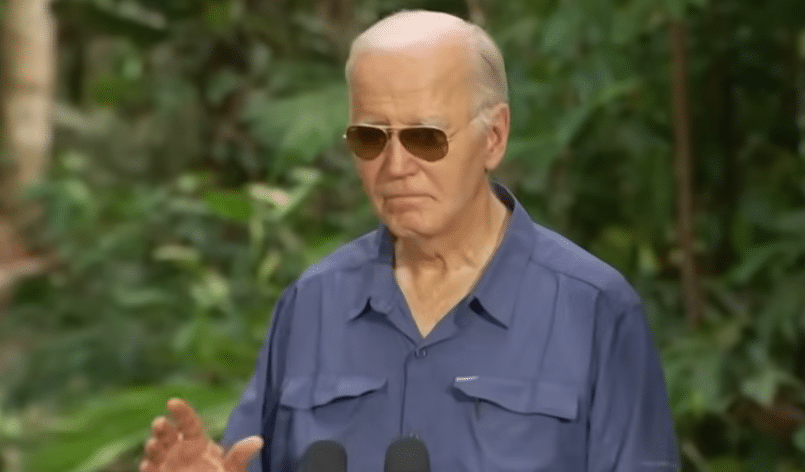

President Joe Biden is attempting to lock in U.S. support for Ukraine in its ongoing war against Russia following Russia’s Feb. 2022 invasion of Ukraine and more recently, the U.S. reelection of former President Donald Trump, who is set to take office Jan. 20, 2025, with Biden approving the use of U.S. missiles against targets directly in Russia on Nov. 17, as well as greenlighting what remains of the current tranche of military funding for Kyiv.

In response, Moscow has changed its nuclear weapons doctrine on Nov. 19, alerting the West that any country used as a proxy to launch direct attacks into Russia will be considered an attack by that proxy’s supporting nuclear states. Specifically, the executive order, archived by Web Archive and signed by Russian President Vladimir Putin, translated by Google, states, “Aggression by any state from the military coalition (bloc, alliance) against the Russian Federation and (or) its allies is considered as aggression of this coalition (bloc, alliance) as a whole…” and “Aggression against the Russian Federation and (or) its allies by any non-nuclear state with the participation or with the support of a nuclear state is considered as their joint attack.”

Additionally, the doctrine warns that “The conditions determining the possibility of using nuclear weapons by the Russian Federation” include “receipt of reliable information about the launch of ballistic missiles attacking the territories of the Russian Federation and (or) its allies” and “aggression against the Russian Federation and (or) the Republic of Belarus as participants in the Union State with the use of conventional weapons, creating a critical threat to their sovereignty and (or) territorial integrity…”

The doctrine also warns, “Nuclear deterrence is aimed at ensuring that a potential adversary understands the inevitability of retaliation in the event of aggression against the Russian Federation and (or) its allies.”

Those are “possible” triggers for the use of nuclear weapons by the Kremlin, and although it warns of the “inevitability of retaliation,” the document also states, “The decision to use nuclear weapons is made by the President of the Russian Federation.” So, the potential triggers are not mandatory and Putin alone might be the one to decide when an attack leads to “inevitable” retaliation.

Undeterred, with that predicate, Ukraine launched the U.S. missiles, Army Tactical Missile System (Atacms), into Russia on Nov. 19 anyway, presumably with President Biden and NATO’s blessing.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky justified the missile strikes saying that actions speak louder than words, and that “Missiles speak for themselves.”

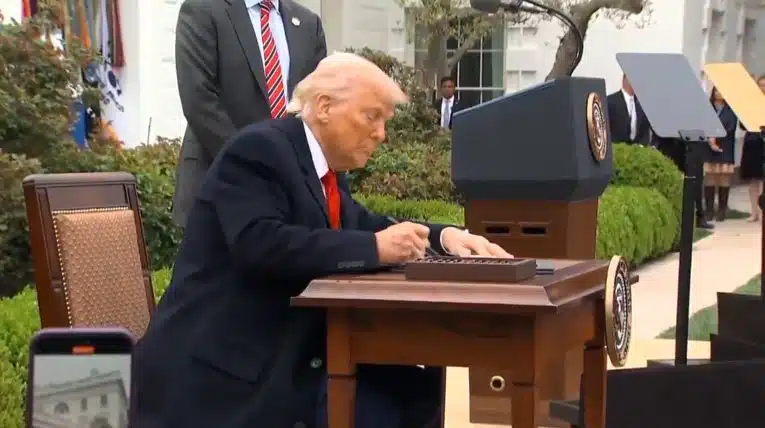

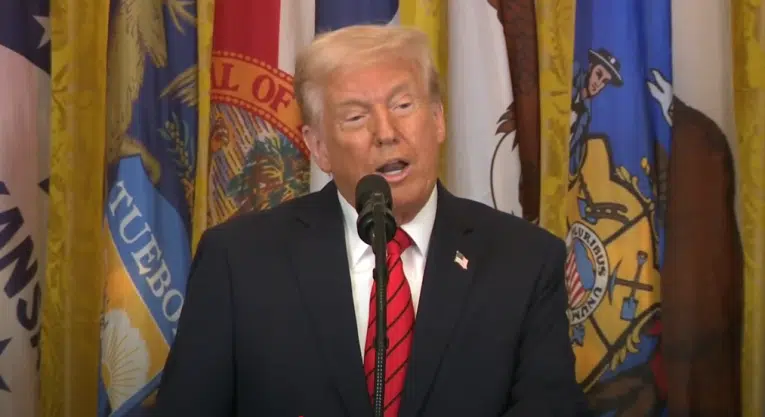

In the meantime, President-elect Donald Trump, who openly campaigned against the war in Ukraine, has called for a negotiated, diplomatic settlement. In the Sept. 10 debate with now-defeated Vice President Kamala Harris, Trump blasted Biden’s no-contact-with-Putin strategy: “He hasn’t even made a phone call in two years to Putin. Hasn’t spoken to anybody. They don’t even try and get it. That is a war that’s dying to be settled.”

Trump predicted he could get it settled as President-elect, stating, “I will get it settled before I even become president. If I win, when I’m President-Elect, and what I’ll do is I’ll speak to one, I’ll speak to the other, I’ll get them together.”

Trump also warned that the war could lead to nuclear holocaust: “That war would have never happened… And now you have millions of people dead and it’s only getting worse and it could lead to World War 3. Don’t kid yourself, David. We’re playing with World War 3. And we have a president that we don’t even know if he’s — where is our president? We don’t even know if he’s a president.”

To summarize, in the middle of the presidential transition to Trump, who wants to negotiate an end to the war in Ukraine, Biden escalated the war. Whether that strengthens Trump’s hand in the negotiation, or locks in the U.S. position as Congress will seek to require U.S. intervention as it did during Trump’s first term, particularly on the issue arming Ukraine, remains to be seen.

Last time, the issue of arming Ukraine was made infamous by the 2016 Russiagate scandal — the Democratic National Committee and the Hillary Clinton campaign paid former British spy Christopher Steele to fabricate sources to say Trump was Russian agent who helped Moscow hack the DNC and John Podesta emails and put them on Wikileaks, and that part of the supposed deal was for Trump to withhold arms from Ukraine.

Naturally, that gave Congress leverage against Trump to say, if you don’t approve arms to Ukraine, you must be a Russian agent. And so, despite campaigning in 2016 against escalating the war in Ukraine — by then, former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych had been overthrown in a U.S. backed action and Russia had annexed Crimea in response in 2014 — Trump after taking office signed into law the appropriations providing the arms to Ukraine, escalating the U.S. role.

But, in 2019, when Trump considered putting conditions on the weapons that were being sent to Ukraine, the then-Democratic House immediately impeached Trump, who was later acquitted by the U.S. Senate.

Still, as Trump noted on the campaign trail in 2024, Putin did not launch the full-scale invasion of Ukraine until 2022, after Trump had left office. Whether that was due to deterrence or just timing is a good question, but Trump has stated he had threatened to attack Russia to protect Ukraine, claiming in a 2022 phone call with golfer John Daly, “he was a friend of mine… I got along great with him. I say, ‘Vladimir, if you do it, we’re hitting Moscow. I said, ‘We’re gonna hit Moscow.’”

Trump added, “I said, ‘We’re gonna hit Moscow… And he sort of believed me, like five percent, 10 percent. That’s all you need.”

Now, the U.S. via Ukraine is actively hitting Russian targets inside Russia. The same questions emerge: Is Russia deterred? No, the invasion continues. So, if hitting the Russian targets does not carry a deterrence value, then on the other hand it could carry the risk of escalation, provocation and retaliation.

It reminds of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, which was ultimately resolved by John Kennedy and Nikita Khruschev by agreeing to withdraw nuclear missiles from Cuba and Turkey, the first ever nuclear arms reductions. That paved the way for further arms limitations in the 1970s, 1980s and 2010s, including the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties, the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty and the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties (START). Of those, only the START treaties, which superseded SALT, remain, with both the ABM and INF treaties gone.

So, sometimes a potential nuclear standoff being averted can set the stage for new diplomacy. A similar situation played out during the Trump administration vis a vis North Korea, a nuclear threat that ended up with face-to-face meetings between Trump and Kim Jong Un.

The options being talk, or fire, Trump seems apt to choose to talk as a first resort.

Trump is a potential wild card in terms of being a diplomatic negotiator — this time he is not hampered by a Special Counsel as Jack Smith is preparing to leave office — does that cause Russia to wait for the new administration to settle the Ukraine question? With the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists saying there are just 90 seconds left until midnight for thermonuclear war, the closest it has ever been since the clock was adopted in 1947, time is running out.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy of Americans for Limited Government Foundation.