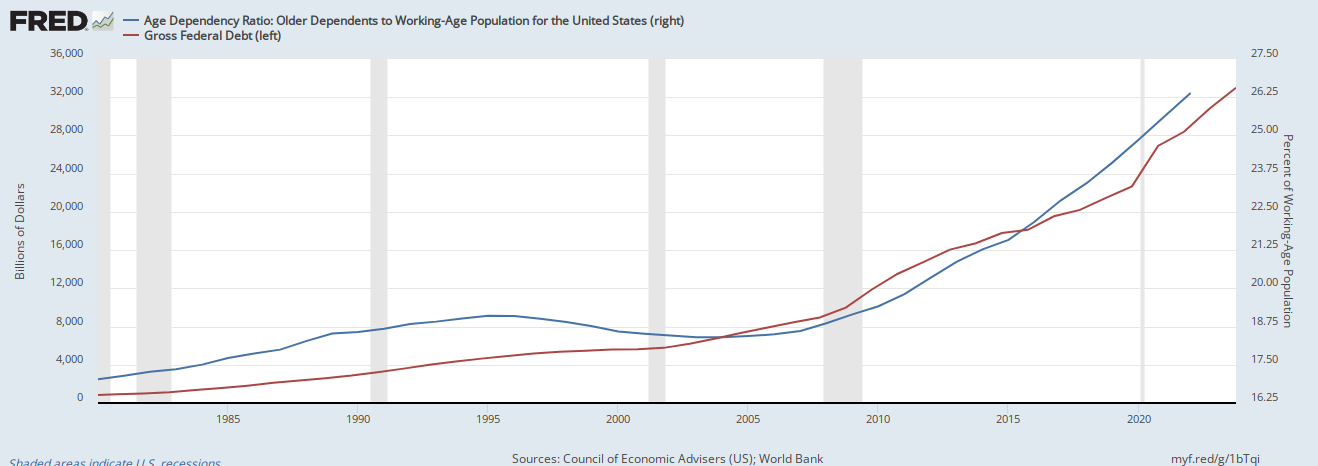

As the Baby Boomer retirement wave continues apace, the percentage of the working age population over the age of 65 continues to rapidly increase—since 1960, it has gone from 16 percent of the population to 26 percent of the population—and with it the $33 trillion (and rising) U.S. national debt, data from the World Bank and the U.S. Treasury shows.

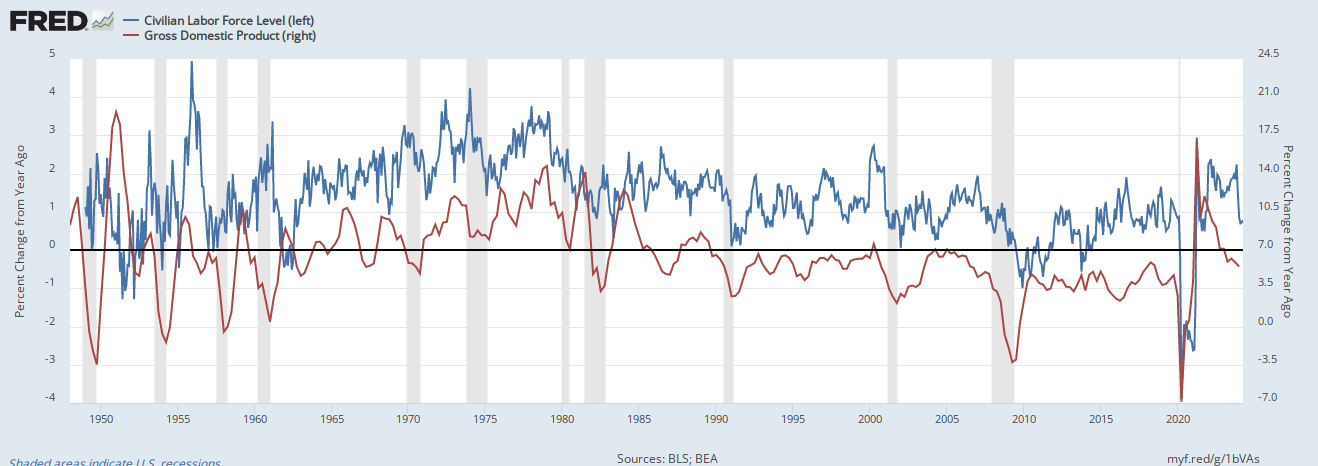

At the same time, as the growth rate of the working age population participating in the civilian labor force has dramatically slowed down thanks to plummeting fertility, so has nominal economic growth, Bureau of Labor Statistics and Bureau of Economic Analysis data shows.

There are two simultaneous outcomes that emerge. First, as the population rapidly ages, so too do Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid expenditures that seniors depend on. Social Security will rise from $1.2 trillion in 2022 to $2.4 trillion in 2033, according to the White House Office of Management and Budget. Medicare will rise from $747 billion in 2022 to $1.8 trillion in 2033. And Medicaid will rise from $592 billion in 2022 to $926 billion in 2033.

In the meantime, and second, thanks to slower growth, revenues will in no way keep pace with expenditures. Revenues will increase from $4.9 trillion in 2022 to $7.4 trillion, a $2.5 trillion or 51 percent increase over ten years. But expenditures will grow even faster, with outlays growing from $6.2 trillion in 2022 to $9.9 trillion by 2033, a $3.7 trillion or a 58.6 percent increase over the next decade.

If you find yourself saying to yourself “That’s not sustainable” then you might ask yourself how many kids you and your neighbors had, because the structural deficit is widening simply due to the drop in fertility, which has been primarily a result of birth control since 1960.

Fewer babies equals fewer workers who pay taxes. The more people who retire, the more we spend, and the fewer people working per retiree, the more we borrow. It’s that simple.

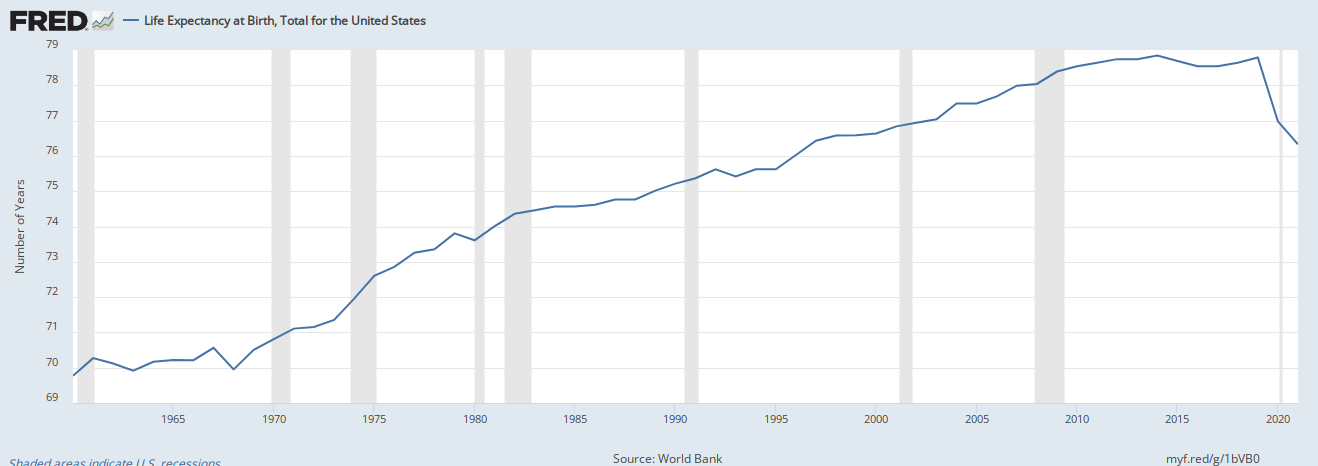

Yes, life expectancy has increased, but that would have mattered less if the Baby Boomers, Generation X and Millennials simply had more children. If we could have simply kept up with population replacement, this wouldn’t be as much a problem, as evidenced by balanced budgets emerging in the 1990s when the retiree to worker ratio dropped for a few years.

Knowing this problem, policymakers, rather than finding an ounce of political courage to implement policies that might incentivize women to have more children via tax credits or some other means, resort to opening the floodgates of immigration to offset a population seemingly bent on its own extinction through omission. Similarly, Malthusians and other green activists are okay with this outcome because then we can “save” the planet by slowing carbon emissions and conserving resources.

Every year, Congress nibbles around the edges of taxes and spending policies, addressing less than one-third of the total budget via so-called discretionary spending. In 2022, the $1.6 trillion discretionary budget amounted to 26.5 percent of the $6.2 trillion overall budget. By 2033, that will drop to 23.8 percent, or $2.37 trillion out of the $9.9 trillion budget.

By then, the budget deficit will be more than $2.5 trillion every single year. At that point (or even now for that matter), you could eliminate every department and agency in the federal government including the Department of Defense, and we would still be unable to balance the budget.

Every year we ignore the fertility crisis it gets worse. The debt has grown by about 8 percent a year since 1980 once recessions and wars are factored. At that rate, it should be about $100 trillion by 2037 or so, well north of 200 percent debt to GDP. When Congress comes to cut your benefits or raise everyone’s taxes or both, realize that the outcome was largely avoidable. To future generations who might read this missive, assuming fertility doesn’t go all the way to zero, be fruitful and multiply, or this is what happens.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.