Anyone sending their kids to college nowadays or paying off their student loans has probably noticed that the costs are out of control.

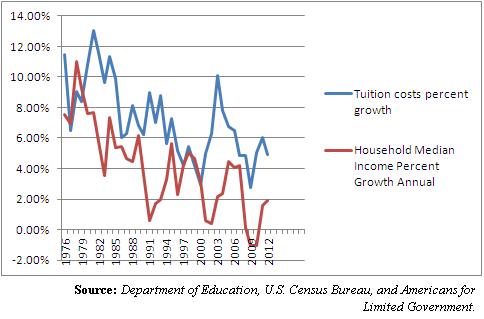

In fact, tuition is consistently outstripping the growth of incomes. Since 1976, annual college tuition public and private has increased 1,056 percent — from $924 to a current level of $10,683, according to the Department of Education. That is more than 7 percent growth a year.

Meanwhile, household median income has increased just 302 percent, or 4 percent a year, from $12,686 to the current level of $51,017, according to data compiled by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The risk of going to college is that increasingly you might not find a job that pays for it at the end of the rainbow.

In fact, nearly half of four-year college graduates say they are not even working in professions that require a bachelor’s degree, according to a 2013 study of 4,900 college graduates by McKinsey & Co. Another third said that college had not prepared them properly for the working world.

As it stands now, annual tuition is about $10,000, and growing at an average rate of 7 percent a year. In just 14 years, holding to the historical average, annual tuition should be about $26,000 a year, or $104,000 for four years. Just for tuition, not room, board, and books.

Include those, and the annual cost, now at about $20,000, could be about $51,000 a year, or $204,000 for the four year haul. Meanwhile, wages will not keep up.

With costs outpacing the ability to repay — and the value of the degree itself diminishing — that can only mean fewer choices for our children than we had, a prospect that is not only deeply saddening for parents, but alarming as a nation that once called itself the “land of opportunity.”

The reason for the skyrocketing costs? The student loan program.

Creating artificial demand for something, in this case college, drives costs to the moon. The same thing happened recently with housing. The Freddie Mac Home Price Index from 1976-2006 grew at an average annual rate of 6.17 percent, again outpacing incomes. Unlimited financing boosted demand and sent prices spiraling upward.

But that’s not stopping politicians in Washington, D.C. from doubling down. In fact, this week, the Senate is debating an expansion of the student loan program.

That is largely the story of the financial crisis, wherein credit, and thus asset prices, grew faster than the ability of households, financial institutions, and everybody else to repay the principal. All the while, policy makers sought ways to further blow up the bubble.

Now, we see deleveraging across the board after the bubble popped, but one area where this has not happened, yet, is in student loan debt.

The reason is because the near limitless federal financing remains in place, because default is impossible, and because unlike housing, there is no private market feedback at financial institutions despite an extremely high delinquency rate on student loans.

The fact is, minus these loan programs, college would much cheaper, and housing would be more affordable.

Sure, fewer people would go on to obtain college degrees without the financing. But, in an alternate universe, markets could have handled post-secondary school education and training without the debt. Institutions would find other ways to offer economically viable skills that could be paid for out of pocket or through increased savings.

Another benefit of ending the program is that costs for those who actually do need to go to school for the skills that were acquired would be kept under control. This would have net benefits throughout the economy. The cost of a medical degree being cheaper would lead to lower health care costs, for instance.

Instead, what we’re doing is leading directly to a higher cost of labor for U.S. employees. So, if you’re a computer programmer, an American, with $50,000 of student loan debt, and you’re competing against someone from India with zero student loan debt, who’s more able to compete on cost?

Even so, that’s not stopping students from continuing to go to school, with the National Center for Education Statistics projecting college enrollment to increase 14 percent to 24 million by 2022.

It’s called a perverse incentive for a reason. If you want to get ahead, economically speaking, based on labor statistics, you’re better off going to college with comparatively lower unemployment rates. And if you want to afford college nowadays, you’ll be hard-pressed to do so without taking on the debt.

But, watch out, even if you go through all of the trouble, as the years go on, it will become even more difficult to compete in the current global environment. It’s simultaneously a catch 22 and a cycle of diminishing returns.

Ostensibly, in the cases of housing and education, the purpose of all this federal credit allocation is to achieve social ends. But, over time the negatives have begun to outweigh the positives. We’re seeing very bad outcomes for millions of people who are taking on the debt. It’s a policy issue that we’ve gotten horribly wrong in the past 30 years.

Without federal credit driven education and housing — we might find that a similar standard of living could be sustained at far lower, nominal wages.

In the very least, loans could be allocated based on an ability to repay given chosen fields of study. People would adjust their behavior accordingly, and only go to school for professions that actively require degrees. Institutions would adjust their prices. The truth is, there is zero risk calculus in making student loans. That has to change.

Instead, we’re becoming poorer with all of this debt, going broke paying a highly inflated premium for things those who truly need it could pay for themselves. We may be more educated as a nation, but we sure are dumb.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.