On Memorial Day we remember and honor that one brother who gave his all for his country.

Augustine “Augie” Leonardi, 1918-1944

To paraphrase Gen. Douglas MacArthur, I do not know the dignity of my great uncle’s birth, but I know the glory of his death. My great uncle Augustine Leonardi was born in Pueblo, Colorado on August 4, 1918, far from the battles raging in Europe during the First World War. His father was a first-generation immigrant from Austria who came to America in search of a better life and ended up owning a saloon in a mining town in northern New Mexico before moving his family to nearby Pueblo in search of better work after the mine closed.

Augustine, who was known as “Augie,” was the sixth of nine children. Augie’s father died when he was only six years old. When he was twelve, his mother passed, as well. For a time Augie and his siblings lived with their oldest brother in Trinidad, Colorado before eventually moving to Salt Lake City where they were raised by their maternal grandmother, the widow of a Civil War veteran from Massachusetts.

On October 17, 1941 Augie enlisted in the Army. He was 24-years old. On that same day German troops were within 60 miles of Moscow and the USS Kearney became the 1st US destroyer torpedoed in World War II, despite the country still officially neutral. Two months later, after the Dec. 7 Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. entered the war. Augie’s younger brother, Constantine, “Const,” also enlisted. Six months later, one of their older brothers, Leo, also enlisted. Leo was sent to the European theater where he would take part in the liberation of Italy. Augie and Const were sent to the Pacific where they served under Gen. MacArthur.

In the spring of 1944 Augie and Const were serving on Biak Island, New Guinea. Const wrote a letter home to his sister Thelma in Salt Lake City telling her that he was “taking it easy,” and wanted to make sure their grandmother got the war bonds he sent her. He also shared that he’d just learned that one of their relatives through marriage was also serving in New Guinea. Const closed his letter saying, “bye for now, but don’t you worry because before you know it, we’ll be home. I hope you take good care of grandmother until we return.”

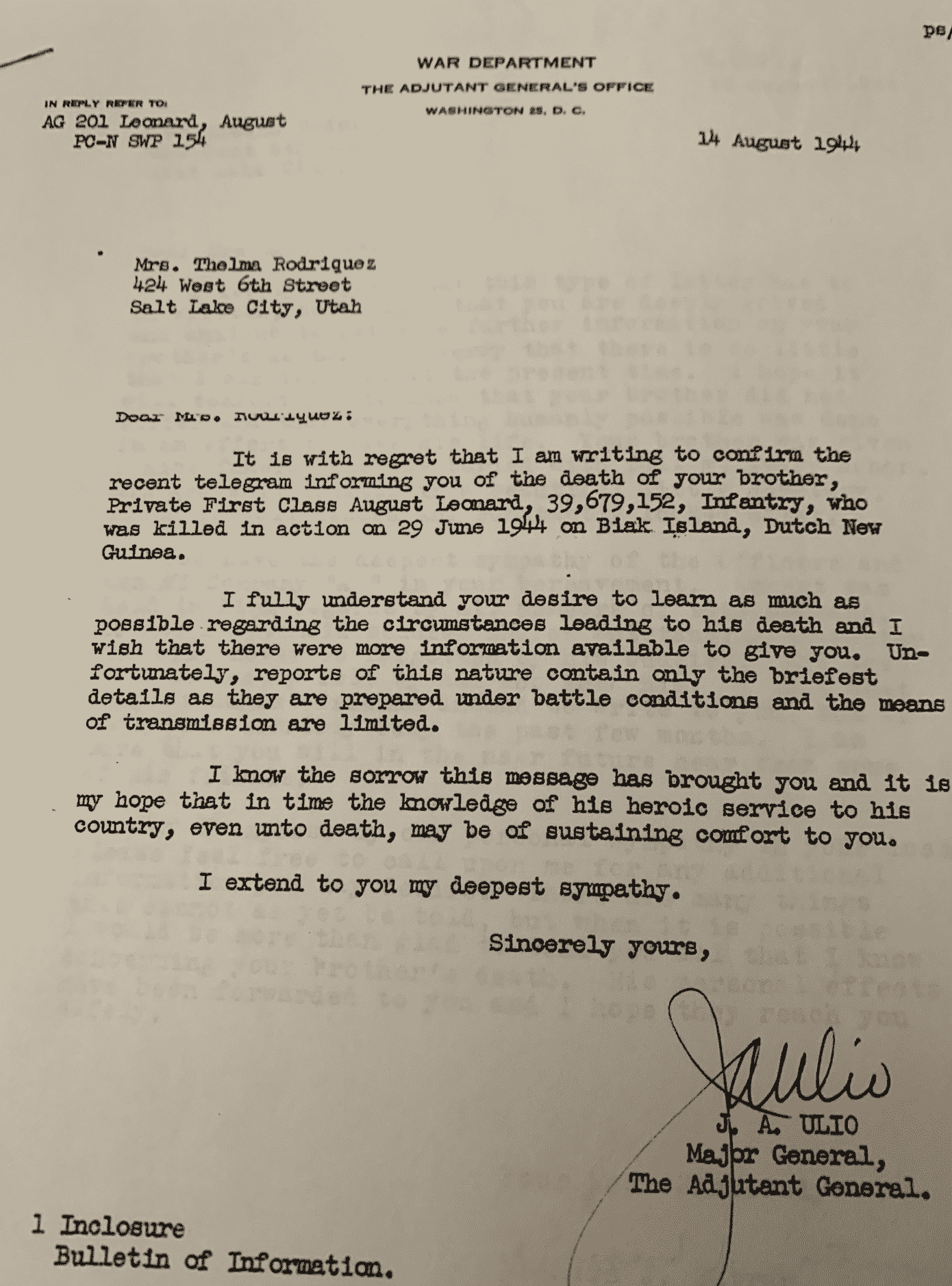

Letter from the Department of War to the family of Augustine Leonardi telling them of his death in the Battle of Biak in New Guinea.

Two months later on June 29 Augie was killed in the Battle of Biak, in an effort to take the island from the Japanese. Writer David Alan Johnson of the History Network writes that this was one of the bloodiest battles in the Pacific.

“Soldiers went about the business of clearing the caves with grim determination. Some used flamethrowers, crawling within point-blank range of the entrance under the cover of rifle fire and burning out the cave interiors with long streams of fire. Sometimes the flames would hit one of the cave walls and bounce back at the Americans.

“Flamethrowers were unable to reach far enough inside some of the larger caves. Satchel charges, hand grenades, and gasoline were usually employed for these. Gasoline was sometimes poured into one of the openings and then set on fire. After a few minutes, dull thuds and rumblings could be heard coming from the cave’s interior—ammunition supplies were exploding, destroying the cave along with everyone inside it.

“The effect of satchel charges was every bit as horrific as that of gasoline. After one cave was blown apart, a private went inside to see what was left. He came out a few minutes later, nauseated and vomiting. ‘My God, it looks like a scene from hell,’ he said. ‘Pieces of men all over the tunnel floor! Bodies with bellies blown open by concussion! Blood running from the ears, noses, mouths, and eyes of dead [Japanese! It’s awful!’

“Col. Harold Riegelman had the chance to take a look around the vicinity of the West Caves and spoke with some of the men who had been engaged in the heavy fighting. He was matter of fact in his evaluation. ‘I saw the disabled Jap tanks, inspected a nearby mortar platoon, talked to the men, noted their drawn, bearded faces and eyes, red from lack of sleep. They did not complain.'”

That is the glory of my great uncle’s death. He died two months shy of his 26th birthday doing unspeakably hard things in the defense of liberty and freedom and he “did not complain.” He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart Medal and is buried at Fort William McKinley in the Philippines. His brothers both returned home to raise families and quietly, without any honors, helped contribute to the greatest economic success story in all of humankind, America’s post-War economic boom.

In MacArthur’s 1962 speech to the Corps of Cadets at West Point he paid tribute to the American soldier calling him, “one of the world’s noblest figures. When I think of his patience under adversity, of his courage under fire, and of his modesty in victory, I am filled with an emotion of admiration I cannot put into words.”

My father was just five years old when his uncles returned from the war. He revered them and wanted to hear their war stories. “I would ask them for stories, but they didn’t talk about it much. Though one uncle gave me a German Lugar that my brother and I took to school for show-and-tell,” he recalled.

“They did what they were asked to do,” my dad said. “That was their duty and they met it.”

May we always remember with reverence and gratitude those brothers who never came home.

Catherine Mortensen is Vice President of Communications for Americans for Limited Government.