As long as central banks, financial institutions and pensions continue buying, then there is no sovereign debt crisis and no reason for interest rates to skyrocket.

The U.S. Federal Reserve and the Social Security and Medicare trust funds own a collective $11 trillion of U.S. treasuries, comprising 39 percent of the total $27.97 trillion national debt, and rising, U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve data show.

That figure has increased $2.6 trillion in the past year alone, mostly as the Federal Reserve engaged in massive quantitative easing, purchasing $2.4 trillion of U.S. treasuries in response to the Covid pandemic recession.

Now, as a result, the Fed currently holds $4.89 trillion of treasuries. The Social Security and Medicare trust funds increased about $200 billion the past year and hold about $6.1 trillion of treasuries overall.

Overseas, the debt held by foreigners including central banks has remained stable the past year at $4.2 trillion. That’s about 15 percent of the debt.

Here, the Fed is largely quarantining the gargantuan new federal spending that began in 2020 in order to keep U.S. interest rates low, which has largely worked. 10-year treasuries go for about 1.7 percent, up from 1 percent at the beginning of the year, but about where it was pre-Covid.

But watch for that number to likely begin dropping again as new debt enters the market thanks to the next spending splurge from Congress, its latest $1.9 trillion Covid spending bill.

Despite all of the extra debt being created, there remains massive demand for U.S. treasuries, albeit artificial demand largely being created by the Fed.

And to the extent the central bank continues monetizing — it is currently buying $80 billion of treasuries a month, plus another $40 billion of mortgage-backed securities — expect to see rates to come down again.

In the meantime, expect further drops in the velocity of money.

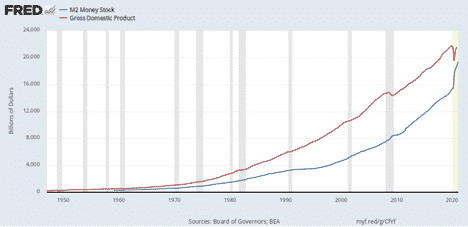

Despite massive government spending, and quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve, the velocity of money, that is, in the ratio of the Gross Domestic Product to the nation’s money supply, has collapsing been year over year since 2000, Federal Reserve data shows.

Investopedia defines the velocity of money as, “The velocity of money is a measurement of the rate at which money is exchanged in an economy. It is the number of times that money moves from one entity to another. It also refers to how much a unit of currency is used in a given period of time. Simply put, it’s the rate at which consumers and businesses in an economy collectively spend money.”

Meaning, we’re printing a lot of money right now and with a huge chunk of it being direct payments like stimulus checks and child tax credits, more and more of it is entering the real economy and yet it’s not doing much to stimulate additional purchases. The money supply is growing faster than the economy.

Shouldn’t that lead to inflation? The past three months, inflation has been running a little hot at an average of 0.3 percent from December to February, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Annualized that would be 3.6 percent inflation, well above the Fed’s traditional 2 percent target. So far, though, the increases are largely concentrated on food and energy, which tend to be volatile.

And yet, inflation too has been pretty much stable, growing at an unadjusted 1.7 percent the past twelve months. How? For the big increases in prices we are seeing now, that is offset by the massive price collapses last year when the price of oil went below zero.

As much of the money being created right now, even more of it is being held back out of the economy as the Fed quarantines the national debt. It’s a cycle that’s been running for two decades. It also points to an overall deflationary environment seen, particularly in the financial crisis and Great Recession, and more recently, the Covid recession.

Which, is little wonder. In the Great Recession, more than 8 million jobs were lost, a dramatic drop in economic activity. The Covid recession was even worse, with 25 million jobs lost when labor markets bottomed last April. Now, more than 16 million jobs have been recovered, and 8.5 million remain to be recovered. That’s a tremendous gap in output that Congress and the Fed are desperately attempting to offset at the moment.

Some ask how long this dance can go on, such unbridled spending and printing money to pay it. And it’s a great question. And the answer is generally as long as there remains surplus demand for U.S. treasuries. As long as central banks, financial institutions and pensions continue buying, then there is no sovereign debt crisis and no reason for interest rates to skyrocket.

But all of that could change at the drop of a hat. Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.