By Rick Manning

What is the state of the labor force in America on Labor Day 2023?

It is transitioning. More and more employers who were previously embracing the work from home model are now demanding that employees come back to the office, and employees who like the freedom of working from home aren’t happy.

Amazon’s CEO has bluntly told employees who defy the company’s return to office mandate that it “won’t work out well for you.”

A quote from an Amazon employee blog reported on CNBC encapsulates the attitude of many who are fighting to keep their work from home privileges, “By arbitrarily forcing return-to-office without providing data to support it and despite clear evidence that it is the wrong decision for employees, Amazon has failed its role as Earth’s best employer. I believe this decision will be detrimental to our business and is antithetical to how we make decisions at Amazon.”

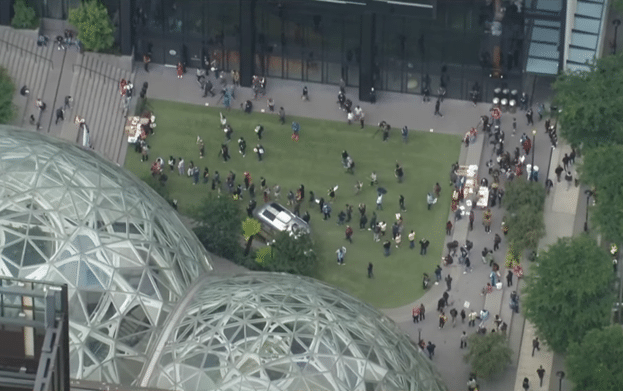

Employee petitions have been created with thousands of signatures by people who honestly think that Amazon’s senior management needs to have and comply with a democratic vote in the company on whether they should return to the office a minimum of three days a week.

Let’s be clear. The employees have a right to not comply, and Amazon has the option of whether to continue allowing them to have remote access to their internal computer systems and a paycheck. Gen Z and Millennial America are going to discover a simple truth that they are free to work from home, they just may not be able to do so for their current employer. And what their future employer may be willing to pay for homeworkers will likely be based upon defined performance standards.

The fact that Amazon is making this decision reveals a shift in how their management (and others like Elon Musk at X) view both the quality and quantity of work being done by their remote workforce and their belief that they can replace those workers who fail to comply.

Over the past nine years, absent the short Covid recession, the number of job openings have significantly exceeded the number of people in the labor market to fill them. That is rapidly changing.

The U.S. Labor Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics measures the numbers of unfilled jobs and compares that number to the number of people looking for a job. In July of 2022, there were more than 10.3 million private sector job openings, by July of 2023 that number has dropped to almost 7.9 million. The most recent August employment report found that there are 6.4 million unemployed. A far cry from the 2 jobs for every unemployed person that had become the new normal just a year ago.

The narrowing gap between jobs available and the number of unemployed has a psychological impact. It tells employers that finding replacement employees for relatively high paying jobs should be easier. It tells employees that the next job might not be as easy to replace as the one they have, particularly at the pay range they expect.

This shift rebalances the power dynamic between labor and employers and undoubtedly emboldens employers like Amazon and X to reclaim the power to directly oversee the activity of their employees.

But this is not just a power play. Worker productivity plummeted in the first quarter of 2023, making the fifth straight quarter of productivity losses. The second quarter showed a rebound breaking the unprecedented losing streak, but employers who once wholeheartedly endorsed work from home now likely see a return to the workplace as a solution to the higher costs per unit produced problem.

It is reasonable to presume that Amazon and other major companies around America have discovered the obvious: unmonitored employees as a whole are not as productive as one’s who are in the office. If this were not true, tech companies in particular would be selling their office space, ending plans for campus growth and cutting big ticket fixed capital costs to enhance profits.

And remote employees will not easily give up the perks of working from home after having become accustomed to shifting household costs away from daycare, gasoline and sometimes even housing as they adapted to the new work from home environment encouraged post-Covid.

Those who feel their lives are being turned upside down by employer expectations that they return to the office are not wrong. They have worked in their home environments for three years. And employers who are suffering from diminished productivity from their at home workforce are not wrong to expect that employees will work and focus on the company’s priorities.

But one aspect of this remaking of the American workplace that is make or break for business is the idea that employees have a right to dictate internal corporate employment policies as demonstrated by the aforementioned blog post from an Amazon employee.

Employees have a right to leave a company if they don’t like working conditions, benefits, pay or the attitude of their bosses, but companies have a responsibility to their shareholders to make profits. Working from home is a privilege, and allowing those who benefit from that privilege to dictate corporate employment policy would be a disaster.

Even a company like Amazon needs to be able to provide their products and services in a cost-effective way, or else someone else will do it faster and cheaper. Every company is a few mistakes away from becoming MySpace, and when those decisions are outsourced to employees whose only concern is whether they can work from their couch or not, the company is doomed to fail.

The fallout from Covid has not been entirely felt in our nation. The ability to work from home has created a number of opportunities for those who are homebound, disabled or partially retired. But it is time for a vast majority of America to get back to work — petition signatures notwithstanding.

Rick Manning is the President of Americans for Limited Government.