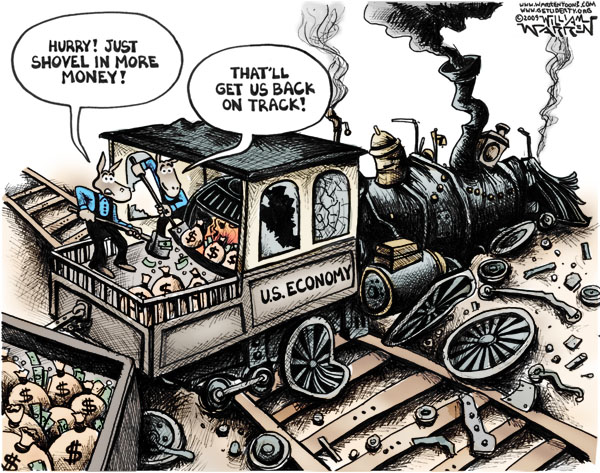

“It’s just debt for debt’s sake, not to help build future production or earnings, but to simply fuel consumption.”

That’s how Americans for Limited Government (ALG) President Bill Wilson described the latest scam by government and financial institutions to boost “growth.”

Having exhausted the market for crappy loans in housing and college students, now banks are turning their attention to the rapidly growing industry of subprime auto loans — that is, loans to borrowers with bad credit, yielding higher interest rates, and are more likely to default.

“Consider that in 2012, lenders sold $18.5 billion in securities backed by subprime auto loans, compared with $11.75 billion in 2011, according to ratings firm Standard & Poor’s,” Reuters reported on April 7.

The story led with a Jasper, Alabama man, Jeffrey Nelson, who got a $10,294 loan for a 2007 Suzuki Grand Vitara with a $300 down payment and using a shotgun valued at $700 as collateral. The result was a $324-a-month payment and a 21.95 percent interest rate.

Nelson is now bankrupt and divorced, and his ex-wife, who has assumed the car payment, expects she’ll be filing for bankruptcy soon, too.

“These subprime auto loans prove just how desperate the Federal Reserve is to create credit in this stalled economy,” remarked ALG’s Wilson.

Wilson pointed to data from the Federal Reserve and the Bureau of Economic Analysis showing a strong relationship between credit creation and what he called “the illusion of economic growth.”

“From 1946 to 1970, credit outstanding nationwide, that is, all debts public and private, grew at an average rate of 6.25 percent. The economy more than kept pace, nominally growing at 6.5 percent a year,” Wilson noted. “Back then, credit creation was predicated on economic growth.”

But then history changed. “Richard Nixon abolished the Bretton Woods gold exchange standard, and with no constraint on the amount of dollars that could be created, credit exploded. From 1971 to 2007, public and private debts grew an average 9.8 percent a year. During that time, the economy seemed to grow faster at 7.3 percent.”

That is, until the debts started going bad, the housing bubble collapsed, credit contracted, banks were bailed out, unemployment skyrocketed, and the recession began. “Now,” Wilson noted, “the average rate of nominal economic growth since 1971 has dropped to 6.7 percent.”

In other words, GDP is more or less basically where it would have been without all of the additional debt.

“The lesson is that there are no shortcuts to prosperity. All excessive credit achieves are temporary boosts to economic activity, and then when the bubble pops, those gains are eroded,” Wilson noted.

To wit, the only thing really achieved is the accumulation of a lot of debt, Wilson added. “In 1970 credit outstanding as a percent of the economy was 152 percent. By 2008, when the bubble popped, it peaked 373 percent of the economy when it hit $53 trillion.”

Now, credit creation has slowed down, and with it the economy. In the past four years credit outstanding has only averaged 1.4 percent growth. “In 2012, it did pick up a little, growing at 3.3 percent, but it’s nowhere near its pre-crisis pace of 9.8 percent a year,” Wilson said.

And it’s an open question whether the economy, so addicted to credit, can robustly grow without that additional stimulus, Wilson added.

So, lenders are now being called on to extend more credit to boost economic activity. And the fastest way to expand debt is to weaken lending standards. Therefore, subprime auto loans.

Except, at $18.5 billion, the market for such loans is not nearly large enough to really get credit markets moving again — which to hit 9.8 percent growth will require more than $5 trillion of new debt a year.

The same problem faces mortgage lending, with originations way down. “The problem in the housing market is not a lack of lending capacity, which is virtually limitless as banks are sitting on $1.6 trillion of excess reserves,” Wilson noted. “It’s that even with it as easy as it is to get a loan, demand is still very low, and therefore it’s not easy enough for the central planners, so the push becomes to lower credit standards.”

For all the alleged good intentions of letting people borrow money they have no capacity to repay, it’s important that we remember the regret and pain this caused Jeffrey Nelson, a man who couldn’t say no when someone pushed a “too good to be true” deal in front of him.

As this story is repeated tens of thousands of times, with 6.6 million subprime auto loans outstanding according to Equifax, one wonders how much more heartache is ahead as purveyors of easy money attempt to manipulate markets.

Robert Romano is the Senior Editor of Americans for Limited Government.