By Manzanita Miller

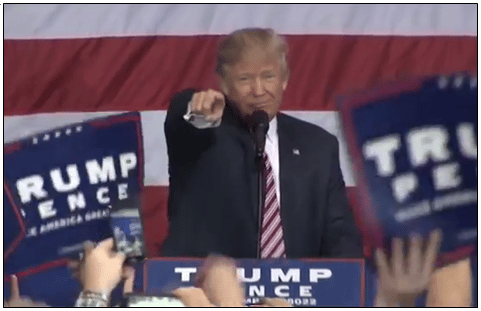

Former President Trump has no doubt altered the Republican Party since he entered the political arena in 2015, but he has also given rise to a new form of conservative populism that has yet to be captured entirely by polls and political analysts.

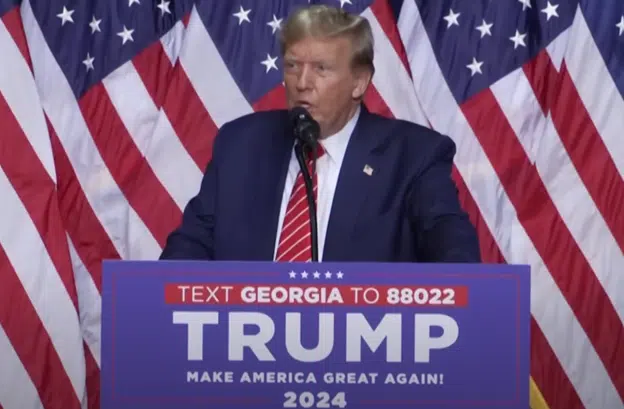

Michael Tesler, a professor of political science at University of California, Irvine, recently made the case in a Five Thirty Eight article that former President Trump has redefined what it means to be a conservative, and that the label now essentially means, “pro-Trump” and little else.

Tesler goes over a dearth of polling data showing that since Trump’s unexpected entry into the political sphere in 2015 and even more unexpected victory, the way the term conservative is used has changed.

Early in Trump’s political career, he was largely rejected by the Republican political class, and particularly by those who identified as conservatives. In his article for Five Thirty Eight, Tesler references a 2015 edition of National Review which was published just ahead of the GOP primaries with a stark anti-Trump message. The magazine published a series of letters from influential conservatives arguing that Trump’s campaign was “a menace to conservatism”. Trump was largely portrayed as an outsider, inexperienced, and a threat to the delicately ordered set of priorities that defined conservatism in the immediately post-Obama era.

Tesler outlines the fact that in a 2016 Quinnipiac poll, just 27% of GOP leaning voters who identified as “very conservative” said they supported the president, while the most recent Quinnipiac poll shows a full 61% of “very conservative” voters support Trump, an increase of 34 percentage points compared to 2016.

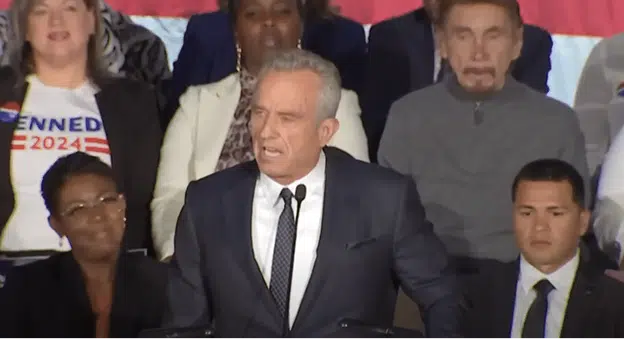

The argument that the term conservative has shifted to mean pro-Trump is an interesting one, but it is also possible that the term conservative is simply becoming less relevant overall. The reality is Trump is more of a populist; however, most Americans aren’t self-identifying as populists.

Only in certain highly active political circles are a few more pioneering political minds adorning themselves with the populist label. The term is largely relegated to the worlds of political analysis and academia – not to voters’ view of themselves. Not only that, but pollsters rarely if ever add the option of populist as an ideological label on surveys. Most surveys simply ask whether a voter is a liberal, moderate or conservative, occasionally adding options for ‘very liberal’ and so forth.

However, this does not render the concept of populism any less relevant to capture political sentiment and the shift toward a more inward-focused set of national priorities compared to previous time periods.

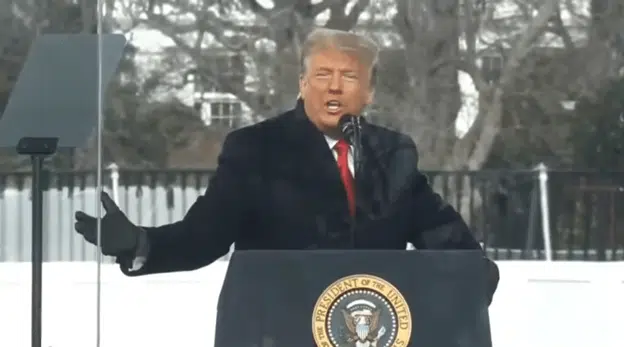

When ideological conservatism is left off the table and GOP primary voters and those who lean Republican are asked whether they believe it is important to “restore the policies of the Trump Administration”, a vast majority say it is. A late March CNN/SSRS poll shows that GOP primary voters say 85% to 15% that it is important to restore Trump-Administration policies. Female GOP primary voters (86%), voters with income under $50,000 (87%) and white-non-college voters (91%) say restoring Trump-era policies are important at the highest rates.

The same poll shows that opposing foreign-intervention, one of the stances Trump has been criticized for most by more conventional conservatives, is extremely important to GOP primary voters. Voters say 80% to 20% that it is important the GOP-primary pick opposes U.S. involvement in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and women (87%) and young people (83%) hold these views at the highest rates.

These findings come at a time when a significant anti-war sentiment is prevailing among the public, particularly on the right. Recent polling reveals that more than half of Americans oppose providing weapons to Ukraine, and support for continued weapon supply has dropped from 60% in May 2022 to under half (48%) in February of this year.

Furthermore, nearly three-quarters of Americans believe that the U.S. should have either a minor role (49%) or no role at all (24%) in the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Only 26% of respondents advocate for a major U.S. role. It’s worth noting that a higher proportion of Democrats (40%) than Republicans (17%) support a major U.S. role, although both figures have decreased compared to previous polls.

Polls already indicate a shift in public sentiment on immigration, as a plurality of Americans now call for a reduction in immigration for the first time in decades. Gallup polling reveals that two-thirds (63%) of Americans express dissatisfaction with immigration, the highest percentage in over ten years. Notably, the dissatisfied group is primarily driven by those who desire decreased immigration levels, constituting 40% of Americans. In contrast, only 8% wish to expand immigration. The proportion of Americans seeking decreased immigration has more than doubled in just two years, rising from 19% in early 2021 to the current 40%.

What this boils down to going forward is somewhat intuitive, but no less important for attempting to accurately identify political shifts. The post-Obama era of conservatism in 2015 was a distinctly different form compared to the Trump-era conservatism.

Trump awoke a blend of conservative populism, defined by socially conservative values combined with anti-foreign intervention and a desire to secure the border and focus on an inward set of priorities. Some of these stances can be found in pre-Trump conservatism. For instance, pro-life issues were always important to GOP voters and are a growing aspect of modern conservatism. But other stances – like strongly opposing foreign intervention – are new territory for the status quo Republican Party and using the label “conservative” to define them doesn’t entirely fit.

Manzanita Miller is an associate analyst at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.