The combination of the $30.4 trillion national debt and the strong dollar underscore both the advantages and the perils of the U.S. dollar’s so-called “exorbitant privilege” as the world’s reserve currency.

That is, when the economy is in turbulent waters and a recession appears to loom, financial institutions and central banks all over the world will tend to jump into U.S. treasuries in a flight to safety, as they are doing now.

Consider 10-year treasuries, where despite 8.3 percent consumer inflation and 11 percent producer inflation for the past twelve months, remarkably, rates have been falling, from about 3.12 percent in early May to about 2.8 percent now as of this writing as financial markets have been roiled by the simultaneous supply chain crisis pressures, the sagging U.S. economy and the war in Ukraine.

This ultimately pushes U.S. interest rates down, and the Federal Reserve will tend to follow suit in cutting rates once a recession has been realized. In recent years, since the financial crisis, this practice has also been accompanied by steady purchases of U.S. treasuries to keep rates low.

This in turn makes it cheaper to finance the U.S. national debt, especially through massive government spending. This year, the White House Office of Management and Budget projects the deficit will top another $1.4 trillion for 2022, after record $3.1 trillion and $2.77 trillion deficits in 2020 and 2021, respectively.

And so, why would Congress ever want to cut spending? All leaders in Washington, D.C. have to do is keep the spigots on, creating an ever-larger supply of marketable U.S. treasuries in order to keep their perpetual money machine working.

It’s a perverse incentive. Just watch when the next recession strikes. Once the unemployment rate starts rising, the pressure will similarly increase for Congress to stimulate the economy with more spending. In some ways, it won’t even need to, since revenues take a hit during recessions anyway, and so, the deficit — and thus the supply and demand for treasuries — tends to rise all on its own.

In years past, and even after the financial crisis, which saw Congress expend some $700 billion for the Troubled Asset Relief Program and then another $900 billion for the Obama stimulus, rampant inflation was avoided when control of the House switched to Republican control in 2010. This set the stage for a battle over increasing the debt ceiling, which then-House Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio), with backing from Tea Party Republicans who were elected that year, was able to secure a deal on budget sequestration.

It worked. The deficit had peaked at $1.4 trillion in 2009, and by 2015, it had dropped to just $441 billion, just by essentially freezing defense and non-defense discretionary spending via budget sequestration.

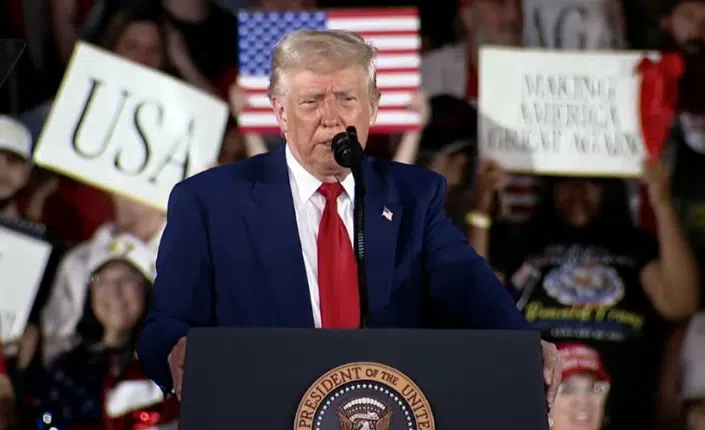

The same thing might happen in 2023, with President Joe Biden being a potential beneficiary of tapping on the brakes fiscally. Readers will recall that in 1994 and 2010, Democratic Presidents whose Congress’ had overstepped lost control of one or both houses of Congress, only to go on to be reelected in 1996 and 2012, respectively.

Voters tend to favor mixed government at times as a means of mitigating each of the parties’ excesses, especially runaway presidential administrations that appear out of control. That factor will favor Republicans in 2022, where the GOP still leads Democrats in the Real Clear Politics average of polls in the Congressional ballot by 1.9 points, 46 percent to 44.1 percent.

Here and now, the American people appear to be saying, it’s time for a change.

Should Republicans prevail in November, as is likely in a midterm cycle with the GOP out of power, once gridlock sets in again in Washington, D.C. in 2023, and spending slows down, should the supply chain crisis be resolved and inflation comes down, the public’s desire for mixed government might subsequently work against Republicans in 2024.

On the other hand, should the supply chain crisis worsen and economic turmoil carries over into 2023 and beyond, a repeat of the 1970s and early 1980s’ stagflation, all bets could be off for Biden in 2024, should he even run again. Weakness is provocative, and so something to watch for will be primary challenges that could ultimately push an old president who ran out of luck — out of power — as happened to Lyndon Johnson in 1968. Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.