Russia has annexed the separatist cities of Donetsk and Luhansk in eastern Ukraine after Russian President Vladimir Putin recognized their independence on Feb. 21, moving in troops as the U.S. and the West have renewed sanctions against Moscow, including Germany halting the approval process of the Nordstream 2 natural gas pipeline and the U.S. blocking Western purchases of Russian government debt.

The cities, located in the Donbas region, have been controlled by pro-Russian separatists since 2014, and were among the breakaway provinces including Crimea that voted via referenda to secede from Ukraine after former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was removed from power in early 2014, touching off the civil war there. President Joe Biden wrote in his book about pushing Yanukovych out of power in order to get a European Union trade agreement with Ukraine ratified when he was Vice President.

In response, in 2014, Russia annexed Crimea, securing the Sevastopol Naval Base there, but the final fate of the other breakaway regions were, until recently, the subject of the Minsk accords, four-way talks between Ukraine, Russia, Germany and France. Those talks led Ukraine to grant limited autonomy to Donetsk and Luhansk in 2015.

Then, on July 12, 2021, Putin directly challenged the Minsk framework in an essay that called for Kiev to negotiate directly with Donetsk and Luhansk — which predominantly speak Russian — and for the breakaway provinces to essentially determine for themselves if they wanted to secede from Ukraine. Clearly, Putin was saying he believes regions, like Donetsk and Luhansk, where Russian is the number one language should be allowed to be a part of Russia. Similarly, in 2019, Russia granted citizenship to residents of the cities.

“[T]rue sovereignty of Ukraine is possible only in partnership with Russia… [W]e are one people,” Putin declared in the speech, citing “the blood ties that unite millions of our families” and predicting the statement would “be perceived by some people with hostility…” It certainly was. The pro-Ukraine Atlantic Council published a paper days later entitled, “Putin’s new Ukraine essay reveals imperial ambitions.”

Here, in hindsight, the speech pointed to the potential of Moscow recognizing the breakaway republics, which ultimately came true last week on the eve of the invasion, and came a few months after Ukraine imposed sanctions on its pro-Russian opposition party, seizing three news channels. Putin alluded to the alleged move against Russians living in Ukraine in his speech casting himself as their protector, stating, “They are intimidated, driven underground.” He’s got a chip on his shoulder.

In a Feb. 22 televised speech justifying Russia’s actions in Ukraine, Putin questioned Ukrainian statehood altogether, stating, “Ukraine actually never had stable traditions of real statehood,” and then noted the various ways Ukraine’s mere existence threatened Russia, whether as a potential NATO ally or with nuclear weapons, or both.

Putin also demanded a halt to any further NATO expansion and that NATO return to its 1997 borders, citing the threat of intermediate range nuclear weapons, once governed by the now-abandoned 1987 INF Treaty, being able to hit Russia. It’s a long list of demands, all of which have been said to be non-starters by the U.S. and NATO.

But what has really changed?

The pro-Russian breakaway provinces are still pro-Russian breakaway provinces that have been in control of their regions since 2014. In the context of the civil war and the Minsk-led peace talks, the question was what to do with them. Now, even after Russia has put troops into those regions, the question will undoubtedly still be the subject of future diplomatic talks, assuming they even take place.

On Feb. 22, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky floated the idea of cutting off diplomatic relations with Moscow, stating, “I’ve received a request from the foreign ministry. I will consider the issue of severing diplomatic relations between Ukraine and the Russian Federation.”

In a similar vein, the U.S. has cancelled plans for a Biden-Putin summit to discuss Ukraine and likely nuclear security concerns.

Critically, Putin complained that “proposals for an equal dialogue on fundamental issues have actually remained unanswered by the United States and NATO” and that “[t]hese principled proposals of ours have been ignored.”

In other words, both sides are saying diplomacy has failed to resolve the conflict. Sometimes, wars start when dialogue ends.

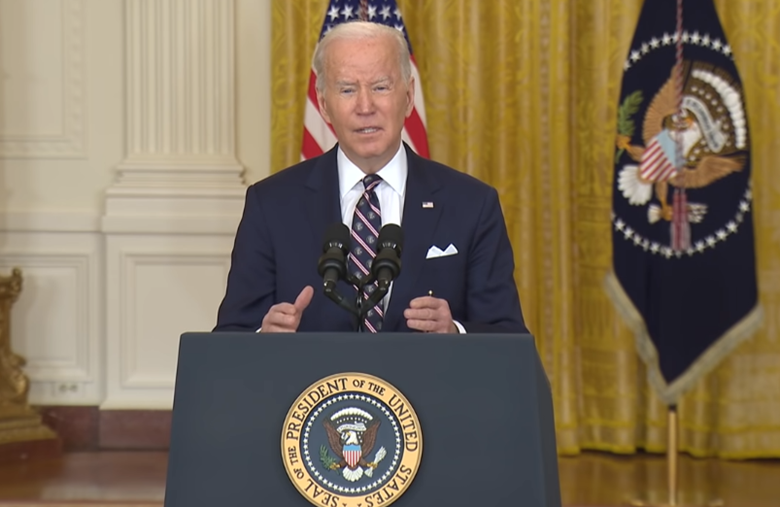

Is Putin testing the waters for a wider invasion? Biden seems convinced, although he said he hoped he was wrong. U.S. intelligence just weeks ago was saying there would be a major invasion of all of Ukraine — a notion that Ukraine visibly pushed back against the past several weeks — with Western countries seen evacuating non-essential diplomatic personnel from Kyiv. Biden said on Jan. 25 it would be “the largest invasion since World War Two.” It wasn’t. Not yet, anyway.

On the other hand, Biden isn’t saying this was the expected attack and that a larger attack could still loom. Biden on Feb. 22 said that this is only “the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine” and “We still believe that Russia is poised to go much further in launching a massive military attack against Ukraine”. Since 2014, the conflict has largely been centered in these Russian-speaking breakaway provinces.

But is that where it will end?

Time will tell. By explicitly taking force off the table and instead offering sanctions and pipeline approval pauses, the U.S. and the allies appear to lack sufficient deterrence to protect the non-NATO allies including Ukraine.

In the meantime, barring a full-scale invasion, then, the failed Minsk accords are now elevated in importance. In 2014 and 2015, those talks were a lifeline that attempted at least to mitigate the crisis with a ceasefire and periodic talks between Ukraine and Russia, mediated by France and Germany. Diplomacy, even at this late hour, now may be the only way to avoid a wider war. It’s not too late to turn back from the brink. But does anyone else want to talk?

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.

A version of this article appeared on algresearch.org.