S. and global economy, to the Fed’s independence and its ability to achieve its employment and inflation objectives.”

Dudley added, “If the goal of monetary policy is to achieve the best long-term economic outcome, then Fed officials should consider how their decisions will affect the political outcome in 2020.”

Considering the strength of the dollar, something the Fed can impact via interest rate policy and open market operations to buy bonds, it’s hard not to reach the conclusion that acting politically is what the Fed already does. The last time the dollar spiked was in the winter of 2016, right after the Fed had hiked the federal funds rate for the first time since the Great Recession. The central bank then immediately paused on any further rate hikes until after the 2016 election, and then began hiking in earnest after Trump won.

But Trump is not powerless. He ought to work with U.S. allies and trading partners to discuss exchange rate policy and attempt to craft an international monetary accord

In addition, the U.S. Treasury operates the Exchange Stabilization Fund, with which it operates to “purchase or sell foreign currencies, to hold U.S. foreign exchange and Special Drawing Rights (SDR) assets, and to provide financing to foreign governments. All operations of the ESF require the explicit authorization of the Secretary of the Treasury (‘the Secretary’),” according to Treasury’s website. Meaning, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin could act to dump dollars on foreign exchange markets to bring the price down a bit.

Matt Phillips of the New York Times on Aug. 6 pointed to the Exchange Stabilization Fund at the U.S. Treasury as something that could be used: “The People’s Bank of China has the ability to print renminbi to weaken the currency if the exchange rate gets too high. On the flip side, Beijing has $3 trillion in reserves it can deploy to keep the currency from getting too weak. Right now, the United States doesn’t operate that way. It has some capacity to intervene in financial markets by using the Exchange Stabilization Fund, a vehicle under the control of the Treasury secretary, with about $100 billion of buying power.”

The latest balance sheet shows $93 billion in the Exchange Stabilization Fund, but it could get larger — with the help of the Fed. According to an Aug. 21 report from the Congressional Research Service, “In addition to its initial capitalization ($2 billion), Congress allowed the ESF to remain outside of annual appropriations. Instead, the ESF retains all of the earnings from its operations. The main limitation on the ESF’s ability to intervene to reduce the value of the dollar is the amount of dollar-denominated assets in its portfolio, which are $22.48 billion as of March 2019. In order to secure more dollars for foreign exchange operations, Treasury could (1) seek an additional appropriation from Congress;(2) monetize its holdings of IMF special drawing rights (SDR, an international reserve asset), valued at $50 billion, by temporarily selling them to the Fed; or (3) engage in a currency swap arrangement called ‘warehousing,’ in which the ESF sells foreign currency to the Fed and agrees to repurchase it at a later date, during which the Fed credits dollar reserves to the ESF for the duration of the swap.”

In addition, the Fed has all the same powers as the Exchange Stabilization Fund, but without limits. Per the Congressional Research Service, “The Fed can also purchase foreign currencies to reduce the value of the dollar; but unlike the Treasury, it is not limited in how much it can purchase. Because the Fed controls the money supply, it has the option to create bank reserves as desired to purchase foreign currencies.” Meaning, the Fed, absent any action by the Treasury, could absolutely move to devalue the dollar from its current position.

The Fed cutting interest rates would also help, per the Congressional Research Service: “In addition to foreign exchange intervention, economic theory predicts that short-term interest rates, the Fed’s main policy tool, also affect the value of the dollar. The value of the dollar is determined by the relative demand for U.S. goods and services and U.S. assets. In practice, capital flows dwarf trade flows, so the value of the dollar is particularly sensitive to interest rates in the United States relative to the rest of the world. Foreign capital can only flow into the country on net (i.e., when foreign purchases of U.S. securities or physical capital exceed U.S. purchases of foreign securities or capital) through the exchange of foreign currency for dollars. Theory predicts that if the Fed lowers interest rates relative to the rest of the world, it would reduce the demand for U.S. capital, thereby reducing the value of the dollar. This is one of the standard channels through which lower interest rates stimulate the economy. Although U.S. interest rates are currently low, they are even lower for many major trading partners.”

But assuming the Fed is asleep at the wheel, Congress could also move to increase the size of the Treasury Exchange Stabilization Fund or the President may be able to reprogram some limited funds to be deposited into it under an emergency declaration. In either event, the President should direct Treasury Secretary Mnuchin to work with the Federal Reserve Board of Governors to engineer a devaluation, boosting the Exchange Stabilization Fund by buying foreign exchanges and then selling them directly to the Fed.

In fact, the Fed has already authorized this practice, known as warehousing, to occur, in its Jan. 2017 meeting: “the Committee authorizes the Selected Bank, with the prior approval of the Subcommittee and at the request of the United States Treasury, to conduct swap transactions with the United States Exchange Stabilization Fund established by section 10 of the Gold Reserve Act of 1934 under agreements in which the Selected Bank purchases foreign currencies from the Exchange Stabilization Fund and the Exchange Stabilization Fund repurchases the foreign currencies from the Selected Bank at a later date…”

Time is a major factor. If the dollar index shows anything it is that it is very much subject to volatility, and its current strength is a direct result of competitive devaluations overseas. Meaning, price stability, particularly of exports, is impacted greatly by exchange rates, and yet the Fed fails to consider exchange rates in the conduct of monetary policy. Why? Arrangements are already in place to prevent this from happening.

President Trump has watched the manufacturing index fall, and knows that it is the strong dollar that drives it. Now, when you hear or read about his latest complaint about the Federal Reserve, you will understand that it is their strong dollar policy which is blocking President’s Trump’s drive to restore America’s manufacturing base by boosting exports.

Our nation is in an economic war, it is time for the Federal Reserve to join the fight.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.